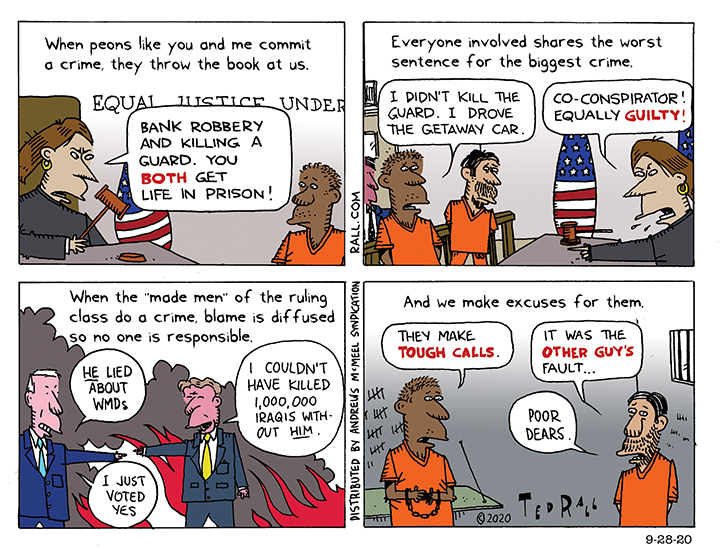

When Joe Biden gets criticized for voting for the war against Iraq, his defenders say that he wasn’t alone, that he had help from the Republicans. That, of course, is true. But it would never be an excuse for you or me.

SYNDICATED COLUMN: No Man is Above the Law — Except on College Campuses

Freshman orientation, Columbia University, New York City, Fall 1981: Now as then, there were speeches. A blur of upperclassmen, professors and deans welcomed us, explained campus resources and laid out dos and donts. At one point, the topic of the campus drug policy came up. “You can do whatever you want in your dorm room,” we were told, “just make sure it’s OK with your roommate.” A ripple of surprise swept the audience. Several students asked for elaboration of this don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy on illegal narcotics, and were told that they’d heard correctly.

One of my friends, who grew pot plants in his window, proved the wisdom of that advice. My pal’s Born Again Christian roomie, not consulted about his grow house scheme, attacked him in what became a legendary fistfight out of a Western.

No one was arrested, though there was a stern talking-to courtesy of the R.A.

(Columbia has since changed this policy.)

The weird alternative universe of law on campus is in the headlines again due to Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’ announcement that the Trump Administration plans to rewrite Obama-era Title IX rules to give male students accused of rape on college campuses more rights to defend themselves.

Under a 2011 directive university administrators were advised that their institutions could lose federal education funding unless they reduce the evidentiary standard for finding a defendant student guilty of sexual misconduct from “beyond a reasonable doubt” (the same as in criminal courts, in which jurors are asked to be roughly 90% or more certain of guilt to convict) to the lower “based on the preponderance of the evidence” standard used in civil courts (50% or more).

Victims rights advocates say campus rape is an epidemic problem, that local police can’t be trusted to take rape charges seriously or prosecute them aggressively, and that the relatively friendly campus tribunals of administrators operating under the lower standard of proof mandated by Title IX are necessary to encourage victims to step forward.

Men counter that those accused of rape shouldn’t lose their rights when they step on a college campus, and that innocent defendants have been railroaded by kangaroo courts in which they’re not allowed to have a lawyer or, in some cases, to present their full defense.

DeVos referred to the bizarre case of a USC football player expelled for abusing his girlfriend even though she insists there was no abuse. This followed the news that the rape defendant in the notorious 2015 “mattress case” in which his alleged victim carried her mattress around campus and to her commencement ceremony had earned a measure of vindication earlier this year when the university paid him to settle his lawsuit and issued a statement declaring that, after years of being publicly rape-shamed in international media, he had done nothing wrong after all.

Like students at colleges and universities across the United States, I was stunned to learn that college campuses are sort of like Native American reservations: zones where the law applies theoretically but in practice is systematically ignored or enforced at significant variance to the way things go in the outside world.

The shooting of a motorist on a city street off campus by a University of Cincinnati police officer highlighted the fact that two out of three colleges have armed police forces — and that some of these campus cops are told they have the right to arrest, and even shoot, non-students in surrounding neighborhoods.

At least today’s colleges aren’t brazenly stealing land from public parks, as Columbia did in 1968 when it began construction on a gym in Manhattan’s Morningside Park. (The land grab sparked a riot and iconic student takeover of campus.)

