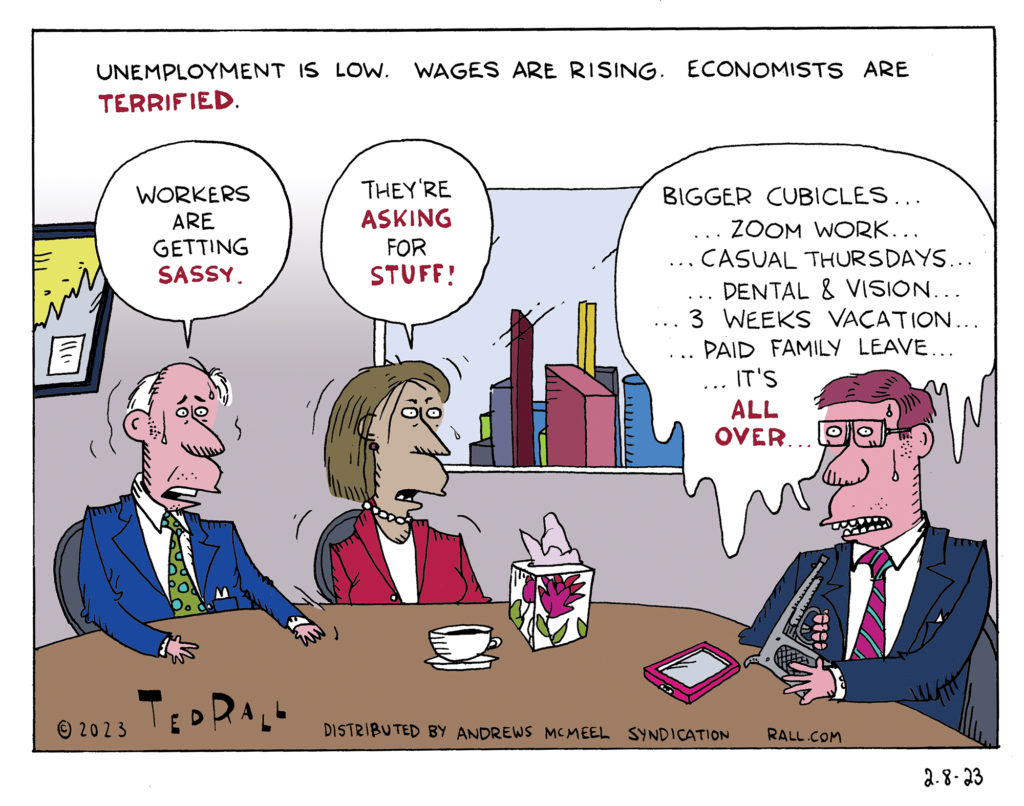

Unemployment fell to the 3.4%, the lowest on record since the early days of the Richard Nixon administration. Jobs have never been easier to find and workers are able to get raises. The American economy, however, relies on cheap compliant labor, so economists are worried.

Open Office Spaces: If Only Skateboards Were Allowed

Workers hate hate hate open office spaces, which they say make them feel undignified, constantly distracted and cramps their personal space. But corporations think workers should just tolerate open spaces anyway. Oh, the joy of open office spaces.

The Freelance Workers Manifesto

Originally published by Breaking Modern:

Occupy Wall Street is no more, but its demand that America treat its workers better remains at the forefront of the national conversation.

Jobs and stagnant salaries will probably be important issues in the 2016 presidential campaign. Even Republicans, traditionally the party of business, are building their platform around the problem of rising income inequality and how conservative ideas can alleviate it. President Obama wants to improve conditions for American workers by requiring employers to provide guaranteed paid sick days and family leave, and making it easier for them to join a union.

All great news for workers, who have been taking it on the chin since at least the 1970s, the last time real wages kept up with inflation. Yet there’s a glaring gap in the discussion: freelancers.

Ten million Americans are completely self-employed — that’s way up, from just 1.3 million people in 2001. A whopping 53 million people devote part of their workweek to freelance work. “Even though there may not be jobs in the conventional sense, there is still work,” urban analyst Bill Fulton told Forbes. “That’s the whole idea of the 1099 economy. It’s just a different way of organizing the economy.”

