Originally published by The Los Angeles Times:

An event like yesterday’s slaughter of at least 10 staff members, including four political cartoonists, and two policemen, at the office of Charlie Hebdo newspaper in Paris, elicits so many responses that it’s hard to sort them out.

If you have a personal connection, that comes first.

I do.

I met a group of Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, including one of the victims, a few years ago at the annual cartoon Festival in Angoulême, France, the biggest gathering of cartoonists and their fans in the world. They had sought me out, partly as fans of my work – for whatever reason, my stuff seems to travel well overseas – and because I was an American cartoonist who speaks French. We did what cartoonists do: we got drunk, complained about our editors, exchanged trade secrets including pay rates.

If I lived in France, that’s where I’d want to work.

My French counterparts struck me as more self-confident and cockier than the average cartoonist. Unlike at the older, venerable Le Canard Enchainée, cartoons are the centerpiece of Charlie Hebdo, not prose. The paper has suffered financial troubles over the years, yet somehow the French continued to keep it afloat because they love comics.

Here’s how much France values graphic satire:

- More full-time staff political cartoonists were killed in Paris yesterday than are employed at newspapers in the states of California, Texas and New York combined.

- More full-time staff cartoonists were killed in Paris yesterday than work at all American magazines and websites combined.

The Charlie Hebdo artists knew they were working at a place that not only allows them to push the envelope, but encourages it. Hell, they didn’t even tone things down after their office got bombed.

They weren’t paid much, but they were having fun. The last time that I met print journalists as punk rock as those guys, they were at the old Spy magazine.

They would definitely want that attitude to outlive them.

Next comes the “there but for the grace of God” reaction.

Every political cartoonist receives threats. After 9/11 especially, people promised to blow me up with a bomb, slit the throats of every member of my family, rape me, and deprive me of a livelihood by organizing sketchy boycott campaigns. (That last one almost worked.)

The most chilling came from a New York police officer, a sergeant, who was so careless and/or unconcerned about getting in trouble that his caller ID popped up.

Who was I going to call to complain? The cops?

As far as I know, no editorial cartoonist has been murdered in response to the content of his or her work in the United States, but there’s a first time for everything. Political cartoonists have been killed and brutally beaten in other countries. Here in the United States, the murder of an outspoken radio talkshow host reminds us that political murder isn’t something that only takes place somewhere else.

Every political cartoonist takes a risk to exercise freedom expression.

