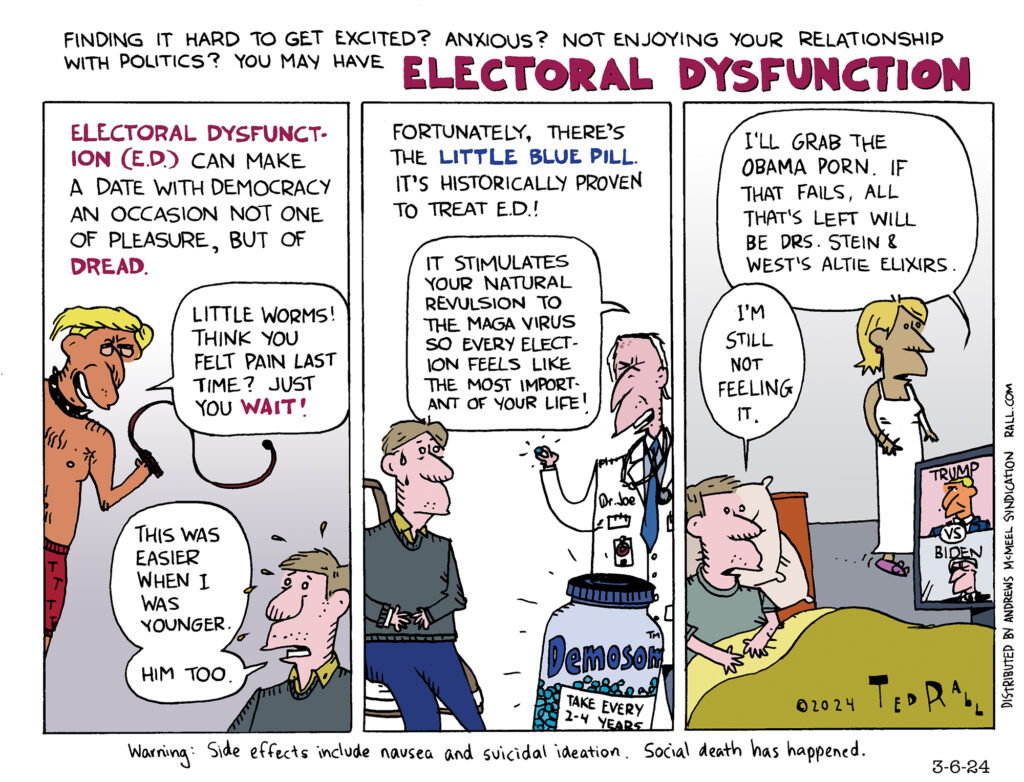

Finding it hard to get excited about your next date with democracy? You may be suffering from Electoral Dysfunction.

Wanted: Continuity Editors

The world needs more continuity editors.

Filmmakers hire them to check for plot holes. Like, in “Forrest Gump” the lead character’s friend Lieutenant Dan couldn’t have invested their money in Apple Computer in 1976, because the company didn’t go public until four years later. Or, in “Pulp Fiction” when hitmen played by Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta narrowly avoid being shot, the bullet holes appear in the wall behind them before the first shot is fired.

Continuity editors ensure that a movie makes sense, has a consistent look, sound and feel throughout, and moves at the right pace or combination of paces. They axe scenes that don’t advance the plot and insert new ones to fill in explanations and backgrounds in order to smooth out awkward transitions.

They track the big picture.

Hollywood isn’t the only place that needs them.

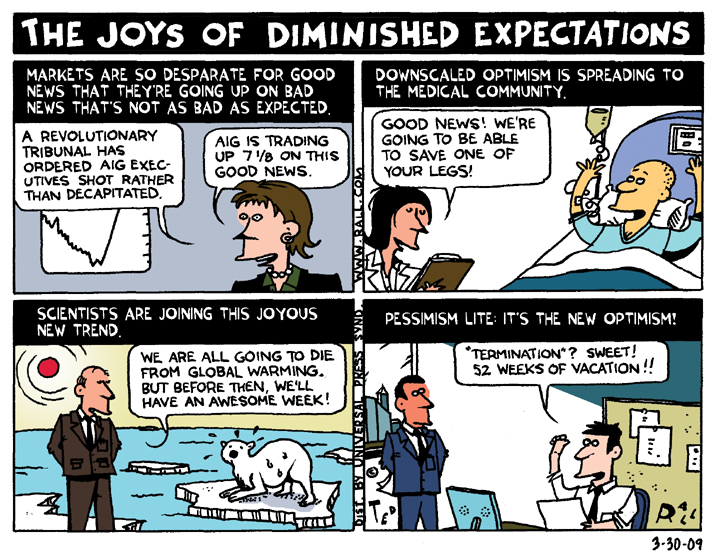

As the United States keeps sliding its slimy way through economic and sociopolitical decline toward the bubbly brown pit of collapse, our desperate need for people tasked with keeping track of the big picture and given the power to fix inconsistencies—or have access to those with that power—becomes increasingly apparent.

The biggest, most storied organizations have a C-something-O for everything from CFO to CIO to CTO to CDO (diversity). Few (I’d say all but I must allow for the fact that I do not and cannot know everything and everyone) employ a person who brings an outsider’s viewpoint to the deep inside of a corporate boardroom.

Large news organizations like The New York Times, for example, compile, process and disseminate a product whose breadth and depth objectively looks and feels like a miracle every single day. Yet the Times would benefit from an editor with a bird’s-eye view.

Because the left hand of the New York Times Book Review, a Sunday supplement, doesn’t know what the right hand of the features editors who labor in the daily editions is up to, the paper often runs two or even three reviews of the same title. Meanwhile, it fails to review most titles entirely.

Pundits on the op-ed page and analysts in the business section crank out one prognosis after another, but no one ever analyzes their record of success or failure in order to determine whether they are worth paying attention to (I’m looking at you, Thomas Friedman).

Newspapers don’t see what’s missing; a country whose voters are 38% pro-socialist might like a socialist opinion columnist. No one ever takes a beat to consider the possibility that a nation in which R&B/hiphop has dominated music charts for years might not respond well to a music section in which jazz (1% of sales) and classical (also 1%) receives disproportionately high coverage.

Our for-profit medical system is sorely lacking in many respects. One that leaps out is how à la carte recordkeeping makes it so that no one other than the patient themself enjoys comprehensive knowledge of a person’s health.

My general practitioner, for example, maintains records of my vaccinations, lab test results, examination history and back-and-forth communications. She does not, however, have access to the files and test results collected by my pulmonologist or other specialists, some of whom I see outside my insurance network. Nor can she see the stuff from my local urgent care clinic or the doctors I’ve seen in other states or other countries, or hospital emergency rooms, or from physicians I saw in the past but who have since retired. My dental records, themselves segregated between a dentist and an orthodontist, are similarly inaccessible to my GP. This is the result of the artificial insurance divide between dental and medical care that persists despite the proven link between oral health and such “non-dental” ailments as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, stroke and heart disease. Eye care falls into the same “non-medical” category—again, contrary to science and common sense. No one has a comprehensive understanding of Ted Rall’s medical history except Ted Rall—and he didn’t go to medical school.

Everyone ought to be assigned to a big-picture medical professional who pores over all these records in search of patterns that may indicate an undiagnosed illness. Many lives could be saved; hell, insurance companies save cash when patients detect problems early, not that I care about those scum. But Americans are so accustomed to dysfunction (in this case, non-function) that we haven’t even begun to discuss the need for an integrated medical records database accessible by any licensed medical professional, much less a caste of medical analysts whose job it is to try to anticipate problems.

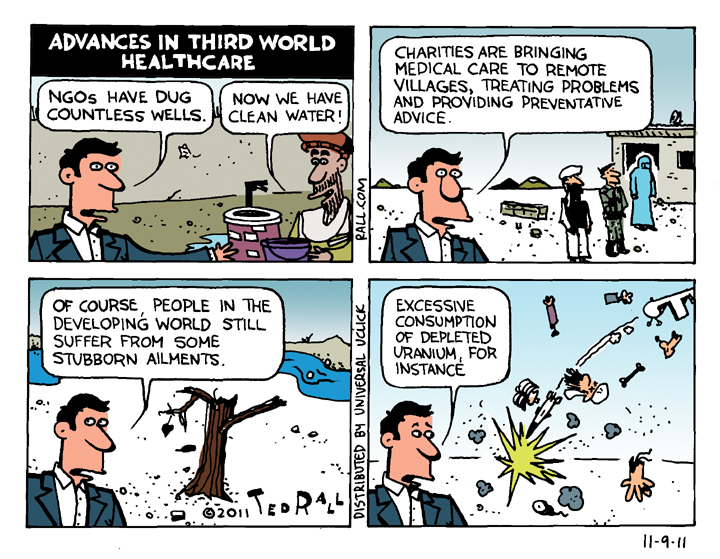

Like most societal shortcomings, our continuity editor-lessness comes straight from the top of the class divide: political and corporate elites. As much as our CEOs’ and political leaders’ smallmindedness is casting us adrift, no one is suffering higher opportunity costs than they are. A national high-speed rail system—the kind every other advanced country has—would open up development of new manufacturing, work and living spaces all over the nation. It would cost at least $1 trillion.

So it won’t happen any time soon.

But we spend three-quarters of a trillion bucks on “defense” every year—a budget replete with waste before you consider that the entire purpose of military spending is not merely wasteful but obscenely destructive. Slash 95% of that crap and national security would not suffer one whit. To the contrary, it would free up billions for worthwhile programs like making college free, modernizing public schools and a socialized healthcare system. Building new sectors and infrastructure from scratch generates more profits than maintaining what already exists. But they can’t even begin to think about thinking about such things, much less see them.

If and when the Revolution arrives, some of the formerly-rich may think to themselves as they journey atop their tumbrels: I should’ve hired a continuity editor.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

We Need a Centralized Medical System Too

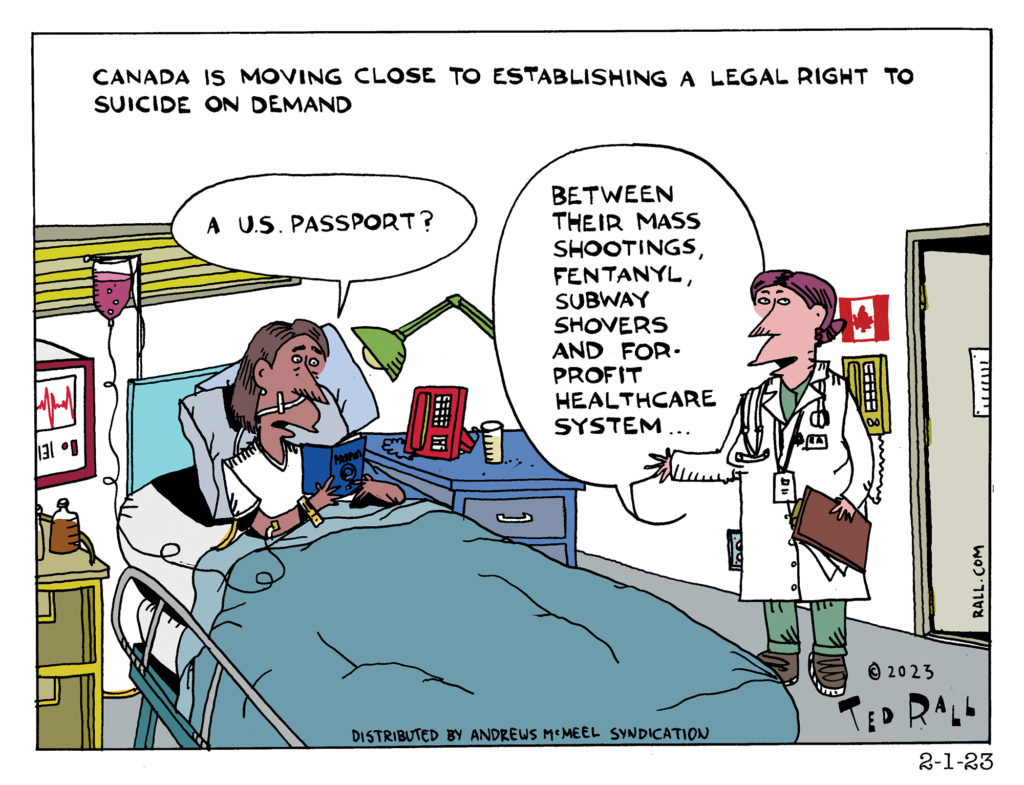

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare two fundamental flaws in the American healthcare system.

Number one: There’s a reason that other rich countries treat healthcare as a taxpayer-financed social program. Employer-based health insurance was stupid pre-COVID-19 because our economy was already steadily transitioning from traditional full-time W-2 jobs to self-employment, freelance and gig work. The virus has exposed the insanity of this arrangement. Millions of people have been fired over the last two months; now they find themselves uninsured during a global health emergency. The unemployed theoretically face fines for the crime of no longer being able to afford to buy private healthcare.

The second inherent flaw in the U.S. approach is that it’s for profit. Greed creates an inherent incentive against paying for preventative and emergency care. Even people who are desperately ill with chronic conditions see 24% of legitimate claims denied.