The debunking of that big Rolling Stone piece about a supposed rape at UVA aside, it doesn’t take a statistician to grok that college campuses, with their witches’ brew of young people out on their own for the first time, minimal adult supervision and free-flowing booze set the stage for date rape as well as sexual encounters where consent appears ambiguous. The question is: should college administrators substitute for cops and district attorneys in the search for justice? Emily Yoffe’s Atlantic series on DeVos’ proposal strongly suggests no.

Yoffe portrays a system that encourages males to feel victimized by being considered guilty until proven innocent. “To ensure the safety of alleged victims of sexual assault,” she writes, “the federal government requires ‘interim measures’ —accommodations that administrators must offer the complainant before any finding of responsibility, including steps to ensure that she never has to encounter the accused… Common interim measures include moving the accused from his dormitory, limiting the places he can go on campus, forcing him to change classes, and barring him from activities. On small campuses, this can mean his life is completely circumscribed. Sometimes he is banned from campus altogether while awaiting the results of an investigation.” This is an injustice, and saying it’s necessary in order to protect victims doesn’t change that.

The New York Times recently published an op-ed that embodied the glib view of defendants’ rights au courant on college campuses. “Of course, being accused of sexual assault hurts,” wrote Nicole Bedera and Miriam Gleckman-Krut. “And there are things that we can and should do to help accused students — namely, providing them with psychological counsel.” Seriously? Men accused of rape face expulsion, felony charges (schools can refer cases to the police) and blackballing from other colleges if they apply. They need more than therapy.

It’s easy to see why colleges, and many parents of students, want to maintain their personal on-campus legal systems outside the bounds of adult law and order. 18-year-olds are legally adults but psychologically still kids, the thinking goes. Sending even serious matters like rape charges to the police can seem like a second brutalization of victims, and perhaps even unnecessarily harsh to the accused who, if innocent, may be able to assuage doubts with a simple explanation of their actions to friendly university staff members.

Though largely well-intentioned, and despite the fact that it is opposed by the despicable Donald Trump, this Title IX-based paternalism has no place in a society that purports to respect the concept of equal justice under the law. If there’s an alleged crime on a campus, students should call the cops.

The answer to nonresponsive police who disrespect victims isn’t to truncate defendants’ rights under a parallel facsimile of jurisprudence. The solution is to reform the police and the courts so that victims aren’t traumatized all over again. Let law enforcement do its job, and let educators do theirs.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall) is author of “Trump: A Graphic Biography,” an examination of the life of the Republican presidential nominee in comics form. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

SYNDICATED COLUMN: L.A. Times Lawyer to Court: “This is Not a Case About Quote/Unquote Truth”

Every defendant is entitled to a vigorous defense. That’s a basic principle of Western jurisprudence.

My belief in that precept was sorely tested by oral arguments in my defamation and wrongful termination case against The Los Angeles Times. It’s one thing for a lawyer to represent a distasteful client like the Times, whose crooked top management sold out its readers to the Los Angeles Police Department in a secret backroom deal. But when framing facts turns into outright lying in court, count me out.

I have great new lawyers. On July 14th, however, I was “between lawyers” because my previous ones had just dumped me and the scorched-earth Times defense team refused to grant me a delay so my new attorneys could get up to speed. So I was forced to represent myself pro se against a senior partner with three decades of experience as a courtroom litigator.

“Since the beginning of this case,” I opened, “the defense has tried to make this a complicated case about technicalities. In fact, it’s actually a very simple case.”

I went on to explain how, after a spotless six-year record as the paper’s cartoonist, the Times received a static-filled audio recording of unknown provenance from LAPD Chief Charlie Beck. Beck claimed the CD-R showed I’d lied in a blog post when I wrote that I was mistreated by a LAPD cop who’d arrested me for jaywalking.

I continued: “In fact, the audio did not show anything of the kind. In fact, the audio was obviously never listened to, because if they had, even if nothing else had happened, they would have been able to, in a quiet room with headphones, they would have been able to hear people arguing with the police officer. They would have heard phrases along the lines of, ‘Take them off. Take off his handcuffs,’ that sort of thing. The Times rushed to judgment. They operated extremely recklessly, negligently. They did not investigate the audio. They did not give me any benefit of the doubt whatsoever even though the doubt was 100 percent.”

Times lawyer Kelli Sager was unimpressed.

She is paid to be unimpressed.

“So Mr. Rall has repeated a lot of the stuff that’s in the [filing] papers. But as we said in our reply [motion] and as the court ruled on the individual defendants’ motion already, this is not a case about, quote/unquote, ‘truth.’”

Um…what?

I am so naïve. We were in a courtroom. If the truth — sorry, the quote/unquote ‘truth’ — doesn’t matter in a court, what does?

The Times’ answer: technicalities. Bear in mind, the Times is a newspaper. Their job is to print the truth.

“That’s not the argument that we made in the SLAPP motion [stet], whether or not the statements that he’s complaining about were true or not,” Sager continued. “The Fair Report Privilege doesn’t need the court to adjudicate the truth. The Fair Report Privilege looks at whether the gist and sting of what the articles reported were from records of the LAPD statements made by people in the LAPD that were official statements and so forth.”

Translation of the Times’ defense: It doesn’t matter if the Times published lies and refused to retract. Under California’s anti-SLAPP law — which is abused by deep-pocketed corporations so they can libel poor individuals with impunity — the Times can write whatever it wants as long as it generalizes about something a policeman said in a police record. This, of course, ignores the existence of defamation and libel statutes.

Sager went on: “Whether the Times had a good motive or bad motive is irrelevant under the law.”

Not really. The Times claims that I am a public figure. If the court agrees, Sullivan v. New York Times, the 1964 case that redefined defamation law, would be pertinent: “The Court held that the First Amendment protects the publication of all statements, even false ones, about the conduct of public officials except when statements are made with actual malice (with knowledge that they are false or in reckless disregard of their truth or falsity).” When the Times published its two pieces about me, they knew that what they were publishing (that their audio showed I was a liar) was false and they didn’t care. Motive matters.

Oh, the lies! Like when Sager said: “So there is no dispute that the records came from the LAPD.”

An hour earlier, in the same hearing, in front of Sager, I had said:

“I dispute that these records were officially released by the LAPD. There is a declaration by the investigative reporter Greg Palast in that giant pile of paper next to you in which he says that he contacted the public information office of the LAPD and in no uncertain terms they denied ever having released the documents and the audio. And in fact, that they’re still in the evidence room over at the LAPD. So what we have here is a case of conflation; a cases of many lies of omission, some lies of commission. But one of the big lies of omission is that the L.A. Times is trying to pretend that Chief Beck is the LAPD. And that is no more true than President Trump is the United States government. The official records have never been released.”

How could she say there was no dispute?

Sager couldn’t argue the facts. So she pretended the facts didn’t exist.

You can read the whole transcript here.

You can support my fight for free speech here.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall) is author of “Trump: A Graphic Biography,” an examination of the life of the Republican presidential nominee in comics form. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

SYNDICATED COLUMN: What Happened When I Represented Myself as My Own Lawyer

For a cartoonist, I turned out to be a fairly decent lawyer. But I didn’t want to represent myself. It took two vicious lawyers to force me into that position.

One of those lawyers was mine.

I’m suing the Times because they repeatedly, knowingly and intentionally defamed me after firing me as a favor to LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, a thin-skinned pol I’d criticized in my editorial cartoons. The paper responded by turning California’s “anti-SLAPP” law, designed to protect people like me against corporations like the Times and its parent company Tronc, on its head; this $400 million corporation is accusing me — a five-figure income cartoonist — of oppressing its First Amendment rights by using my vast wealth to intimidate them.

Before my case is allowed to begin in earnest, anti-SLAPP requires a plaintiff (me) to convince a judge that, if everything I allege in my lawsuit turns out to be true, I’d likely win before a trial jury. But anti-SLAPP is as confusing as French grammar, so many judges interpret the law much more harshly than it’s actually written.

All the lawyers I talked to told me that I’d almost certainly win at trial if my case survived anti-SLAPP and made it to a jury. Ironically, getting past anti-SLAPP would be our toughest challenge.

The lawyer who took my case agreed with this assessment. But when oral arguments for the first of the Times’ three anti-SLAPPs against me took place on June 21st in LA Superior Court, his firm inexplicably assigned a junior associate, Class of 2013, to take on Kelli Sager.

Kelli Sager, who represents the Times, is a high-powered attorney with more than three decades of courtroom experience, a senior partner at Davis Tremaine Wright, an international law firm that represents giant corporations.

I liked my junior associate. She’s smart and may someday become a great lawyer. But she was no match for a shark like Kelli Sager. Sager talked over her. My lawyer let Sager get away with one brazen lie after another, either too unprepared or timid to respond. She couldn’t even answer the judge’s simple question to walk him through what happened to prompt my lawsuit.

It was a rout. Sager was eloquent and aggressive. My lawyer couldn’t begin to articulate my case, much less sway the judge. I lost that round.

Determined not to lose the all-important important hearing number two, against the Times and Tronc, I asked my law firm to meet for a strategy session. Bafflingly, they refused to confer or to send a more senior litigator to the next one. Another defeat was guaranteed.

Then my firm fired me — days before that key anti-SLAPP hearing. I had no idea that was even a thing, that that could happen.

I swear — it wasn’t me. I was professional and polite every step of the way. I have no idea why they left me hanging.

Normally in such situations, legal experts told me, the court grants a “continuance,” legalese for a delay, to give me time to look for a new attorney and allow him or her to familiarize themselves with the case. But it helps a lot if the opposing side says they’re OK with it.

A continuance is typically freely granted, even during the most ferocious legal battles. After all, you might be the one with a family emergency or whatever next time.

But Kelli Sager smelled blood. Figuring I’d be easier to defeat without legal representation, she fought ferociously against my requests for a continuance. Thus came about the following absurdity:

I found a new lawyer. But he needed a few weeks to get up to speed. True to her standard scorched-earth approach to litigation, Sager refused to grant me the courtesy of a continuance. So I was forced to rep myself in pro per (that’s what they call pro se in California) on July 14th.

My heart was pounding as I approached the plaintiff’s table, standing parallel to Sager. And I’m an experienced speaker! I’ve held my own on FoxNews. I’ve spoken to audiences of hundreds of people. I’ve hosted talk-radio shows. Yet dropping dead of a heart attack felt like a real possibility. I can’t imagine what this would feel like for someone unaccustomed to arguing in public.

The judge asked me to proceed. I nervously worked from prepared notes, explaining why my case wasn’t a “SLAPP” (a frivolous lawsuit I didn’t intend to win, filed just to harass the Times), that the anti-SLAPP law didn’t apply. I attacked the Times’ argument that their libelous articles were “privileged” (allowed) under anti-SLAPP because they were merely “reporting” on “official police records” about my 2001 jaywalking arrest.

If they’d been “reporting,” the articles would have had to follow the Times’ Ethical Guidelines, which ban anonymous sources, require careful analysis of evidence and calling subjects of criticism for comment. They didn’t come close. These weren’t news stories or even opinion pieces; they were hit jobs.

I explained that the records weren’t official at all, the LAPD denied releasing Beck’s unprovenanced audio, which differed from the official one at LAPD HQ. Much of the discussion was about legal minutiae rather than the broad strokes of what my case is about: I wrote a blog for latimes.com, the Times edited it and posted it, Chief Beck gave the Times a blank audio they said showed I’d lied about what I wrote, I had the audio cleaned up and it showed I’d told the truth, rather than issue a retraction when they found out they were wrong the Times refused to change their behavior and continued to insist I’d lied.

There’s also the big picture: if a newspaper’s parent company sells its stock to the police, and that newspaper’s publisher is a crony of the police chief who accepts awards from the police union, how can readers trust that newspaper not to suppress criticism of the police? Do Black Lives really Matter if investigations of police brutality don’t always make it to print, if writers and cartoonists have learned they can get fired and libeled if they annoy the cops?

I will soon receive a transcript of the hearing. I will post it at Rall.com.

Sager’s counterargument boiled down to: newspapers can publish anything they want, even lies, because the First Amendment protects free speech — as if libel and defamation law don’t exist.

Her defense for the Times was not that I lied. The audio makes clear that I didn’t. Her defense, the defense for a newspaper, was that the truth doesn’t matter.

Arguments ran over two hours.

On June 21st the judge ruled against my erstwhile lawyer directly from the bench.

On July 14th, I at least gave the judge something to think about. He took the matter “under consideration.”

I await his decision.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall) is author of “Trump: A Graphic Biography,” an examination of the life of the Republican presidential nominee in comics form. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

Breaking Modern Essay: How One Speeding Ticket Can Ruin Your Life

This essay originally appeared at BreakingModern.com:

There once was a time during the 1980s when you could find a parking ticket on your windshield, crumple it up and drive off as if it had never existed. Nothing would happen. Usually. It was worth the risk.

But that time is no more.

I am often asked, to my considerable surprise, by seemingly intelligent people — people who don’t eat their own boogers, people who are capable of holding gainful employment — whether they can blow off and get away with a ticket.

My answer? NO! You cannot!

There are three relatively recent reforms in how municipalities handle petty offenses which make ignoring a parking or desk-appearance ticket (more on this later) a Bad Idea. They include rapidly escalating costs (for example, $75 if you pay within 10 days, $120 within 20 days, $200 within 30, and so on). There now are computer-linked “reciprocity” systems between cities and states (if you get a ticket while driving a rental car in California, they’ll know it was you — and you get slammed with a fine and points on your license back home in Texas). And they also include computer-issued arrest warrants if you fail to pay or appear in court.

You won’t even know they’re looking for you until a cop stops you for something else down the road and runs your ID. Then it’s all over. And it gets worse …

Beer, Bench Warrant and Busted!

“A single beer put Patrick Lamson-Hall behind bars for 27 hours,” reported The New York Daily News. “The New York University grad student was slapped with a summons and a court date for drinking a can of Pabst Blue Ribbon on a West Village stoop.”

Turns out the 25-year-old Oregon native forgot about both until a pair of cops stopped him — it was months later — for riding his bike on a Brooklyn sidewalk. Within minutes, Lamson-Hall was placed in handcuffs, tossed into a squad car and taken to the 79th Precinct in Bedford-Stuyvesant. He was busted on a bench warrant over his failure to appear in court.

“I assumed they’d have me pay a ticket for the open container,’ said Lamson-Hall afterward. ‘It didn’t occur to me that I was going to spend the night in jail.’”

Lamson-Hall’s experience is hardly rare. One million New Yorkers — that’s one out of eight city residents — have outstanding warrants for similar “desk-appearance tickets” for offenses like littering or failing to clean their dog’s poo. The vast majority probably have no idea the cops are looking for them.

“Even if you feel that you were in the right, even if you feel that the summons is ridiculous, you need to come to court to resolve it because there are real consequences if you don’t,” says David Bookstaver, a spokesman for New York’s court system. Which brings us to:

The Opposite of Bliss

A parking ticket, a moving violation like a speeding ticket or a desk-appearance ticket for a petty crime (like, soon in New York City, for smoking pot on the street), make sure you make that ticket a top priority in your life.

Ignoring tickets has quite literally ruined countless lives. Some people have even lost their cars and become homeless as a result.

Like in the movie The Terminator, the justice system will not stop, ever, until you pay, show up, or get exonerated.

Put that ticket on your fridge. Read it carefully. Deal with it first thing.

Do You Need to Show Up? Probably, Yeah

There are two kinds of tickets: those that require you to show up in court and those that can be mailed in. Generally, bigger offenses, like driving 20 mph or faster above the speed limit, do require a court appearance. Minor ones, not so much. So read your ticket carefully to see if you need to show up.

If you have a scheduled court date, but can’t make it, you can usually have the date postponed. Call the court or check their website to learn the procedure for requesting a delay, or “continuance.” Living far away isn’t an excuse not to attend. I once had to fly from New York to central Nevada to attend to a speeding violation. This sucked. But it was what it was.

Before we continue with what to do when you get a ticket, however, let’s go back to something you should know before you get one:

Rule Zero: Shut Up! This Cop is Not Your Friend

Citizens and residents of the United States — and tourists, too— have the right not to incriminate themselves. When a cop confronts or pulls you over, he or she is trained to try to get you to incriminate yourself. When a policeman asks: “Do you know how fast you were going?” or “Do you know why I pulled you over?” he or she wants you to admit you were speeding or whatever.

The authorities will use your casual comments and answers in court if you decide to challenge your ticket.

So say nothing. The truth is, you don’t even know why you were stopped. How could you? You don’t know how fast you were going. Speedometers aren’t precise; you can’t read the officer’s mind. Shut up. Use non-committal answers, like “I see.” If asked how fast you think you were going, feel free to claim you were going the legal limit. It’s not even illegal to lie to a cop in this situation and it sure can’t hurt.

Be polite. Keep your interior lights on and your hands on the wheel to avoid freaking out the officer. There’s no point arguing. If the cop asks you whether he or she may “just take a look” inside your vehicle, your answer should always, always be no.