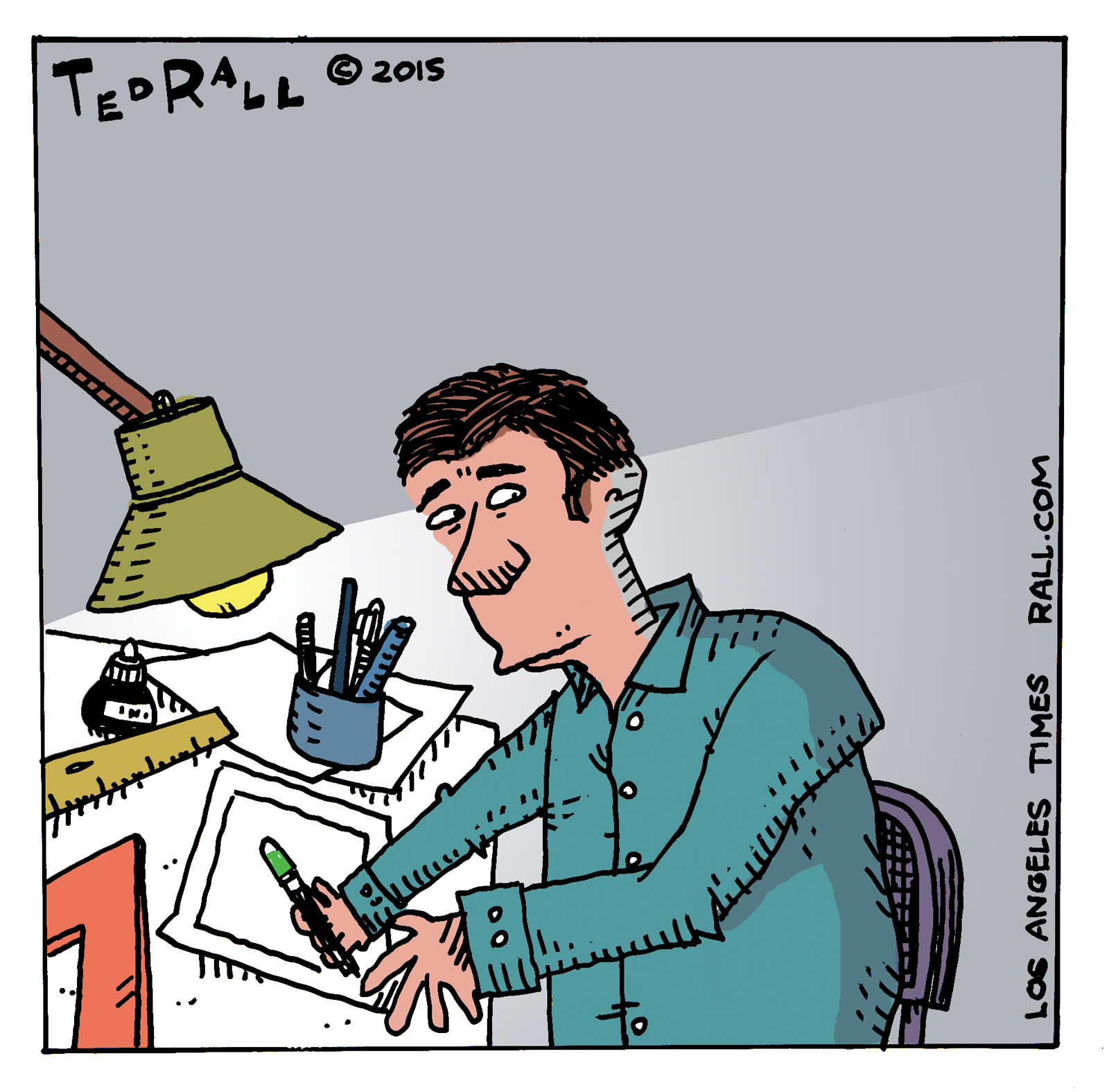

We know that our work, strident and opinionated, makes a lot of people very angry, and that we live in a country where a lot of people have a lot of guns. Whether you work in a newspaper office guarded by a minimum wage security guard or, as is increasingly the norm, in your own home, you are always one pull of a trigger away from death when you hit “send” to fire off your cartoon to your syndicate, blog or publication.

Which brings me to my big-picture reaction to yesterday’s horror:

Cartoons are incredibly powerful.

Not to denigrate writing (especially since I do a lot of it myself), but cartoons elicit far more response from readers, both positive and negative, than prose. Websites that run cartoons, especially political cartoons, are consistently amazed at how much more traffic they generate than words. I have twice been fired by newspapers because my cartoons were too widely read — editors worried that they were overshadowing their other content.

Scholars and analysts of the form have tried to articulate exactly what it is about comics that make them so effective at drawing an emotional response, but I think it’s the fact that such a deceptively simple art form can pack such a wallop. Particularly in the political cartoon format, nothing more than workaday artistic chops and a few snide sentences can be enough to cause a reader to question his long-held political beliefs, national loyalties, even his faith in God.

That drives some people nuts.

Think of the rage behind the gunmen who invaded Charlie Hebdo’s office yesterday, and that of the men who ordered them to do so. It’s too early to say for sure, but it’s a fair guess that they were radical Islamists. I’d like to ask them: how weak is your faith, how lame a Muslim must you be, to allow yourself to be reduced to the murder of innocents, over ink on paper colorized in Photoshop? In a sense, they were victims of cartoon derangement syndrome, the same affliction that led to the burning of embassies over the Danish Mohammed cartoons, the repeated outrage over The New Yorker’s insipid yet controversial covers, and that NYPD sergeant in Brooklyn who called me after he read my cartoon criticizing the invasion of Iraq.

Political cartooning in the United States gets no respect. I was thinking about that this morning when I heard NPR’s Eleanor Beardsley call Charlie Hebdo “gross” and “in poor taste.” (I should certainly hope so! If it’s in good taste, it ain’t funny.) It was a hell of a thing to say, not to mention not true, while the bodies of dead journalists were still warm. But these were cartoonists, and therefore unworthy of the same level of decorum that a similar event at, say, The Onion – which mainly runs words – would merit.

But no matter. Political cartooning may not pay well, or often at all, and media elites can ignore it all they want. (Hey book critics: graphic novels exist!) But it matters.

Almost enough to die for.