Serendipity plays such a starring role in our lives that we never stop to ask ourselves whether we ought to accept it. A random event, especially one that turns out to be your “big break,” becomes a charming story—even though, really, such happenstance is an indictment of a system that is no system at all.

Serendipity plays such a starring role in our lives that we never stop to ask ourselves whether we ought to accept it. A random event, especially one that turns out to be your “big break,” becomes a charming story—even though, really, such happenstance is an indictment of a system that is no system at all.

Donald Sutherland, the New York Times noted in his recent obituary, “first came to the attention of many moviegoers as one of the Army misfits and sociopaths in ‘The Dirty Dozen’ (1967), set during World War II. His character had almost no lines until he was told to take over from another actor. ‘You with the big ears—you do it!’ he recalled the director, Robert Aldrich, yelling at him. ‘He didn’t even know my name.’”

Wait—if the other guy hadn’t messed up, we’d never have gotten to know this brilliant actor?

James Kent, a chef and restauranteur who died June 16th at the age of 45, launched his career in a similarly random way, according to the Times: “In 1993, when Mr. Kent was a 14-year-old growing up in Greenwich Village and already working at a restaurant, his mother made him knock on the door of their building’s newest resident, the celebrity chef David Bouley. The young man asked if he could spend time in Mr. Bouley’s kitchen. Mr. Bouley said yes. James spent the summer working at Bouley, the chef’s TriBeCa mainstay. Before long, he was also working at famed New York City restaurants like Babbo, Jean-Georges, Eleven Madison Park and NoMad, where he became the executive chef.” If his mom had been shy, what would have become of him?

Random twists have defined my career too. Looking to pass the time after I missed a bus, I came across an early alt-weekly newspaper on the bench and decided to send a few copies to its editor, who became my first client. While visiting the president of my newspaper syndication company, he took a call from a chain of radio stations looking for on-air talent that ultimately hired me. A quarter century later, I still do talk radio.

These stories are spookier than they are cute. If I’d caught that bus, I might have given up on cartooning and stuck to banking. If I’d gone to the syndicate office in Kansas City a week sooner or later, I probably would have missed that opportunity. And I’m good at radio.

Leaving employment—the activity to which we spend most of our lives—totally to chance is insane.

The job market excepted, every major economic activity is governed by constantly evolving attempts to rationalize it toward higher efficiency and increased output produced by smart imaginative people who study detailed data and deploy sophisticated technology like computer algorithms to make the most of that information. Advertisers and marketers collect everything about everyone to assess how to promote goods and services. Defense contractors consistently improve the efficiency of their killing machines while taking care not to create or expand so many conflicts that they significantly reduce their customer base. Retailers and shippers track every part of every product from conception to manufacture to assembly to distribution to sale, and beyond into recycling and reuse, ceaselessly searching for ways to reduce labor and the cost of goods. Bankers and speculators squeeze every last basis point out of every dollar, ideally borrowed below cost, developing innovative financial products with one goal in mind: increasing profits.

All of this capitalistic activity begins with basic employment. Bosses pay workers, workers create added value on the job. Salaries drive our consumer-based economy.

Human potential is the foundation of the system—yet there isn’t the slightest attempt to maximize it so that society extracts as much productivity as it can from as many employees as it can. Corporations call their personnel offices “human resources” while they squander those same assets.

State-run socialist economies like the Soviet Union and China under Mao deployed thorough occupational and aptitude testing regimens on their populations beginning in infancy. School coaches were trained to act as talent scouts, identifying athletes with potential early so they could be funneled into state-run institutions dedicated to building world-class teams of athletes tasked with making their countries proud in international competitions. Students with a knack for STEM were diverted into challenging curricula designed to pump out the world’s finest scientists. Whether a brilliant cyclist or poet or dancer or administrator was from a rich family in Moscow or a poor one from the Urals, there was a good chance their skills would come to the attention of authorities who could find a way to cultivate their abilities.

The socialist system was far from perfect. Being good at a subject doesn’t mean you want to spend your life dedicated to working on it; I was an excellent math student but my professors’ suggestion that I become a mathematician made me want to die. Occupational interest surveys are inherently subjective and less than perfectly reliable. Still, the one I took in junior high school (when the U.S. was influenced by its competition with the USSR) that found I would be best suited as a lawyer—and least suited to sorting tobacco leaves by size and color—was not far off the mark. I do love the law. Though the solution may not be easy, the problem is undeniable: the U.S. has millions of people, young and old, whose remarkable talents in a field go to waste—and not because those citizens aren’t interested in exploiting them.

America wastes its geniuses. Great would-be novelists are pumping gas. Awesome should-be coders are serving coffee. Fantastic engineers are running themselves ragged in Amazon warehouses. At most, an American only works an average of 50 years. Compassion, humanism and macroeconomic national interest calls for an employment market that makes those five decades as satisfying and fulfilling as possible for as many people as possible.

This syndicated column by a professional writer was authored by a guy who, as a young man, could often not find work at all, or got stuck as a dishwasher and telemarketer who also drove a cab. One of my colleagues at the telemarketing firm is now a wildly successful ad exec. These transformations are not stories of a system succeeding—they are individuals surviving and subsisting and blossoming despite a system devoid of mechanisms to identify, say, workers with a knack for advertising and writing and training them to get better so they can be funneled into positions where they can do their best for themselves and their country.

Even as those with potential sink into depression and opioid addiction, the sub-par are elevated to positions they do not deserve and in which they cannot excel. So we have U.S. Senators who do not understand history or geopolitics; many do not even use the Internet they’re trying to regulate. Companies put CEOs in charge of enterprises they shouldn’t even part of, much less running into the ground.

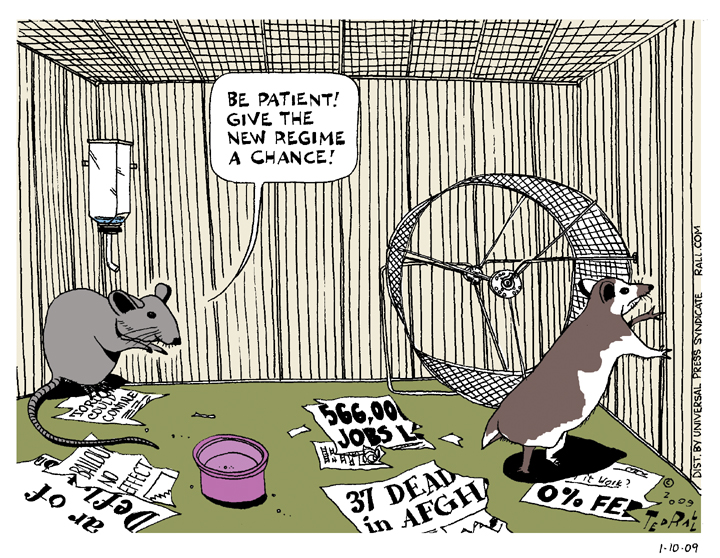

There’s got to be a better way. But who’ll think of it? Not the idiots in charge.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. His latest book, brand-new right now, is the graphic novel 2024: Revisited.)