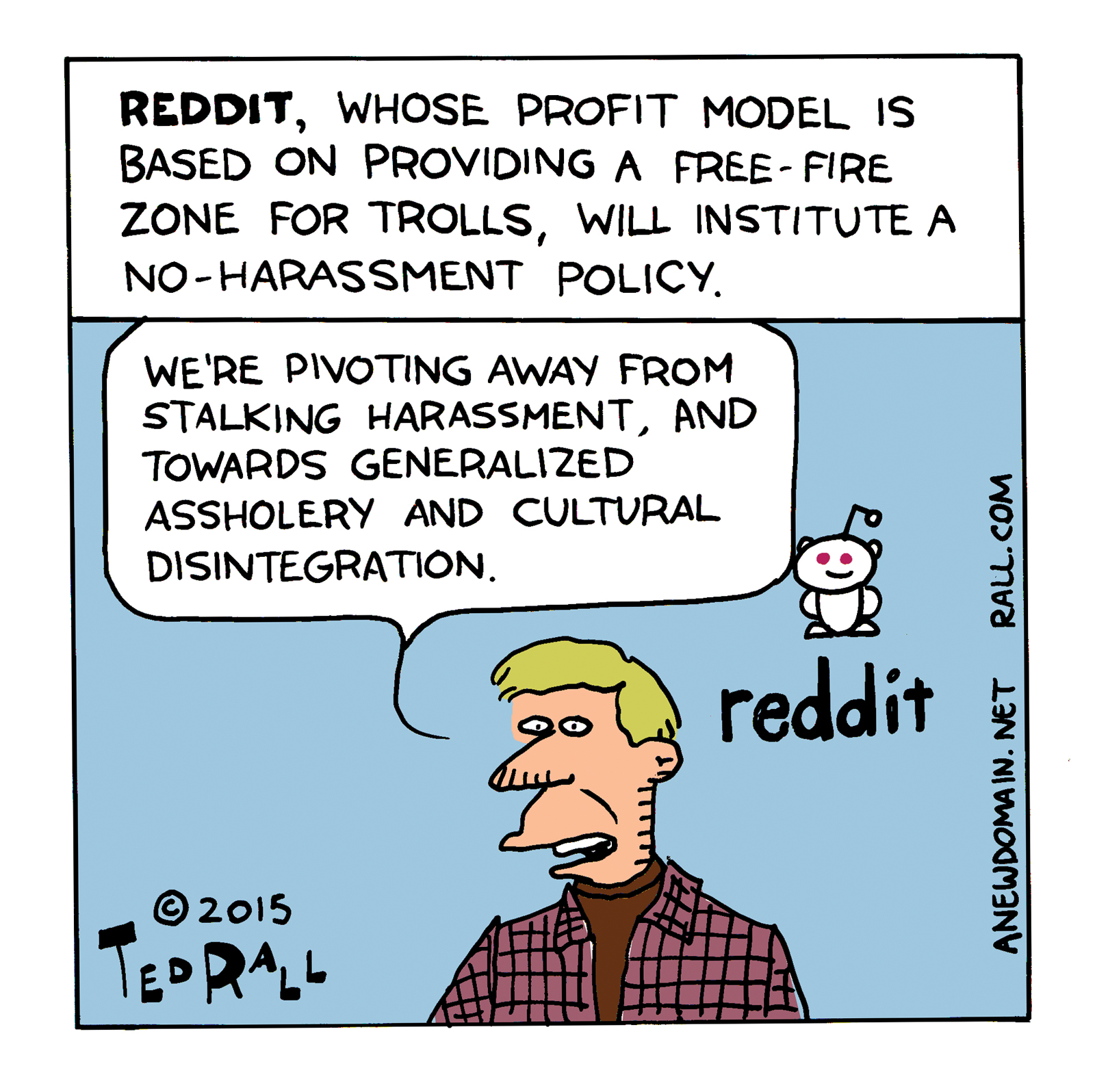

Originally published by ANewDomain.net:

Reddit, the “id” of the Internet, announces a new policy against the harassment that made it what it is today. There’s an irony behind the Reddit harrassment policy that won’t be lost on anyone who has ever had to deal with the service.