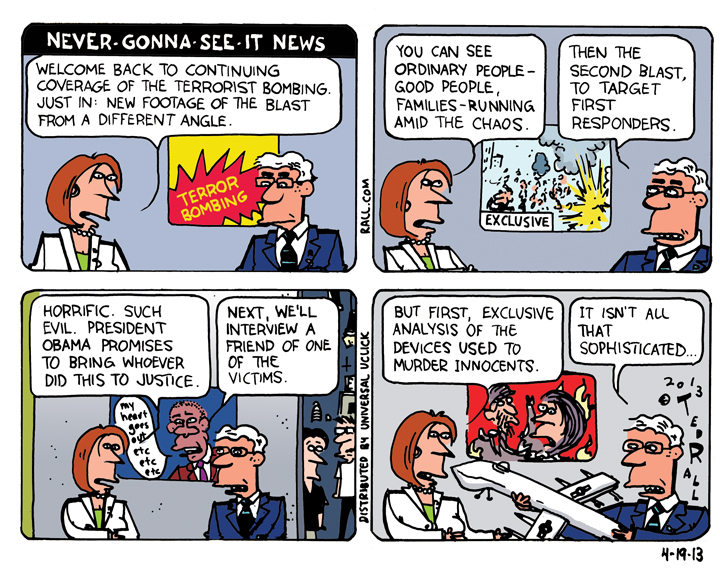

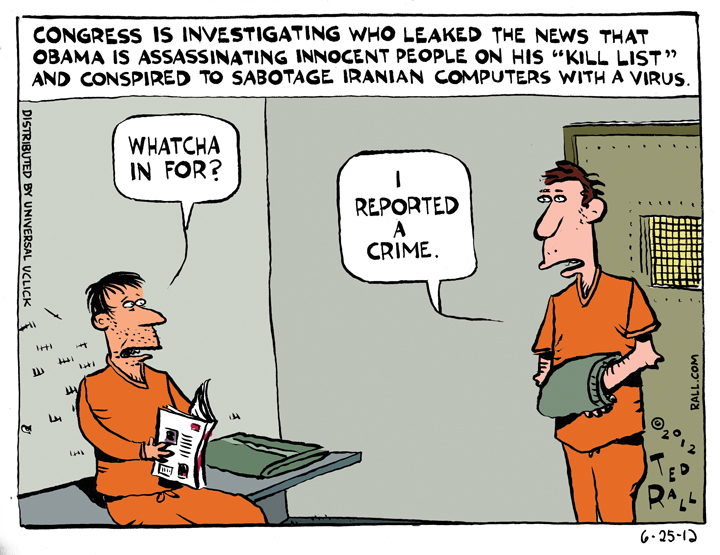

As his colleagues shifted in their seats in awkward disgust, disgraced former Memphis Commercial Appeal editorial cartoonist Bill Day delivered a smarmy, tacky 15-minute filibuster masquerading as a defense of plagiarism.

The arena-like setting was a conference room at this year’s Association of American Editorial Cartoonists convention, held in Salt Lake City. Earlier this year, Day, a 60-year-old artist whose career spans three decades at several papers, including the Detroit News, was accused of one count of plagiarism – scraping an illustrator’s rendition of an automatic weapon from the Internet, removing his signature and copyright information, adding words and additional artwork, and presenting it as his own without the customary attribution or permission from the original artist. (He claimed that he pulled the cartoon after being made aware that there was a problem, and that no newspapers ran it. In fact, it went out to hundreds of papers.) Even more serious in the jaundiced eyes of cartoonists attending the convention this year, a Tumblr blog collected at least 160 discrete sets of repurposed cartoons drawn by Day himself, totaling nearly 1000 pieces. In these recycled, or “self-plagiarized” cases, Day created a “new” cartoon by altering a few details of a previous work and issuing it as new.

Barely behind the scenes in all this was Daryl Cagle, formerly a cartoonist for the Honolulu Star Bulletin, and now sort of an Arianna Huffington of comics aggregation and syndication. Cagle distributes Day’s work. When the scandal broke, rather than fire Day – something that I had to do to two of my colleagues when I was a syndicate executive – Cagle vigorously defended his actions, bragging that he was “amused” and did the same thing himself, and encouraged other cartoonists to follow their example as a way to cut corners and meet deadlines. Said encouragement took the form of posts to Cagle’s influential blog, keeping Day on board the syndicate, dissembling on his behalf, doing even more outrageous things himself, and organizing an Indiegogo fundraising campaign on Day’s behalf – the only such campaign conducted on behalf of any editorial cartoonist on Cagle’s roster – that raised $42,000 from fans and sympathetic readers who believed Cagle’s videotaped plea that one of America’s best editorial cartoonists was in danger of becoming homeless. (I was one of them. I contributed $100.)

Despite Cagle’s best efforts to muddy the waters and rally his own cartoonists, many cartoonists disapproved of what Day had done, and more so of his brazen, unrepentant attitude. Two days before the convention, in fact, he sent out yet another cartoon – an obit cartoon of the not-dead-yet Nelson Mandela – that appears to have been repurposed.

Plagiarism, conflict of interest, cartoon repurposing and other ethical violations have been a long-standing problem in the field. When I was president of the Association between 2008 and 2009, I managed to push through the first ethics-related bylaw in the 50-year history of the Association: a proviso that permits the Board of Directors to expel a member it determines to have committed plagiarism. This didn’t go far enough: it didn’t cover nonmembers like Day, for example. But it was a start.

Many cartoonists seemed to believe that calling out fellow artists for ethical lapses would turn us into a sort of “cartoon police,” ultimately resulting in internecine conflict that would terror us apart. Some of us, mainly me and my friend Matt Bors, replied that bad behavior by a few members of a profession is a bigger threat, since it tarnishes the entire field by association, especially when the main professional Association of that field remain silent, and thus guilty of tacit consent.

This year’s convention organizers decided to address the issue by holding a town hall forum on plagiarism, recycling, etc. with the centerpiece being a proposed AAEC Code of Ethics drafted by myself and Bors. Our proposal spans a full range of lapses, from brazen plagiarism – tracing and Photoshopping other people’s work, through the kind of thing that Bill Day does, all the way to stealing other people’s ideas and jokes.

A few weeks before the convention, Bill Day expressed an interest in attending in order to defend himself. He believed himself completely guiltless and thought that most of us would come around to his way of thinking if we heard from him in person. It should be noted that he had already published at least two blog entries in which he accused the Association of being composed of a pit of snakes – he literally drew this – and attributed his actions to a busy schedule holding down multiple jobs while trying to support his family. Oh, and not to be forgotten: he also blamed the death of his brother and even his – I swear this is true – his cat. He didn’t make a direct link saying that he had plagiarized and recycled due to these events, or even because he was simply too busy to do good original work, but the line of argument was clear to all.

I didn’t think it was a good idea for him to come to the convention. And I will also confess to being more than a little frightened. He lives in Tennessee, a state with liberal gun laws. And I was by far his most strident critic.

In the event, he requested time to speak on the first day of the convention, Thursday. But when the scheduled time rolled around, he was nowhere to be found. He told the incoming president that the crowd wasn’t big enough. However, everyone was there. What did he want us to do, get people off the street? He rescheduled for Friday. It was supposed to take place over breakfast, but instead of Day pleading his case, there he was, chowing down on our food – food he didn’t even pay for, since he wasn’t registered for the convention and isn’t a member anymore. Again, he wimped out.

Annoyed, I hit the social networks, letting the world know that this manipulative plagiarist had wussed out not once, but twice, distracting us from important business and wasting everyone’s time. I heard from several colleagues, urging me to take down my posts lest the supposedly emotionally unstable Day finally be pushed over the edge and commit suicide. Apparently, the night before at a local bar, he had been talking about offing himself. I replied that, since it is evident that he doesn’t usually do what he says, there was nothing to worry about.

At this writing, he is still alive and still spending his $42,000.

Finally, on Saturday morning, Bill decided to grace the microphone with his presence. Following an engaging presentation on the history of editorial cartoon plagiarism in the United States by Joe Wos – did you know that the famous Paul Revere cartoon of the Boston massacre was brazenly plagiarized, and that he was called out and pretty much threatened with a duel over it? – and an overview of the proposed code of ethics, Bill took the stage. Incoming president Mark Fiore warned him that he would be limited to a strict 15 minutes, as we were getting started late and we had not planned for him to speak at this time. Everyone was quiet and respectful. No rolling eyes. We just sat and watched.

It was an epic act of self-immolation.

For 13 minutes, Bill Day revisited how he first got into cartooning. About his childhood in the segregated Deep South, how a friend was murdered in a racial bias incident. Then he seemed to get obsessed over accusations that his plagiarism stemmed from laziness. “They call me the lazy cartoonist,” he kept saying. He talked about how he waited until the age of 34 to land his first staff cartooning job, apparently something he still feels bitter about. (I turn 50 this year, and have never gotten one.) He held up a photograph of a box-sorting facility where he had worked in Memphis, for FedEx, and bitterly complained about here he was, at age 60, sorting boxes rather than drawing cartoons. (Many of the cartoonists in the room have performed manual labor, including yours truly.) He pointed out that he volunteers, reading to children in underprivileged areas, and held up a photograph of himself with African-American children. You could almost hear an audible gasp of disgust from the audience at this I-have-black-friends gambit. Not to mention, if he’s too busy to draw original work, why does he have time to volunteer anywhere? He didn’t say it, but the implication was clear – struggling to make ends meet after getting laid off by the Commercial Appeal prompted him to cut corners as a cartoonist. But if that was the case, why not just apologize and promise not to do it again? Especially now that he has a cool $42,000 to live off of for at least the next year?

