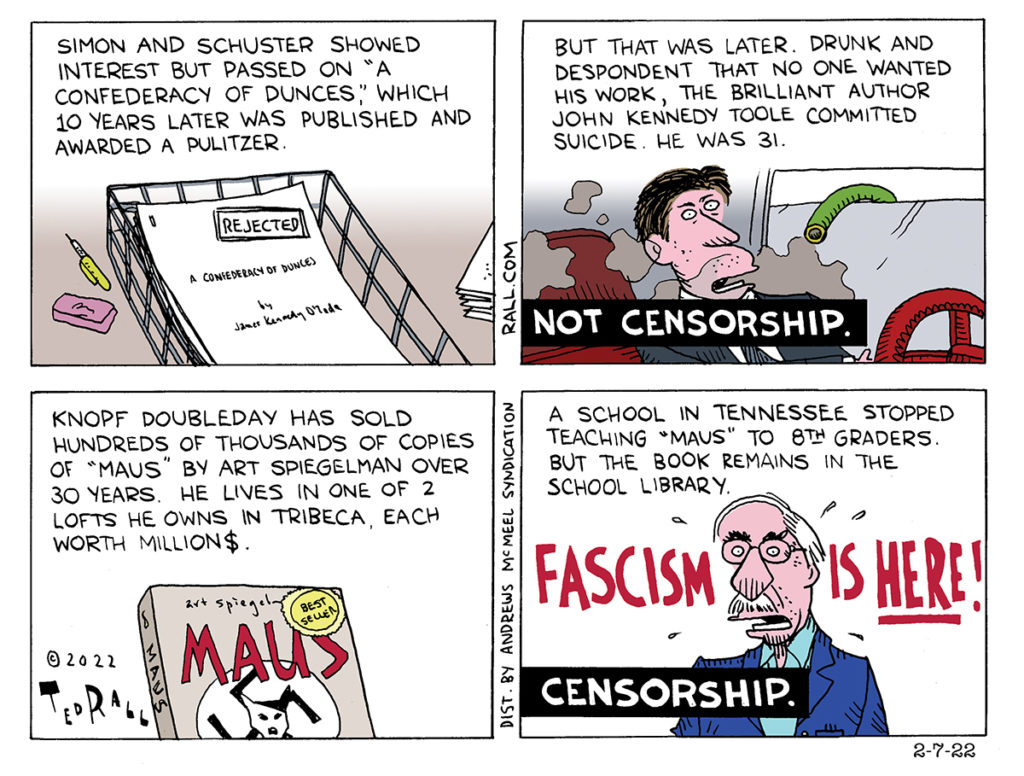

The decision of a Tennessee school board to remove a graphic novel about the Holocaust from the eighth grade curriculum has many people crying censorship. But what really is censorship? Why do we not consider economic censorship, the decision not to print something in the first place, less severe than something like this Tennessee decision? Better, after all, to have been printed and sold than to have never been printed and sold.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Our Politicians Need an Education

Why Both Democrats and Republicans Miss the Big Picture

Public education is mirroring American society overall: a tiny island of haves surrounded by a vast ocean of have-nots.

For worried parents and students, the good news is that spending on public education has become a campaign issue. Mitt Romney is pushing a warmed-over version of the old GOP school voucher scheme, “school choice.” The trouble with vouchers, experts say (and common sense supports), is that allowing parents to vote with their feet by withdrawing their kids from “failing schools” deprives cash-starved schools of more funds, leading to a death cycle—a “winner takes all” sweepstakes that widens the gap between the best and worst schools. Critics—liberals and libertarians—also dislike vouchers because they allow the transfer of public tax dollars into the coffers of private schools, many of which have religious, non-secular curricula unaccountable to regulators.

Romney recently attacked President Obama: “He says we need more firemen, more policemen, more teachers. Did he not get the message of [the failed recall of the union-busting governor of] Wisconsin?”

“I would suggest [Romney is] living on a different planet if he thinks that’s a prescription for a better planet,” shot back Obama strategist David Axelrod.

Both parties are missing the mark, the Republicans more than the Democrats. Republicans want to gut public schools by slashing budgets that will lead to bigger class sizes, which will reduce the individual attention dedicated to teaching each student. Democrats rightly oppose educational austerity, but are running a lame defense rather than aggressively promoting positive ideas to improve the system. Both parties are too interested in weakening unions and grading teacher performance with endless tests, and not enough in raising salaries so teaching attracts the brightest college graduates. Not even the Democrats are calling for big spending increases on education.

Is the system really in crisis? Yes, said respondents to a 2011 Gallup-Phi Delta Kappa poll, which found that only 22 percent approved of the state of public education in the U.S. The number one problem? Not enough funding, say voters.

Millions of parents whose opinion of their local public system is so dim that they spend tens of thousands of dollars a year on private school tuition and—in competitive cities like New York City, force their kids to endure a grueling application process.

According to one of the world’s leading experts on comparing public school systems, Andreas Schleicher of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. is falling rapidly behind other countries. In Canada, he told a 2010 Congressional inquiry, an average 15-year-old ahead is a full year ahead his or her American counterpart. The U.S. high-school completion rate is ranked 25th out of the 30 OECD countries.

The elephant in the room, the idea neither party is willing to consider, is to replace localized control of education—funding, administration and curricula—with centralized federal control, as is common in Europe and around the world.

“America’s system of standards, curriculums and testing controlled by states and local districts with a heavy overlay of federal rules is a ‘quite unique’ mix of decentralization and central control,” The New York Times paraphrased Schleicher’s testimony. “More successful nations, he said, maintain central control over standards and curriculum, but give local schools more freedom from regulation, he said.”

Why run public schools out of Washington? The advantages are obvious. When schools in rich districts get the same resource allocation per student as those in poor ones, influential voters among the upper and middle classes tend to push for increased spending of education. Centralized control also eliminates embarrassing situations like when the Kansas School Board eliminated teaching evolution in its schools, effectively reducing standards.

A streamlined curriculum creates smarter students. It’s easier for Americans, who live in a highly mobile society, to transfer their children midyear from school to school, when a school in Peoria teaches the same math lesson the same week as one in Honolulu. Many students, especially among the working poor, suffer lower grades due to transiency.

Of course, true education reform would need to abolish the ability of wealthier parents to opt out of the public school system. That means banning private education and the “separate but equal” class segregation we see today, particularly in big cities, and integrating the 5.3 million kids (just under 10 percent of the total) in private primary and secondary schools into their local public systems. Decades after forced bussing, many students attend schools as racially separated as those of the Jim Crow era. The New York Times found that 650 out of New York’s 1700 public schools have student bodies composed at least 70 percent of one race—this in a city with extremely diverse demographics.

If we’re to live in a true democracy, all of our kids have to attend the same schools.

(Ted Rall’s new book is “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt.” His website is tedrall.com. This column originally appeared at MSNBC.com)

(C) 2012 TED RALL, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.