The Obama Administration told a UN committee investigating torture by the US and its adherence to the Convention Against Torture (CAT) that it wants to guarantee future US torture victims no more than four hours of sleep.

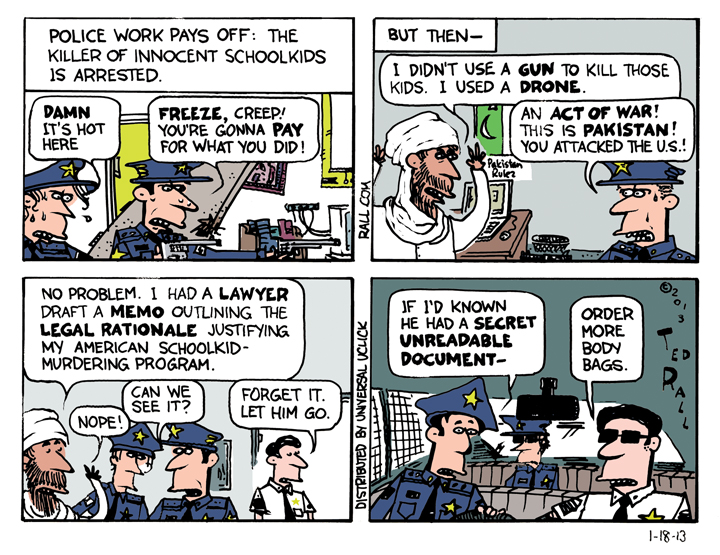

More Body Bags

After a bunch of school children are killed, American police track the killer to Pakistan. There they run into some legal problems: not only did the killer use a drone instead of an assault rifle, he had a full-fledged legal opinion drafted by a full-fledged Pakistani lawyer justifying his drone program. And he won’t let the cops read the thing. Oh well, nothing to do.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Tied to a Drowning Man

The interconnectedness of the world economy means that US economic woes will have severe effects on others.

During the Tajik Civil War of the late 1990s soldiers loyal to the central government found an ingeniously simple way to conserve bullets while massacring members of the Taliban-trained opposition movement. They tied their victims together with rope and chucked them into the Pyanj, the river that marks the border with Afghanistan. “As long as one of them couldn’t swim,” explained a survivor of that forgotten hangover of the Soviet collapse as he walked me to one of the promontories used for this act of genocide, “they all died.”

Such is the state of today’s integrated global economy.

Interdependence, liberal economists believe, furthers peace—a sort of economic mutual assured destruction. If China or the United States were to attack the other, the attacker would suffer grave consequences. But as the U.S. economy deteriorates from the Lost Decade of the 2000s through the post-2008 meltdown into what is increasingly looking like Marx’s classic crisis of late-stage capitalism, internationalization looks more like a suicide pact.

Like those Tajiks whose fates were linked by tightly-tied lengths of cheap rope, Europe, China and most of the rest of the world are bound to the United States—a nation that seems both unable to swim and unwilling to learn.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, a process that began in the 1970s and culminated with dissolution in 1991, had wide-ranging international implications. Russia became a mafia-run narco-state; millions perished of famine. Weakened Russian control of Central Asia, especially Afghanistan, set the stage for an emboldened and highly organized radical Islamist movement. Not least, it left the United States as the world’s last remaining superpower.

From an economic perspective, however, the effects were basically neutral. Coupled with its reliance on state-owned manufacturing industries to minimize dependence upon foreign trade, the USSR’s use of a closed currency ensured that other countries were not significantly impacted when the ruble went into a tailspin.

Partly due to its wild deficit spending on the gigantic military infrastructure it claimed was necessary to fight the Cold War—and then, after brief talk of a “peace dividend” during the 1990s, even more profligacy on the Global War on Terror—now the United States is, like the Soviet Union before it, staring down the barrel of economic apocalypse.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: How the US Media Marginalizes Dissent

The US media derides views outside of the mainstream as ‘un-serious’, and our democracy suffers as a result.

“Over the past few weeks, Washington has seemed dysfunctional,” conservative columnist David Brooks opined recently in The New York Times. “Public disgust [about the debt ceiling crisis] has risen to epic levels. Yet through all this, serious people—Barack Obama, John Boehner, the members of the Gang of Six—have soldiered on.”

Here’s some of what Peter Coy of Business Week magazine had to say about the same issue: “There is a comforting story about the debt ceiling that goes like this: Back in the 1990s, the U.S. was shrinking its national debt at a rapid pace. Serious people actually worried about dislocations from having too little government debt…”

Fox News, the Murdoch-owned house organ of America’s official right-wing, asserted: “No one seriously thinks that the U.S. will not honor its obligations, whatever happens with the current impasse on President Obama’s requested increase to the government’s $14.3 trillion borrowing limit.”

“Serious people.”

“No one seriously thinks.”

The American media deploys a deep and varied arsenal of rhetorical devices in order to marginalize opinions, people and organizations as “outside the mainstream” and therefore not worth listening to. For the most part the people and groups being declaimed belong to the political Left. To take one example, the Green Party—well-organized in all 50 states—is never quoted in newspapers or invited to send a representative to television programs that purport to present “both sides” of a political issue. (In the United States, “both sides” means the back-and-forth between center-right Democrats and rightist Republicans.)

Marginalization is the intentional decision to exclude a voice in order to prevent a “dangerous” opinion from gaining currency, to block a politician or movement from becoming more powerful, or both. In 2000 the media-backed consortium that sponsored the presidential debate between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Governor George W. Bush banned Green Party candidate Ralph Nader from participating. Security goons even threatened to arrest him when he showed up with a ticket and asked to be seated in the audience. Nader is a liberal consumer advocate who became famous in the U.S. for stridently advocating for safety regulations, particularly on automobiles.

AL JAZEERA COLUMN: Censorship of Civilian Casualties in the US

US mainstream media and the public’s willful ignorance is to blame for lack of knowledge about true cost of wars.

Why is it so easy for American political leaders to convince ordinary citizens to support war? How is that, after that initial enthusiasm has given away to fatigue and disgust, the reaction is mere disinterest rather than righteous rage? Even when the reasons given for taking the U.S. to war prove to have been not only wrong, but brazenly fraudulent—as in Iraq, which hadn’t possessed chemical weapons since 1991—no one is called to account.

The United States claims to be a shining beacon of democracy to the world. And many of the citizens of the world believes it. But democracy is about responsiveness and accountability—the responsiveness of political leaders to an engaged and informed electorate, which holds that leadership class accountable for its mistakes and misdeeds. How to explain Americans’ acquiescence in the face of political leaders who repeatedly lead it into illegal, geopolitically disastrous and economically devastating wars of choice?

The dynamics of U.S. public opinion have changed dramatically since the 1960s, when popular opposition to the Vietnam War coalesced into an antiestablishmentarian political and culture movement that nearly toppled the government and led to a series of sweeping social reforms whose contemporary ripples include the recent move to legalize marriage between members of the same sex.

Why the difference?

Numerous explanations have been offered for the vanishing of protesters from the streets of American cities. First and foremost, fewer people know someone who has gotten killed. The death rate for U.S. troops has fallen dramatically, from 58,000 in Vietnam to a total of 6,000 for Iraq and Afghanistan. Many point to the replacement of conscripts by volunteer soldiers, many of whom originate from the working class, which is by definition less influential. Congressman Charles Rangel, who represents the predominantly African-American neighborhood of Harlem in New York, is the chief political proponent of this theory. He has proposed legislation to restore the military draft, which ended in the 1970s, four times since 9/11. “The test for Congress, particularly for those members who support the war, is to require all who enjoy the benefits of our democracy to contribute to the defense of the country. All of America’s children should share the risk of being placed in harm’s way. The reason is that so few families have a stake in the war which is being fought by other people’s children,” Rangel said in March 2011.

