Here’s what you need to understand the state of political cartooning in the United States:

After the massacre of four cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo last week, 25 remain on staff at the French publication, whose circulation ranges between 30,000 and 60,000 per week.

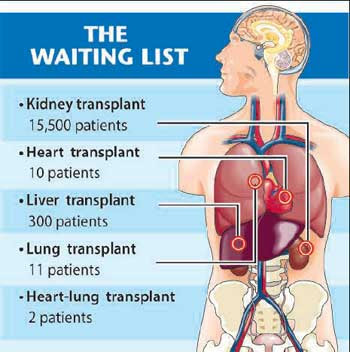

In the United States, a total of 25 staff political cartoonists are employed by the nation’s 1,350 newspapers, which have a combined circulation of 44,000,000 daily in print, plus 113,000,000 unique online visitors.

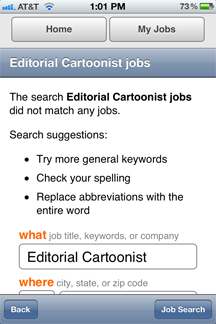

The total number of political cartoonists employed on staff by all American websites is one.

The total number at all magazines is zero.

It wasn’t always like this. According to a report issued by the Herblock Foundation, there were 2,000 political cartoonists on staff at newspapers a century ago.

Sure, print media has had to cut back due to a half-century of declining circulation. Writers, photographers and others have all suffered. But cartoonists have been eliminated at the highest rate of any journalism category by far: 99%.

New online media outlets like the Huffington Post, Salon, Slate, Vox, Yahoo News and The Intercept have hired hundreds of journalists — yet no political cartoonists.

There are more political cartoonists working in Iran and China than here.

Why has the U.S. become such a satirical desert?

In candid moments, editors confess that they’re afraid. They’re scared of angry emails from readers. (Prose doesn’t elicit as much reaction.) They’re worried their boss’ country-club buddies will complain about a cartoon. They’re terrified that a major advertiser might cancel its account. Narrowing profit margins and post-9/11 conservatism have amplified editorial cowardice.

When cartoons make the headlines, like last week, it’s another story.

News outlets couldn’t get enough political cartoons post-Charlie, noted Tjeerd Royaards, editor of the Dutch cartoon web magazine Cartoon Movement. (Disclosure: Cartoon Movement has published my work.) But they wanted it all for free: “the majority of media website[s] simply embedded the cartoons from the[ir] Twitter feed[s], foregoing the courtesy of asking the artists for permission to show their work, let alone pay for it.”

Royaards continued: “Although the media certainly seemed to wholeheartedly support cartoonists in the wake of the [Charlie Hebdo] attack, this support proved to be dubious, and might even be considered a greater threat to political cartooning than any terrorist attack could ever hope to be.”

Writing about the state of the profession this week, my colleague the alternative political artist Mr. Fish painted an even bleaker portrait of the future:

“The significance of those [declining cartoonist job] numbers might best be understood when compared to the dwindling numbers of an endangered species, not unlike the polar bear, who draws worldwide sympathy primarily when pictured drifting forlorn and alone on a shrinking block of ice or lying skinless and butchered by mindless thugs on a crimson bank. Likewise, it should be noted with some urgency that something systemic in the culture (similar to global warming, corporately inspired, government subsidized and willfully ignored by a disempowered public) is substantially diminishing the cartoonist population and threatening the very survival of the rendered word and the contemplative caption — and the very essence of creative dissent.”

Mr. Fish’s biological metaphor is an apt one.

Over the past few decades we have warned editors that we were in trouble. It’s worse now.

We are probably already past the tipping point after which political cartoonist extinction becomes inevitable.

One major threat is the loss of artistic diversity. In the same way that insufficient genetic diversity can cause a species to enter a death spiral — the cheetah is a famous example — American political cartooning no longer has enough practitioners to grow via cross-pollination, by being influenced by and against one another the way that I, for example, saw the work of the cartoonists Mike Peters and Pat Oliphant in the 1970s and wanted to ape the first and rebel against the latter. Most working political cartoonists in the U.S. are over age 55. So many have been laid off or discouraged that, even if I were given a zillion dollars to hire all the best cartoonists left, I’d have trouble finding 10 or 20. A profession that offered a dazzling variety of styles as recently as 2000 looks increasingly cut-and-paste.

There are only two basic styles left: the older, crosshatched, donkeys-and-elephants single-panels influenced by the late Jeff MacNelly, and the wordier, multi-panel approach that emerged in alternative weeklies during the 1990s.

Getting back to the polar bear analogy, there aren’t enough “newborn cubs” — young political cartoonists in their 20s — to form the roots of the next wave of political cartoonists if and when editors gain the courage to start hiring. Aside from the fact that there’s no way for a young political cartoonist to earn a living, young adults don’t see political cartoons in the media they consume.

The top websites read by Millennials, like Vice, Upworthy and BuzzFeed, refuse to hire political cartoonists. You can’t get inspired to pursue a profession if you don’t know it exists.

What to do?

I’m hoping for greed. Nothing gets clicks like a political cartoon. At some point, some twentysomething editor at a news start-up is going to figure that out.

(Ted Rall, syndicated writer and cartoonist, is the author of the new critically-acclaimed book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan.” Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2015 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM