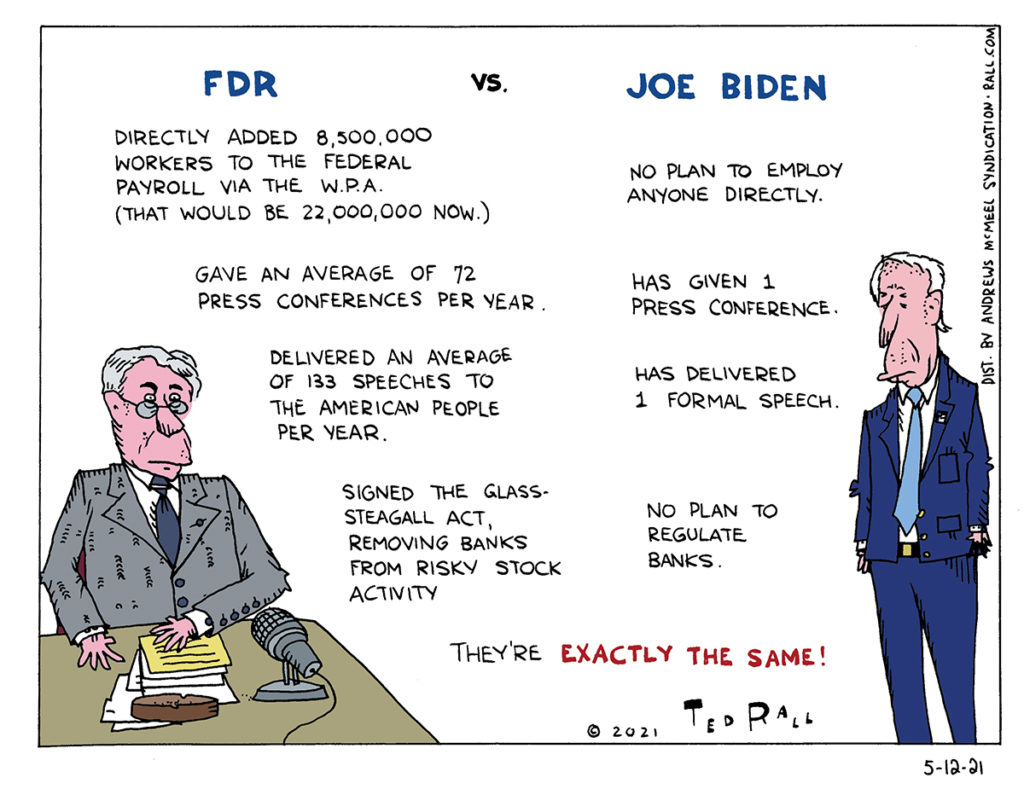

Democrats and their media allies are currently comparing the legislative agenda of Joe Biden to the sweeping ambition of Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the beginning of the Great Depression. But there’s really no comparison.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: The New Generation Gap: Gen X vs. Gen Y

The Gen X-Millennial Generation Gap

Every 20 years ago, Time depicts people in their 20s as “lazy, entitled, selfish and shallow.” This time the target is the Millennial generation (Americans born between roughly 1980 and 2000, with Baby Boomer parents). According to (cough cough) the Boomer-run media, twentysomethings/Gen Y/Millennials are narcissists.

Whatever.

Back in 1990, Time was smearing Gen X as shallow, apolitical, unambitious shoe-gazers.

“[Gen Xers] have trouble making decisions. They would rather hike in the Himalayas than climb a corporate ladder. They have few heroes, no anthems, no style to call their own. They crave entertainment, but their attention span is as short as one zap of a TV dial. They hate yuppies, hippies and druggies. They postpone marriage because they dread divorce. They sneer at Range Rovers, Rolexes and red suspenders. What they hold dear are family life, local activism, national parks, penny loafers and mountain bikes.” (Penny loafers? Really?)

Back then we Gen Xers defended our collective honor by alternating between the “we do not suck, at least not in the way you say we suck” and “anyway, if we do suck, it’s your fault, old farts” arguments. Gen Y is manning its rhetorical ramparts the same way.

Here we go again.

Sort of.

You know what’s wrong with young people today?

Not much. Not according to me or my friends. We’re fine with younger people.

Which is weird.

Gen Xers get along well with people in their 20s and 30s — certainly a lot better than those in their 40s did with us when we were young.

We like Gen Y. We respect them. We don’t chafe, for example, at working under a younger boss. We ask them advice. OK, mostly about tech stuff. I learned about WordPress and Hootsuite and Gawker and Wii from 20ish friends. Mostly, we like the same music and movies. (But they download stuff. Don’t they worry about ephemerality?)

Maybe the Millennials secretly hate us — you’d have to ask them — but if they do, they’re doing an excellent job of hiding it. We hang out. It’s good.

Sometimes, though — it’s not like it comes up a lot, just now and then — my Gen Xer cohorts let slip a complaint about our younger friends and colleagues:

Why are Millennials, um…well, there’s no other way to say it: kind of boring?

Young people today! So obedient. They believe politicians. What’s with that? Millennials go along to get along in corporate America. When they get laid off, they don’t get angry (like we did) — they adapt. They reinvent themselves. Gen Y music, movies, even their clothes: so conservative!

The Generation Gap of the 1960s and 1970s referred to the inability/refusal of “tune in, turn on, drop out” Baby Boomers to relate to their stodgy “we survived the Depression and won World War II so turn down that goddamn rock ‘n’ roll” Parents. Though decried at the time as sad and alienating, the dynamic of that demographic divide was as natural as could be. The young were loud, obnoxious, demanding and politically radical. The old were reserved, quiet and conservative, even reactionary. Kids were kids; parents were parents.

William Howe and Neil Strauss’ landmark book “Generations,” which traces the identities of American generation through popular culture and politics back to the colonial era, depicts dozens of epic clashes between old codgers vs. youthful insurgents. The young fight to be heard. The old yell at them to shut up. The old get older and quieter, the young mature and gain influence and replace them.

That’s how it was 200 years, and 20 years, ago. Just as their parents looked down on them, Boomers looked down on us Xers.

The Gen X/Y divide breaks this pattern.

We’re middle-aged and cynical and our tastes run to smart and sarcastic and anti-PC and antiauthoritarian, Tarantino/postpunk. We voted Green Party and never looked back, or for Obama but never expected much. Millennials are old and naïve and earnest and retro.

Millennial hipsters (who don’t dress hip — their hipsters are dorks) are militant nostalgists. They’ve revived the ancient traditions of our grandparents: martinis, old-fashioned cocktails like grasshoppers and mint juleps and, well, old fashioneds. They golf. They wear clothes from the 1930s. They watch go-go dancers. (Feminist radical lesbian ones.) They grow beards — not hippie beards, but retrosexual Civil War ones, paired with handlebar mustaches. They open restaurants — really good restaurants — whose menus and aesthetics harken back to the 19th century, staffed by waiters who take everything very seriously. You can elicit a dry chuckle. Not a bellylaugh. Certainly not a snide Xer sneer.

Steampunk could never have been a big Gen X thing. We’re scrappy and stripped down. They’re baroque.

Millennials didn’t just expect real Hope and Change. Four years later, they still do. When they got radical, they came up with the blink-and-you-missed it Occupy movement, which had as its centerpiece calls to reenact the Glass-Steagal Act.

Millennial pop culture is about flat affect: mumblecore movies and all-attitude-no-plot TV shows like “Arrested Development,” emo-influenced music, giant dollops of special nostalgia sauce everywhere, every member of every band dressed like they’re showing up to roof your house (but with Taliban beards). Opening concert greeting: “Hey.”

Graphic novels where it takes six pages for a leaf to fall off a tree.

Prose novels about nothing, printed preciously and packaged beautifully, thanks to the influential McSweeney’s empire.

Gentle, chatty movies and TV shows, not a series of scenes, but rather riffs of tone and mood.

Even their taste in cars is boring. And kind of dumb.

Boomers’ countless faults aside, let’s give them this: they knew what they wanted. They loved. They hated. They wanted revolution. Which was one of the things Xers hated about Boomers (Xers hate a lot): they came so close to revolution and they friggin’ gave up. Gen Y revolution? It’s hard to imagine such an — oblivious? unaccountably satisfied? — generation shooting anyone or blowing anything up. That, I think, gets close to the mystery of the Millennials. They’ve been horribly screwed — even more than us Gen Xers, and make no mistake, we were hosed big time.

Millennials are mired in student loan debt.

They will never make much money or get any government benefits or get much of anything out of the system.

After decades of warnings, the planet is finally, really, irreversibly, ruined. Their planet.

Why aren’t they pissed off?

(We need them to be. We’re too busy holding down four jobs.)

Parents, they say, shouldn’t have to bury their own children. It ain’t natural. Know what else is wrong? For the old to see the young as uptight codgers.

Not that Xers blame Yers for being uncool. Gen Xers, a self-deprecating generation from the beginning (what do you expect? society, politics, even the movies hated us — remember all those evil child horror movies like The Omen and It’s Alive?)

Writing in The New York Observer, Peter Hyman argues that Gen X and Gen Y shouldn’t be as cozy as they are. That it’s our (X’s) fault that Y hasn’t made its own mark:

“The old generational identities that once defined us have broken down, and the net result is a messy temporal mashup in which fortysomethings act like skateboarders, twentysomethings dress like the grandfather from My Three Sons, tweens attend rock concerts with their parents and toddlers are exposed to the ethos of hardcore punk.”

And it’s up to Gen X to fix it (like everything else, apparently):

“I know guys whose style of dress and off-duty interests haven’t changed a lick since college. They devote their free time to movies about comic-book heroes, to video games and to fantasy football. No, they aren’t hurting anybody. But perhaps what we really need to do is put on suits and take our wives out for expensive dinners, like our dads before us.”

That burns. I’m wearing skinny black jeans and a (vintage! from back in the day!) Dead Kennedys T-shirt as I write this. But I can’t afford a suit or an expensive dinner, thank you very much, Boomer scum.

Anyway, I don’t buy Hyman’s argument that passing the torch of our old cool (the Ramones, Beastie Boys) to the young “shortchanges” the young and “infantilizes” us oldsters. My fogie parents prosthelytized about Benny Goodman and Benny Hill and the Four Tops and guess what? It didn’t take.

One problem with writing about generational politics is that it requires sweeping generalizations. You can point to million exceptions. And of course there’s absolutely nothing anyone can do about it. These things simply are (if you believe, many many do not). Another is that you risk pissing people off…people you like.

To be clear, we Xers think you Millennials are awesome. We just wish you’d act your age.

Like, young.

(Ted Rall’s website is tedrall.com. His book “After We Kill You, We Will Welcome You Back As Honored Guests: Unembedded in Afghanistan” will be released in November by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.)

COPYRIGHT 2013 TED RALL

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Toxic Assets

Many Foreclosed Houses Are Infested by Mold

The next time someone tells you that capitalism is efficient, remember the mold houses.

I used to be a banker. Some of my customers had trouble making their loan payments. We usually had recourse to some sort of collateral—often real estate. But my bank really didn’t want to foreclose.

“We’re bankers,” my boss told me the first time this issue came up. “Not landlords.”

Back in the 1980s most banks held this view. Bankers sat on their butts in air-conditioned offices. They didn’t want to manage vacated properties, much less try to sell them. They understood banking. Banking was a straightforward business: take deposits, issue loans, collect the difference in interest as profit.

It was boring. Just the way they liked it.

My bank did a lot to avoid declaring a default. We lowered interest rates. We allowed skipped payments. Sometimes we even reduced principal.

Banking became exciting during the 1990s. Glass-Steagall got repealed, allowing formerly staid bankers to compete with high-flying Wall Street financiers in the securities business. Bank consulting firms invented big new fees for services that used to be free, like using an ATM.

Banks issued millions of home loans to borrowers whom they knew couldn’t afford to pay them back. Crédit Suisse estimates that such “liars’ loans” accounted for 49 percent of originations by 2006. Why they’d do it? Like mobsters, bank executives were “busting out” their companies—generating false short-term profits in order to collect annual performance bonuses. By the time the toxic chickens came home to roost, as they did in the form of the September 2008 financial crisis, they and their paychecks had moved on.

As the global financial system was in the midst of total collapse, greedy bankers conjured up a way to profit from the very misery they had caused. Rather than work with distressed homeowners who faced foreclosure (for example, refinancing subprime and adjustable rate mortgages into old-fashioned 30-year fixed mortgages) they dragged out the process in order to collect more late fees.

Banks were eager to foreclose. They were merciless. They evicted homeowners while they were on active-duty serving in Iraq and Afghanistan, a violation of federal law. They even evicted people who didn’t owe them a cent.

Now banks are sitting on top of nearly a million homes. “All told, [banks] own more than 872,000 homes as a result of the groundswell in foreclosures, almost twice as many as when the financial crisis began in 2007, according to RealtyTrac, a real estate data provider,” reports The New York Times. “In addition, they are in the process of foreclosing on an additional one million homes and are poised to take possession of several million more in the years ahead.”

Which is where the wonderful tragic tale of the mold houses comes in.

“In most homes,” reported NPR recently, “as residents go in and out and the seasons change, natural ventilation sucks moisture up to the attic and out through the roof. It’s called the ‘stack effect.’ And in many parts of the country, it’s driven by air conditioning in the summer and heat in the winter. But no one is going in or out of most foreclosed homes—regardless of climate—and the effects can be devastating.”

Far from the profit center imagined by freshly-minted analysts with MBAs, empty houses depreciate faster than a new car driving off the lot. They fall apart quickly. Mildew and mold sets in, some of it toxic.

“In some states, it’s estimated that more than half of foreclosed homes have mold and mildew issues,” reported NPR. “Realtors across the country say they’re seeing the problem in everything from bungalows to mansions.”

Turns out those old-fashioned bankers were on to something. Bankers shouldn’t become landlords.

A minor mold problem starts at $5,000 and can easily run $20,000 or more. Considering that the average house in the Midwest is valued at $136,000, that’s not insignificant. Many houses with toxic mold have to be demolished.

Greed may be good. But it doesn’t always pay.

(Ted Rall is the author of “The Anti-American Manifesto.” His website is tedrall.com.)

COPYRIGHT 2011 TED RALL