Two weeks ago I discussed some of the projects and jobs that, for whatever reason, I never got to do during my career as a cartoonist and writer. The stuff we don’t do, I wrote, defines as much as what we do. This week: my weird stuff that never came together.

Hugh Hefner died in 2017. I was un-sad.

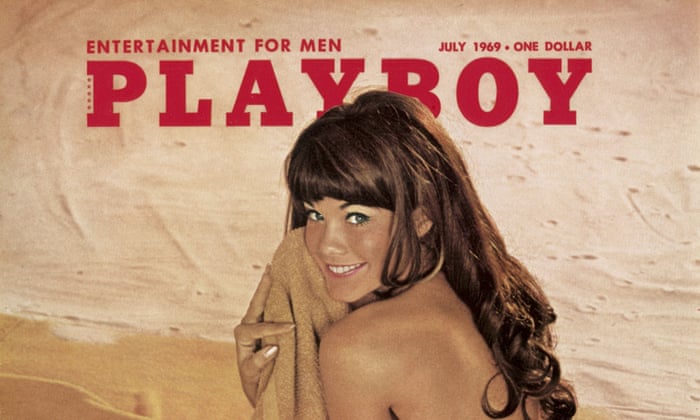

Un-sad is not happiness. It’s feeling neutral when you’re supposed to be unhappy. Hef, who as a young man wanted to be a cartoonist, had bad taste in cartoons and architecture but superb taste in art directors. In the 1990s his charismatic cartoon editor Michelle Urry recruited me to help modernize Playboy’s graphics, whose content and aesthetics were stuck in the 1960s the way The New Yorker looks like it’s still the 1920s. Under Urry’s tutelage I drew scores of sex-themed cartoons with a left-wing social and political bent. I think they were some of the funniest stuff I’ve ever done.

“I love them but Hef hates them,” Michelle told me. “He wants to leave everything the same.” So no commie sex comix. Sadly for real, Urry died prematurely.

One of my oddest aborted projects was a comic strip in which I partnered with another cartoonist to whom I will grant anonymity. Conceived over planter’s punches at a defunct Village bar called the Dew Drop Inn and marketed to alternative and underground newspapers under a pseudonym, “Lil’ Adolf and His Friend Eva” featured the antics of two kids in an American high school facing situations à la Archie and Jughead (drawn a bit like that) with a twist: neither knows they’re clones of a certain German Chancellor and his girlfriend Eva Braun. Faced with a dilemma—homework, bullying, getting picked last in gym class—the pair inevitably resorts to violence. I often decry newspaper editors as a band of boring middlebrow risk-averse Babbitts but in this case I applaud their discretion. Not one paper expressed interest in “Lil’ Adolf.” I am grateful.

My UPN fiasco left a few scars. In 1998 or 1999 Dean Valentine, head of the now-forgotten TV network that aired the “Dilbert” TV show, asked me to develop an animated series to follow “Dilbert” at 8:30 pm. Valentine had seen my cartoons in the Los Angeles Times. While the lawyers hashed out the deal I toiled over plots and character designs. The result would be a show called “Boomerang.”

Whereas “The Simpsons” is about a nuclear family in the suburbs, “Boomerang” would concern a postmodern extended tangled yarnball of relationships between half/stepsiblings and their LGBTQA partners and adopted children and pets living in a sprawling dilapidated Victorian hulk in Newark reflective of America’s splintering socioeconomic infrastructure. Very Gen X.

Six months or so into it, the deal was finalized. I signed a stack of contracts. My lawyer shoved them into a FedEx. And we never heard from UPN again. We called and called…no reply.

Ghosted by a corporation! Now it’s standard business practice. Twenty years ago, though, neither me nor my attorney had ever heard of such a thing. We could have sued for breach of (half-signed?) contract and perhaps won. But I wanted to do another show someday and didn’t want to get blackballed by Hollywood companies.

Two of my TV show pitches attracted high-level interest in Tinseltown, though not as close to those execution copies of contacts at UPN. Aside from the glory, I would have wanted to watch them. That’s my test for cartoons, books, podcasts, whatever I make. If I were a fan, would I want to consume it myself?

“Green”’s premise was simple: if the planet is in danger, if ecocidal maniacs are causing climate change, mass extinctions and possibly the end of the human race, isn’t the right thing to do to murder the bastards? “Green” the series would have been about a “deep green” terrorist organization—think Earth First! meets the Weather Underground if WU had had more members—and a FBI counterterrorist taskforce assigned to find and stop them. I saw it as a political, existential HBO-type show starring brilliant, troubled lead characters.

I scored repeat pitch meetings with Hollywood production companies and a few networks. But interest waned. Calls were no longer returned.

Shortly after the 2000 election I shopped a treatment for “The Bushies,” an animated series about the then-First Family in which all the characters were secretly different than their public personas. In “The Bushies” George W. Bush was a brilliant, soulful intellectual. Cheney was a mushy crybaby. The Bush twins were nefarious serial killers. Like many other L.A. dreams, “The Bushies” died in a major network’s “business affairs” department because some idiot lawyer worried about libel suits.

The Bushies were public figures, as public as could be. This was classic political satire, immune from litigation assuming a Bush was dumb enough to sue. Most countries (France, Germany, England, Russia) had similar comedies mocking their leaders. As usual, the in-house attorney won. Trey Parker and Matt Stone moved quickly with their “That’s My Bush!” for Comedy Central. It was not one of their finer resume entries.

Later in the decade I tried to jumpstart a political animation career with five-minute shorts. I drew and wrote; David Essman animated. We did 35 of them in all. Some still hold up, all are worth watching (the Tea Party one is great), but despite my aggressive marketing campaign I couldn’t sell them to anyone. It’s sad: static political cartooning is dead, Internet companies are obsessed with video but no one wants animated cartoons. My political cartoonist colleagues have had similar lousy results.

One of my most ambitious projects got killed by 9/11.

Less than an hour before the first plane hit the World Trade Center, my train left New York’s Penn Station for Philadelphia. By the time me and my business partner, now a magazine editor, arrived in Philly the Parks Police were shutting down the Liberty Bell. (My first post-9/11 joke: “don’t worry, it’s already broken.”)

We were in Philly to close a $1.5 million deal with a Pennsylvania media investor in Brooklyn Weekly, the alt weekly newspaper we wanted to launch in the borough. At the time Brooklyn still being hipsterized. The 19 hijackers messed it up. As we watched the events on TV the moneyman leaned back into his seat. “Deal’s off,” he announced as he wrote off the nation’s biggest city. “No one will ever do business in New York again.”

“With all due respect,” I replied with nothing-to-lose bravado, “that’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. They still do business in Hiroshima.”

Osama bin Laden may have done me a favor. Craigslist destroyed the classified ads business that were the basis of the alt-weekly profit model. The dot-com crash pushed the economy into a slump that lasted the rest of the decade. Brooklyn Weekly might have been doomed.

Or maybe not. Brooklyn is different. I could easily see a weekly with a strong political and cultural point of view succeeding now.

(Ted Rall, the cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)