War is extraordinarily costly in cash as well as in lives. By 2009 the cost of invading and occupying Iraq had exceeded $1 trillion. During the 1960s and early 1970s conservatives unmoved by the human toll in Vietnam were appalled by the cost to taxpayers. “The myth that capitalism thrives on war has never been more fallacious,” argued Time magazine on July 13, 1970. Bear in mind, Time leaned to the far right editorially. “While the Nixon Administration battles war-induced inflation, corporate profits are tumbling and unemployment runs high. Urgent civilian needs are being shunted aside to satisfy the demands of military budgets. Businessmen are virtually unanimous in their conviction that peace would be bullish, and they were generally cheered by last week’s withdrawal from Cambodia.”

AL JAZEERA ENGLISH COLUMN: Obama’s Third War

Yesterday I published my first column for Al Jazeera English. I get more space than my syndicated column (2000 words compared to the usual 800) and it’s an exciting opportunity to run alongside a lot of other writers whose work I respect.

Here it is:

Stalemate in Libya, Made in USA

Republicans in the United States Senate held a hearing to discuss the progress of what has since become the war in Libya. It was one month into the operation. Senator John McCain, the Arizona conservative who lost the 2008 presidential race to Barack Obama, grilled top U.S. generals. “So right now we are facing the prospect of a stalemate?” McCain asked General Carter Ham, chief of America’s Africa Command. “I would agree with that at present on the ground,” Ham replied.

How would the effort to depose Colonel Gaddafi conclude? “I think it does not end militarily,” Ham predicted.

That was over two months ago.

It’s a familiar ritual. Once again a military operation marketed as inexpensive, short-lived and—naturally—altruistic, is dragging on, piling up bills, with no end in sight. The scope of the mission, narrowly defined initially, has radically expanded. The Libyan stalemate is threatening to become, along with Iraq and especially Afghanistan, America’s third quagmire.

Bear in mind, of course, that the American definition of a military quagmire does not square with the one in the dictionary, namely, a conflict from which one or both parties cannot disengage. The U.S. could pull out of Libya. But it won’t. Not yet.

Indeed, President Obama would improve his chances in his upcoming reelection campaign were he to order an immediate withdrawal from all four of America’s “hot wars”: Libya, along with Afghanistan, Iraq, and now Yemen. When the U.S. and NATO warplanes began dropping bombs on Libyan government troops and military targets in March, only 47 percent of Americans approved—relatively low for the start of a military action. With U.S. voters focused on the economy in general and joblessness in particular, this jingoistic nation’s typical predilection for foreign adventurism has given way to irritation to anything that distracts from efforts to reduce unemployment. Now a mere 26 percent support the war—a figure comparable to those for the Vietnam conflict at its nadir.

For Americans “quagmire” became a term of political art after Vietnam. It refers not to a conflict that one cannot quit—indeed, the U.S. has not fought a war where its own survival was at stake since 1815—but one that cannot be won. The longer such a war drags on, with no clear conclusion at hand, the more that American national pride (and corporate profits) are at stake. Like a commuter waiting for a late bus, the more time, dead soldiers and materiel has been squandered, the harder it is to throw up one’s hands and give up. So Obama will not call off his dogs—his NATO allies—regardless of the polls. Like a gambler on a losing streak, he will keep doubling down.

U.S. ground troops in Libya? Not yet. Probably never. But don’t rule them out. Obama hasn’t.

It is shocking, even by the standards of Pentagon warfare, how quickly “mission creep” has imposed itself in Libya. Americans, at war as long as they can remember, recognize the signs: more than half the electorate believes that U.S. forces will be engaged in combat in Libya at least through 2012.

One might rightly point out: this latest American incursion into Libya began recently, in March. Isn’t it premature to worry about a quagmire?

Not necessarily.