As I watched Day ramble, I kept thinking that I could have gotten him off the hook in three minutes flat. All he needed to say was that other cartoonists, like John Sherffius, have used copyrighted and trademarked material as important components of their cartoons, and that he didn’t know it was wrong to do so. That he only did it once. That he wouldn’t do it again. And that if any royalties came in, if the cartoon ran anywhere, he would send them to the original copyright holder. As for the repurposed cartoons, he could have said – quite credibly – that he wasn’t the only guy who did this sort of thing. (Mike Ramirez comes to mind.) That it’s his work to recopy, he owns the copyrights. That you can’t punish someone retroactively. If the association decides to enact a rule against this sort of behavior going forward, he would abide by it, but until then, he was guilty of nothing more than cutting corners. Frankly, that would have done the job. But he couldn’t. Like the telltale heart in the Edgar Allen Poe story, his guilty conscience wouldn’t let him. He knew he was corrupt. So he had to make lame excuses.

He brought up his dead brother. And his dead cat. Again.

By the way, it turns out that it wasn’t a dead brother at all. I found out that afternoon that it was really a cousin. I bet he didn’t have a cat either.

Finally, at Minute 13, he began to address the issue of the plagiarized cartoon. But he talked so slowly that, even though Mark Fiore let him run on an extra five minutes, he didn’t get anywhere. The issue remained as opaque, and undefended, as ever. It was hard to watch: sad, infuriating, and ultimately the very definition of pathetic.

Bill left the room so that we could consider the code of ethics.

Mostly, cartoonists expressed the usual doubts. In particular, they were concerned about the strong enforcement provisions that I had included, directing the Association, when it becomes aware of ethical misbehavior, to issue public statements about them and to notify employers. Paul Fell said that we were in danger of fighting while we were rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, and in the end there might only be three of us left. Patrick Henry-like, I exclaimed, “Better three with integrity than 300 without!”

Some anti-Code cartoonists pointed out that there’s a gray area when it comes to defining plagiarism. Bors countered this by saying that that shouldn’t be an excuse to throw up our hands and not take any action at all.

Steve Kelley, until recently the cartoonist for the New Orleans Times Picayune and now the co-creator of “Dustin,” conceded that ethics has become a serious issue yet characteristically called for a free market solution: with the Internet, he said, you can always count on a blogger to reveal these things, and then the cartoonist in question is shamed and loses his job. I think that this is when the vibe in the room started to shift. “Look at Bill Day!” I said. “He’s a plagiarist. His employer enables him. In fact, thanks to his employer, who also recycles cartoons without letting editors know, he got a $42,000 raise – the biggest raise in American editorial cartooning! No one else in this room got a raise like that. Hell, many people in this room don’t even make that much.”

One of the big problems has been that cartoonists guilty of plagiarism have worked for years for newspapers and syndicates that remained unaware of their actions. So In extreme cases, I think it’s important for the Association to inform them. We can’t fire anyone, nor should we want to, but if an employer wants to keep a plagiarist on board – like Daryl Cagle is currently doing – they should make that decision with their eyes open. I drew an analogy with the American Medical Association, that if the AMA became aware that one of their members, or any doctor, is a quack, his patients and employers have the right to know. Otherwise, we would be complicit. This is not without precedent. Past presidents of the Association have notified cartoonists’ employers.

It would be no small stretch to say that Matt Bors and I were the only two people in the room arguing in favor of putting the Code of Ethics on a ballot for consideration by the membership. And yet we carried the argument. Although it felt lonely at the time, I have to say that there is no better place to be than in a group of friends and colleagues who respect you enough to change their minds if you are able to make a strong argument against their previously long-held convictions. I am grateful for their open-mindedness and willingness to listen.

As we prepared for this vote, Daryl Cagle moved that all discussion cease. That we never discuss the topic of ethics at all. That we not vote on whether or not to have such a code. That we not vote on whether or not to put a code on the ballot for the membership to consider. That we just simply stop talking about it. “This will destroy the Association. All this backstabbing,” he said, visibly furious. If English has any meaning, of course, this is the very opposite of backstabbing. This is all out in the open. Outgoing president Matt Wuerker, presiding over the business meeting, asked if there was a second to Daryl’s motion. There wasn’t. Crickets. Not even his syndicate cartoonists were willing to contribute to such a brazenly anti-democratic attempt to squash the discussion. And so, the ballot goes out to the nation’s editorial cartoonists later this year. They will get to decide whether plagiarism, recycling, conflicts of interest and the like should be something that the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists take a public stance against.

Every other journalistic organization does.