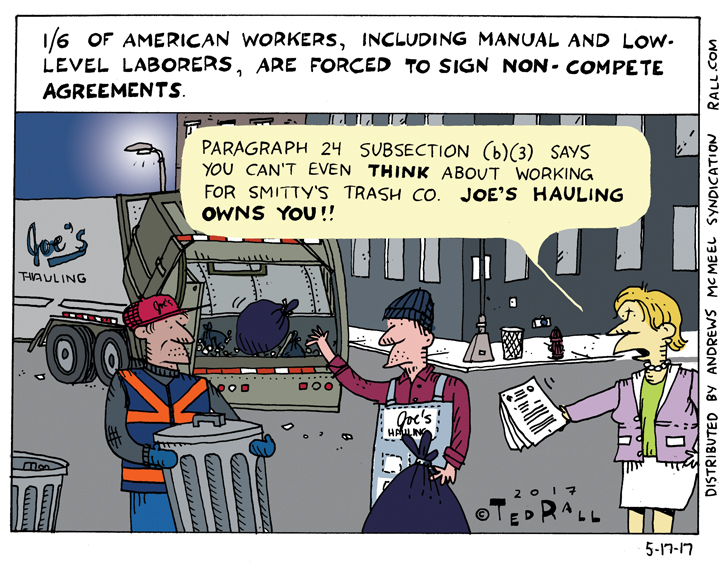

When politicians and the media talk about workers and how to improve their lot, independent contractors and entrepreneurs are almost always left out. But self-employment isn’t going away. Though the current tentative economic recovery has caused a slight dip in the percentage of U.S. workers who receive 1099s (as opposed to W-2s) at the end of each year, labor experts anticipate that more workers will become freelancers. This will either be by choice or, after being laid off, out of necessity. As automation and international outsourcing continue to reduce the demand for full-time workers, and CEOs increasingly turn to the “contingent workforce” to fulfill their staffing needs on an as-needed basis, being dumped like a dirty napkin when demand slackens is common.

The software company Intuit predicts that a whopping 40% of American workers will be freelancers, contractors or temporary workers by the year 2020.

Are proposed reforms enough?

No. None of the proposed reforms would do anything to help these lone wolves.

When you work for yourself there’s no employer to give you paid vacation days, much less paid sick days or parental leave. What are you going to do, unionize against yourself? Forget about going on strike for higher wages — which, given the fact that 12% of freelancers are on food stamps, the self-employed could use higher wages.

Freelancers earn less than full-timers. They work longer hours. They’re less economically secure. Because they can’t afford to say no when a possible client calls, their time isn’t their own, even on weekends and holidays. Speaking of which: what holidays?

Freelancers earn less than full-timers. They work longer hours. They’re less economically secure. Because they can’t afford to say no when a possible client calls, their time isn’t their own, even on weekends and holidays. Speaking of which: what holidays?

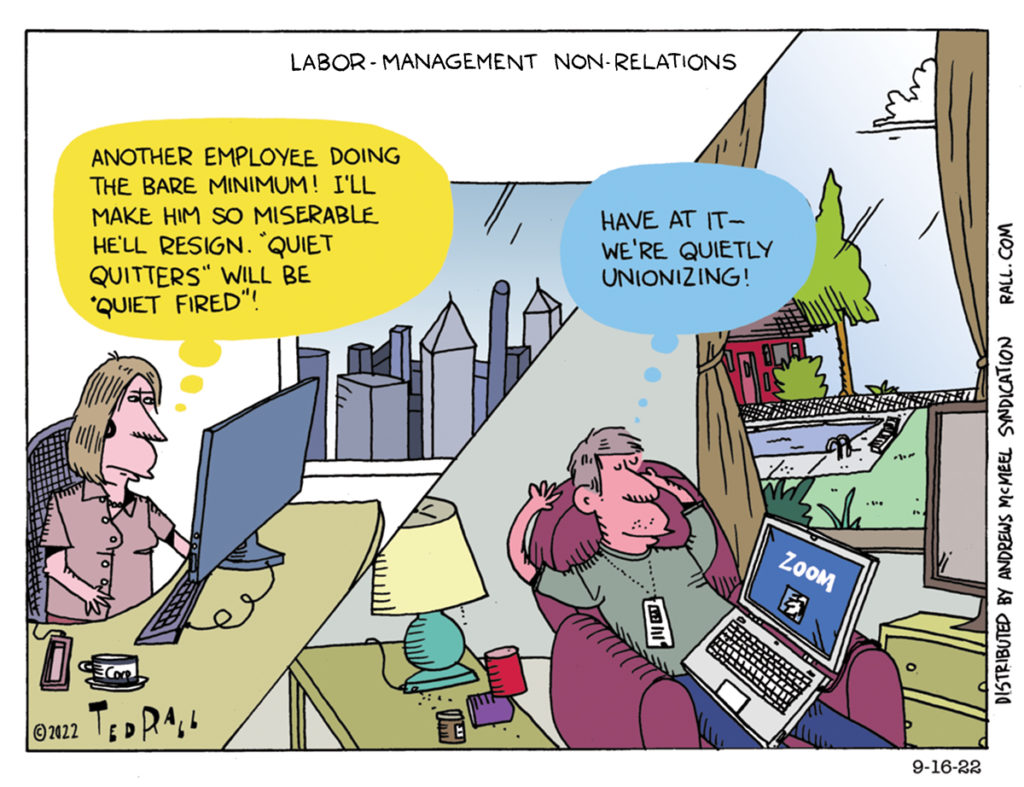

If the balance between laborer and management has inexorably shifted toward the latter in traditional workplaces over the past half-century, the move toward an increasingly insecure, off-and-on-again workforce will only accelerate that trend. It’s a seismic shift and the main force driving down average wages. Yet public policy hasn’t merely failed to catch up — it hasn’t even begun to think about it.

As David Atkins wrote in Washington Monthly: “Simply letting the economy slide into the enforced uncertainty of the freelance economy without helping workers achieve dignity and stability is not an acceptable outcome.” But how can we avoid it?

Sara Horowitz of the Freelancers Union (not a union in the traditional sense, mostly just a way for independent workers to buy pooled health insurance) tells The Washington Post that one way to even out the feast-or-famine problem would be for Congress to authorize 529-like savings schemes. “Freelancers could be allowed to set up pre-tax accounts for their earnings that would go tax-free if they fell below a certain level, to keep them out of poverty during dry spells. In England, government officials have experimented with a ‘central database of available hours‘ as a public option for freelance work scheduling.”

Also in the Post: “As a general philosophy, social welfare benefits might need to shift towards how they work in Europe, where entitlements are attached to the individual, rather than their relationship with an employer. Some academics have described a new ‘dependent contractor’ status that would cover workers who serve mostly one client. These workers, the argument goes, should have more protections — unemployment insurance, for example, or workers compensation — than those who pick and choose their assignments from a number of different sources.”

Good suggestions, but pretty weak tea compared to the really big problems — much lower pay, much less security — faced by the new rising class of on-demand workers.

The best way to reverse decreasing wages

The best way to reverse downward pressure on wages would be for the federal government to set prices for labor on everything from the cost of a new roof to the price per word received by a writer to create an article like this one. For Americans accustomed to letting the “magic of the marketplace” govern their financial destinies, this would be a radical reform. But it’s not unprecedented. Wage and price controls have been deployed in India, the world’s biggest democracy. In 1971 President Nixon went after inflation driven by predatory corporations by freezing all wages and prices — a move conservatives declared a failure but that dramatically helped working poor people like my mom, who still says it saved our lives (even though she hated Nixon).

This would require a new government bureaucracy, but hey, hiring federal workers would reduce unemployment. Setting minimum wages for freelance work would be challenging, but experts know the marketplace. As a writer, I know that outfits that offer $25 for 1,000 words ought to be ashamed of themselves — no one should write anything for less than $1 a word.

Congress should extend protections against workplace discrimination based on race, age, gender, sexual orientation and disability to allow wronged freelancers to sue for compensatory as well as punitive damages.

Companies and individuals who engage the services of freelance workers should be required to pay into a general compensation fund managed by the federal government. This would probably be remitted as a percentage of compensation. Freelancers should be able to draw on the fund to take paid vacation and sick time off, as well as paternity and maternity benefits.

The only way to prevent American freelance workers from sliding into a chattel class indicative of life in a third-world country will be to give them the same rights, privileges and protections as those enjoyed by full-time workers.

Which, of course, will likely reduce the number of employers who transition from a full-time to an on-demand workforce.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Why Does the Military Treat Soldiers Like Children?

Why Doesn’t the Pentagon Let Its Employees Be All They Can Be?

The U.S. military isn’t supposed to allow child soldiers to enlist (though reality can differ). So why does it treat recruits like children?

Other than religious avocations, it’s impossible to think of another major employer that asks as much of prospective workers as the Pentagon, yet offers so little. Salaries are lower than for comparable private-sector jobs. The skills one acquires don’t translate easily to other fields. The risks couldn’t be higher. But most baffling, for a force supposedly dedicated to defending our freedom, is that they get little freedom of their own.

You’ve heard the drill sergeant line in movie boot-camp scenes: “You are now the property of the United States of America.” That’s true. Once signed up, soldiers and sailors can be assigned anywhere, to any job, completely at their commanders’ discretion. Sometimes they take your skills, desires or ambitions into consideration. Not always.

Active duty, recruiters tell young men and women, lasts two to five years — after which they’re supposed to wind up in the reserves, free to go home unless there’s a national emergency. But the President can invoke the “stop-loss” provision, which means you can get stuck as long as eight.

It’s time for the military to catch up to the modern workplace.

American workers are getting more of a raw deal in many ways: lower wages and benefits, companies that ignore the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, no more pensions. Yet the fraying of the postwar labor-management social contract has also provided employees with greater flexibility. You may have to work three crappy jobs to make ends meet, but crappy jobs are easy to replace. You can move to another city and probably find three crappy jobs there. You certainly don’t have to worry about one of your crappy employers shipping you off to Afghanistan, much less coming home in a coffin.

The military’s insistence on treating its workers like property to be disposed of at whim is obsolete, making it increasingly difficult — even in a high-unemployment economy — to compete for recruits.

One example making recent headlines is the Air Force’s increasingly severe shortfall of fighter pilots. A new signing bonus totaling nearly a quarter million bucks (albeit spread over nine years), isn’t enough to compensate for starting salaries ($34,500 to $97,400) — not when the airlines are paying a median salary of $103,210 to commercial jet pilots. Nor are benefits like lower taxes and on-base housing.

“The military is difficult on the family with all the moving around,” Rob Streble, a former Top Gun and an official of the union that represents US Airways pilots, told The Los Angeles Times. “I added more stability by joining the airline.”

“People have no idea how hard it is when you have to move your family all the time,” admits John Wigle, a former F-15 pilot who is now a program analyst in the USAF’s operations, plans and requirements directorate.

Freedom was a determining factor for me.

The recruiter manning the desk at the Army Recruiting Office in Kettering, Ohio was way into me when I walked through the door at age 18. I had what they’re looking for: I was human, sentient, and ambulatory. I was also a catch: a straight-A engineering student who’d gone to an Ivy League school on full scholarship. When Reagan slashed financial aid for me and millions of other college students, I considered other options.

I aced the Army aptitude test. This didn’t surprise me, considering the lugs sitting in the test center next to me. Anyway, I test great. I drew the attention of a big über recruiter for the entire Midwest who wouldn’t stop calling. He made a lot of promises. We’ll fast-track you for officer! When you get out, we’ll pay your college tuition! What’s that, you want to draw cartoons for Stars and Stripes, just like Bill Mauldin during World War II? Sure, why not?

As a child of divorce, I’d learned to get promises in writing. Which, of course, military recruiters can’t and won’t do. (At the time, the Army paid “up to” $5,000 a year for college. Columbia was $13,000.) Sure, despite Reagan’s efforts, we weren’t at war. So getting killed was unlikely. But they could send me anywhere in the world, assign me to any job they wanted (from a military website today: “The Military will make every effort to match your interests and aptitudes with its needs. However, job assignments are ultimately made based on Service needs, as well as individual skills and test scores”), and the bottom line was, there’d be nothing I could do but salute and say yessir. That was the end of my flirtation with a military career. I wanted the basic freedom to choose where I lived and what I did for work.

I’m not alone. 89% of young Americans say they’d never consider a military career.

It will be a bummer for military officers, by temperament the biggest control freaks ever, but sooner or later they’re going to have to face reality: slavery is over. If you want to find quality sailors and soldiers, you have to treat them like adults. Let recruits choose their positions and where they live. Act like they’re workers. Which they are. For example, why can’t soldiers put in for vacation as opposed to applying for leave? If their chosen job is no longer needed, fine — they should be free to go. Yes, even during wartime — at least during the optional wars of choice the United States has fought since 1945.

During an invasion or serious attack against the U.S. by another nation, obviously, all bets are off. But don’t worry — that hasn’t happened since 1812.

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in 2014 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL

SYNDICATED COLUMN: You’re Not Underemployed. You’re Underpaid.

The Case for Shiftlessness

No bank balance. Nothing in your wallet.

“I’m broke,” you say. “I need a job.”

Or:

Perhaps you have a job. Then you say:

“I’m broke. I need a better job.”

You’re lying. And you don’t even know it.

You don’t need a job.(Unless you like sitting at a desk. Working on an assembly line. Non-dairy creamer in the break room. In which case I apologize. Freak!)

You don’t need a job. You need money.

We’ve been programmed to believe that the only way to get money is to earn it.

(Unless you’re rich. Then you know about inheritance. In 1997, the last year for which there was solid research done on the subject, 42 percent of the Forbes 400 richest Americans made the list through probate. Disparity of wealth has since increased.)

It’s time to separate income from work.

For two reasons:

It’s moral. No one should starve or sleep outside or suffer sickness or go undereducated simply due to bad luck—being born into a poor family, growing up in an area with high unemployment, failing to impress an interviewer.

It’s sane.