“Like an unwelcome specter from an unhappy past, the ominous word ‘quagmire’ has begun to haunt conversations among government officials and students of foreign policy, both here and abroad,” R.W. Apple, Jr. reported in The New York Times. He was talking about Afghanistan.

Apple was prescient. He wrote his story on October 31, 2001, three weeks into what has since become the United States’ longest war.

Obama never could have convinced a war-weary public to tolerate a third war in a Muslim country had he not promoted the early bombing campaign as a humanitarian effort to protect Libya’s eastern-based rebels (recast as “civilians”) from imminent Srebrenica-esque massacre by Gaddafi’s forces. “We knew that if we waited one more day, Benghazi—a city nearly the size of Charlotte [North Carolina]—could suffer a massacre that would have reverberated across the region and stained the conscience of the world,” the President said March 28th. “It was not in our national interest to let that happen. I refused to let that happen.”

Obama promised a “limited” role for the U.S. military, which would be part of “broad coalition” to “protect civilians, stop an advancing army, prevent a massacre, and establish a no-fly zone.” There would be no attempt to drive Gaddafi out of power. “Of course, there is no question that Libya—and the world—would be better off with Gaddafi out of power,” he said. “I, along with many other world leaders, have embraced that goal, and will actively pursue it through non-military means. But broadening our military mission to include regime change would be a mistake.”

“Regime change [in Iraq],” Obama reminded, “took eight years, thousands of American and Iraqi lives, and nearly a trillion dollars. That is not something we can afford to repeat in Libya.”

The specifics were fuzzy, critics complained. How would Libya retain its territorial integrity—a stated U.S. war aim—while allowing Gaddafi to keep control of the western provinces around Tripoli?

The answer, it turned out, was essentially a replay of Bill Clinton’s bombing campaign against Serbia during the 1990s. U.S. and NATO warplanes targeted Gaddafi’s troops. Bombs degraded Libyan military infrastructure: bases, radar towers, even ships. American policymakers hoped against hope that Gaddafi’s generals would turn against him, either assassinating him in a coup or forcing the Libyan strongman into exile.

If Gaddafi had disappeared, Obama’s goal would have been achieved: easy in, easy out. With a little luck, Islamist groups such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb would have little to no influence on the incoming government to be created by the Libyan National Transitional Council. With more good fortune, the NTC could even be counted upon to sign over favorable oil concessions to American and European energy concerns.

But Gaddafi was no Milosevic. The dictator dug in his heels. This was at least in part due to NATO’s unwillingness or inability to offer him the dictator retirement plan of Swiss accounts, gym bags full of bullion, and a swanky home in the French Riviera.

Stalemate was the inevitable result of America’s one foot in, one foot out Libya war policy—an approach that continued after control of the operation was officially turned over to NATO, specifically Britain and France. Allied jets were directed to deter attacks on Benghazi and other NTC-held positions, not to win the revolution for them. NTC forces, untrained and poorly armed, were no match for Gaddafi’s professional army. On the other hand, loyalist forces were met by heavy NATO air strikes whenever they tried to advance into rebel-held territory. Libya was bifurcated. With Gaddafi still alive and in charge, this was the only way Obama Administration policy could have played out.

No one knows whether Gaddafi’s angry bluster—the rants that prompted Western officials to attack—would have materialized in the form of a massacre. It is clear, on the other hand, that Libyans on both sides of the front are paying a high price for the U.S.-created stalemate.

At least one million out of Libya’s population of six million has fled the nation or become internally displaced refugees. There are widespread shortages of basic goods, including food and fuel. According to the Pakistani newspaper Dawn, the NTC has pulled children out of schools in areas they administer and put them to work “cleaning streets, working as traffic cops and dishing up army rations to rebel soldiers.”

NATO jets fly one sortie after another; the fact that they’re running out of targets doesn’t stop them from dropping their payloads. Each bomb risks killing more of the civilians they are ostensibly protecting. Libyans will be living in rubble for years after the war ends.