When your insurance company issues a denial, they don’t merely pocket that payment. They also add to future profits. Even if you’re insured, the hassle of knowing that you might get hit by a surprise bill for uncovered/out-of-network charges makes you more likely to stay home rather than to risk seeing a doctor or filling a prescription and going broke. “Visits to primary care providers made by adults under the age of 65…dropped by nearly 25% from 2008 to 2016” due to routine denials by insurers, reports NPR.

Denials also create a societal effect: news stories about patients with insurance receiving bills for thousands of dollars after being treated for COVID-19, even just to be tested, prompt people to stay away from hospitals and try to ride out the disease at home. Some of those people die.

There’s another, third structural problem exposed by the pandemic—but it’s not receiving attention from public policy experts or the media. I’m talking about America’s lack of a centralized healthcare system.

A centralized healthcare system has nothing to do with who pays the doctor. A centralized system can be fully socialized, government-subsidized or fully for-profit. In such a scheme all patient records are stored in a central online database accessible to physicians, pharmacists and other caregivers regardless of where you are when you need care. If you fall ill while you’re on a trip away from home, the admitting nurse at a walk-in clinic or hospital has instantaneous access to your complete medical history.

The current system is primitive. Data is not transferable between doctors or medical systems without a patient’s directive, which inexplicably is often required by the obsolete technology of sending a fax. That assumes the sick person is sharp enough to remember which of his previous doctors did what when. And that’s it’s not a weekend or national holiday or a Wednesday, when some doctors like to golf.

Unless a patient happens to be wearing a medical alert bracelet, there is currently no way to determine whether an unconscious victim is allergic to a drug, has a chronic illness or that there’s a treatment regimen proven to be more effective for them. Even if the patient is alert and conscious, a new doctor may ignore her request for a specific medication in favor of cookie-cutter one-size-fits-all treatment.

A few months ago I developed the classic symptoms of what we now know to be COVID-19. I live in New York. I succumbed while on business in LA. Trying in vain to fight off a relentless dry cough, difficulty breathing and day after day of brutal aches and fever, I visited a CVS walk-in clinic. I have a long history of respiratory illnesses: asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, swine flu. I requested a third- or fourth-generation antibiotic since I knew from experience that I would inevitably decline with anything less. “We do not treat viral infections with antibiotics,” the nurse, a charmless Pete Buttigieg type, pompously declaimed. I pointed out that viral lung infections usually have a bacterial component that should be treated with antibiotics.

This would not have been a issue back home in New York, where both my general practitioner and my pulmonologist know my medical history. Either doctor would have prescribed a strong antibiotic and a codeine-based cough syrup.

Because I happened to be in LA, I left CVS empty-handed.

I declined.

It got to the point that I couldn’t walk 100 feet without pausing to catch my breath. I felt like I was going to die.

I called my doctor back in New York. She called in a prescription to the same CVS. It helped arrest my decline. But I wasn’t getting better.

I visited a different walk-in clinic, in West Hollywood. It was a better experience. They tested me for flu (negative), X-rayed me (diagnosis was early stage- pneumonia) and put me on a nebulizer. I began a slow recovery.

A centralized system would have been more efficient. The CVS nurse would have seen my history of non-response to treatment devoid of strong antibiotics. He also might have taken note of my pulmonologist’s effective use of a nebulizer to treat previous bouts of bronchitis and pneumonia. I might have been prescribed the proper medication and treatment as much as a week sooner.

COVID-19 almost certainly would have been detected in the United States sooner if we had a centralized medical system. “One example of a persistent challenge in the early detection of health security threats is the lack of national, web-based databases that link suspected cases of illness with laboratory confirmation. This leaves countries vulnerable, as they cannot accurately and quickly identify the presence of pathogens to minimize the spread of disease,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Algorithms can automatically scan massive volumes of information for signs of novel infectious diseases, help identify potential problems and focus responses where they are needed most.

How many people’s lives could have been saved if lockdown procedures had begun earlier? If public health officials had seen the coronavirus coming back in December—or November—they might have been able to protect vulnerable populations and avoid a devastating economic shutdown.

There are substantial privacy considerations. No one wants a hacker to find out that they had an STD or an employer to learn about documented evidence of substance abuse. Keeping a centralized healthcare system secure would have to be a top priority. On the other hand, there is no inherent shame in any kind of illness. In a nightmare scenario in which medical records were to somehow become public, no one would have anything to hide or any reason to look down on anyone else.

We can’t pretend to be a first world country until we join the rest of the world by abolishing corporate for-profit healthcare and decouple insurance benefits from employment. But reform without centralization would be incomplete.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of the biography “Bernie,” updated and expanded for 2020. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)