“American workers stay longer at the office, at the factory or on the farm than their counterparts in Europe and most other rich nations, and they produce more over the year,” according to a 2009 U.N. report cited by CBS. Thanks to technological innovations and education, worker productivity—GDP divided by total employment—has increased by leaps and bounds over the years.

U.S. worker productivity has increased 400 percent since 1950. “The conclusion is inescapable: if productivity means anything at all, a worker should be able to earn the same standard of living as a 1950 worker in only 11 hours a week,” according to a MIT study.

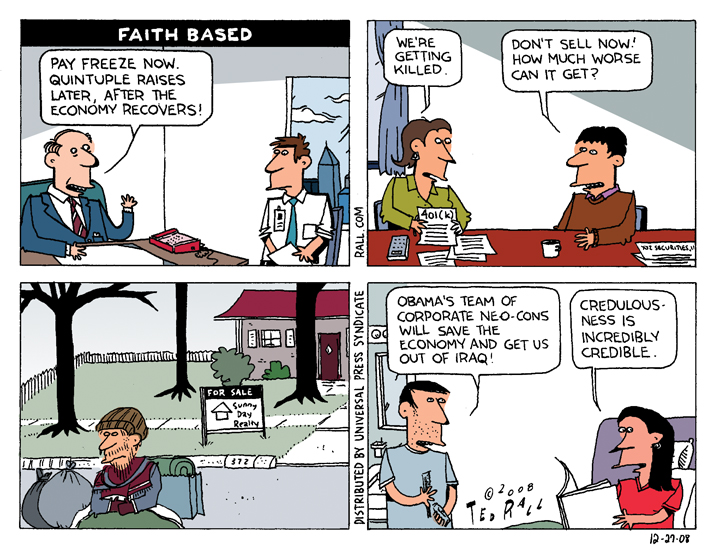

Obviously that’s not the case. American workers are toiling longer hours than ever. They’re not being paid more —to the contrary, wages have been stagnant or declining since 1970. Numerous analyses have established that, especially since 1970, the lion’s share of profits from productivity increases have gone to employers.

Workers are working longer hours. But fewer people are working. Only 54 percent of work-eligible adults have jobs—the lowest rate in memory. Which isn’t surprising. Because there are fixed costs associated with employing each individual—administration, workspace, benefits, and so on—it makes sense for a boss to hire as few workers as possible, and to work them long hours.

This witches’ brew—increased productivity coupled with higher fixed costs, particularly healthcare—have led companies to create a society divided into two classes: the jobless and the overworked.

Unemployment is rising. Meanwhile, people “lucky” enough to still have jobs are creating more per hour than ever before and are forced to work longer and harder.

Crazy.

And dangerous. Does anyone seriously believe that an America divided between the haves, have-nots and the stressed-outs will be a better, safer, more politically stable place to live?

Sci-fi writers used to imagine a future in which machines did everything, where people enjoyed their newfound leisure time exploring the world and themselves. We’re not there yet—someone still has to make stuff—but we should be closer to the imagined idyll of zero work than we are now.

If productivity increases year after year after year, employers need fewer and fewer employees to sustain or expand the same level of economic activity. But this sets up a conundrum. If only employees have money, only employees can consume goods and services. As unemployment rises, the pool of consumers shrinks.

The remaining consumers can’t pick up the slack because their wages aren’t going up. So we wind up with a society that produces more stuff than can be sold: Marx’s classic crisis of overproduction. Hello, post-2008 meltdown of global capitalism.

Silicon Valley entrepreneur Martin Ford warns that the Great Recession is just the beginning. In his 2009 book “The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future” Ford, “argues that technologies such as software automation algorithms, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics will result in dramatically increasing unemployment, stagnant or falling consumer demand, and a financial crisis surpassing the Great Depression,” according to a review in The Futurist.

The solution is clear: to guarantee everyone, whether or not he or she holds a job, a minimum salary sufficient to cover housing, transportation, education, medical care and, yes, discretionary income. Unfortunately, we’re stuck in an 18th century mindset. We’re nowhere close to detaching money from work. The Right wants to get rid of the minimum wage. On the Left, advocates for a Universal Living Wage nevertheless stipulate that a decent income should go to those who work a 40-hour week.

Ford proposes a Basic Income Guarantee based on performance of non-work activities; volunteering at a soup kitchen would be considered compensable work. But even this “radical” proposal doesn’t go far enough.

Whatever comes next, revolutionary overthrow or reform of the existing system, Americans are going to have to accept a reality that will be hard for a nation of strivers to take: we’re going to have to start paying people to sit at home.

(Ted Rall’s next book is “The Book of Obama: How We Went From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt,” out May 22. His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2012 TED RALL