Coalition pilots were given wide leeway in the definition of “command and control centers” that could be targeted; one air strike against the Libyan leader’s home killed 29-year-old Mussa Ibrahim said Saif al-Arab, Gaddafi’s son, along with three of his grandchildren. Gaddafi himself remained in hiding. Officially, however, NATO was not allowed to even think about trying to assassinate him.

Pentagon brass told Obama that more firepower was required to turn the tide in favor of the ragtag army of the Libyan National Transitional Council. But he couldn’t do that. He was faced with a full-scale rebellion by a coalition of liberal antiwar Democrats and Republican constitutionalists in the U.S. House of Representatives. Furious that the President had failed to request formal Congressional approval for the Libyan war within 60 days as required by the 1973 War Powers Resolution, they voted against a military appropriations bill for Libya.

The planes kept flying. But Congress’ reticence now leaves one way to close the deal: kill Gaddafi.

As recently as May 1st,, after the killing of Gaddafi’s son and grandchildren, NATO was still denying that it was trying to dispatch him. “We do not target individuals,” said Lieutenant General Charles Bouchard of Canada, commanding military operations in Libya.

By June 10th CNN television confirmed that NATO was targeting Libya’s Brother Leader for death. “Asked by CNN whether Gaddafi was being targeted,” the network reported, “[a high-ranking] NATO official declined to give a direct answer. The [UN] resolution applies to Gaddafi because, as head of the military, he is part of the control and command structure and therefore a legitimate target, the official said.”

In other words, a resolution specifically limiting the scope of the war to protecting civilians and eschewing regime change was being used to justify regime change via political assassination.

So what happens next?

First: war comes to Washington. On June 14th House of Representatives Speaker John Boehner sent Obama a rare warning letter complaining of “a refusal to acknowledge and respect the role of Congress” in the U.S. war against Libya and a “lack of clarity” about the mission.

“It would appear that in five days, the administration will be in violation of the War Powers Resolution unless it asks for and receives authorization from Congress or withdraws all U.S. troops and resources from the mission [in Libya],” Boehner wrote. “Have you…conducted the legal analysis to justify your position?” he asked. “Given the gravity of the constitutional and statutory questions involved, I request your answer by Friday, June 17, 2011.”

Next, the stalemate/quagmire continues. Britain can keep bombing Libya “as long as we choose to,” said General Sir David Richards, the UK Chief of Defense Staff.

One event could change everything overnight: Gaddafi’s death. Until then, NATO and the United States must accept the moral responsibility for dragging out a probable aborted uprising in eastern Libya into a protracted civil war with no military—or, contrary to NATO pronouncements, political—solution in the foreseeable future. Libya is assuming many of the characteristics of a proxy war such as Afghanistan during the 1980s, wherein outside powers armed warring factions to rough parity but not beyond, with the effect of extending the conflict at tremendous cost of life and treasure. This time around, only one side, the NTC rebels, are receiving foreign largess—but not enough to score a decisive victory against Gaddafi by capturing Tripoli.

Libya was Obama’s first true war. He aimed to show how Democrats manage international military efforts differently than neo-cons like Bush. He built an international coalition. He made the case on humanitarian grounds. He declared a short time span.

In three short months, all of Obama’s plans have fallen apart. NATO itself is fracturing. There is talk about dissolving it entirely. The Libya mission is stretching out into 2011 and beyond.

People all over the world are questioning American motives in Libya and criticizing the thin veneer of legality used to justify the bombings. “We strongly believe that the [UN] resolution [on Libya] is being abused for regime change, political assassinations and foreign military occupation,” South African President Jacob Zuma said this week, echoing criticism of the invasion of Iraq.

Somewhere in Texas, George W. Bush is smirking.

Ted Rall is an American political cartoonist, columnist and author. His most recent book is The Anti-American Manifesto. His website is rall.com.

(C) 2011 Ted Rall, All Rights Reserved.