Even if your car is clean, there is no advantage — none, nada — to cooperating.

Be nice. Sometimes that makes all the difference.

Okay, as you were:

Should You Just Pay the Fine?

It’s tempting to send in your check and be done with it. Assuming you pay on time, the court will be satisfied. Regardless, if you decide to do this, be careful. I once got arrested on a desk warrant after Long Island Expressway police failed to credit me for payment for a speeding violation. Now I carry copies of my canceled checks in the glove compartment along with my auto registration! Live and learn.

Parking tickets should be paid promptly in order to avoid escalating fines or even nastier sanctions such as getting your car towed away or clamped by “the Denver boot.” Parking fines are typically relatively low, so it may not be worth it to take time off from your job or to hire a lawyer to try to get them reduced or thrown out.

What if You Really Are Innocent?

Well, that’s an exception. It happens. I got a parking ticket once in Washington, D.C. Neither I nor my car were even there at the time, however. I appealed by mail, presenting proof I was in New York that day and that the model of car wasn’t mine. (The traffic agent probably miswrote the license plate number.) But whatever. I won.

Why You Going to Court is Your Best Chance of Getting Off

If you’ve got several previous tickets and the time to spare, you can get real money knocked off by dressing decently and spending an hour or two in court. I recently got tickets totaling $240 for parking down to $100 just by showing up and explaining that I was confused by new parking regulations.

If you can afford it, moving violations should always be challenged in court, ideally by hiring a lawyer who specializes in traffic tickets in the relevant municipality. Mail appeals tend to be less successful. That’s because the days of getting a speeding ticket, paying it off and forgetting about it are long gone.

Worse, most states now have quietly passed draconian penalties for moving violations i.e. New York State’s “Driver Responsibility Assessment Law.” What this means is that you don’t just pay the fine listed on the ticket. Instead, you pay hundreds of dollars more, even if your license is from another state!

In Virginia, perhaps the most notorious state for this in the Union, speeding is often charged as “reckless driving,” punishable by a year in prison and a $2,500 fine, not to mention a criminal record that’ll follow you mercilessly for the rest of your miserable life.

And then the extra bill arrives in the mail, often months after you plead guilty.

It Doesn’t Take Much to Get Your License Suspended. Get a Lawyer

These days, it doesn’t take much to get your license suspended. In New York, for example, a speeding violation of 20 mph or higher over the limit — say, 76 in a 55 — gets you six points on your license. If you get a second six-point violation within 18 months, they take away your driving privileges. And some auto insurers will jack up your premiums to reflect your need for speed.

In the long run, a lawyer will be cheaper than trusting your fate to the tender mercies of the judiciary.

Most lawyers will charge you less to represent you than you’d pay in fines in the aggregate. You won’t have to show up in court, which means saved personal days.

How can a lawyer help you after you’ve been nabbed with a ticket for something you actually are guilty of? Easy. Lawyers use several tricks to reduce your exposure. They may negotiate your ticket down to a minor offense, like a parking violation, that carries a lesser fine and/or no points. They might schedule your court hearing for a time when your police officer is on vacation, ensuring your case gets thrown out. (That trick, a relic from the old days, still works. Waiting for the cop to not appear in court.)

Or they repeatedly plead for a continuance until the 18-month period when you’re just one ticket away from suspension passes (the clock starts ticking on the day of the alleged offense).

Can’t Afford a Lawyer? How to Act Like One …

If you can’t afford a lawyer — I advise you to beg, steal or borrow to pay one, but anyway — use the lawyerly trick of delaying your court date as long as possible. After your delays run out, show up in court yourself; some judges will reward your deference.

Ask if you can take traffic school to get your points eliminated.

And for God’s sake, drive cautiously. Don’t get another ticket until the passage of 18 months erases the points on your driving record.

Similarly, a desk-appearance ticket is a serious matter. If you’re found guilty, you could wind up with a misdemeanor — yes, a real criminal record! Again, if you have the money, hire a lawyer to work his or her magic. If you’re broke, show up. If you lose, pay right away.

What Happens if You Don’t Pay?

This is not an option. Stop thinking like that! You are going to pay. The only question is when — now or later — and how much — a little or a lot.

Pay later, and you will pay a lot.

This is NOT one of those happy aspects of life that rewards procrastination.

If your failure to appear in court results in your arrest, you could be in for a singularly unpleasant experience, one that could even cost you your job or your life. A former roommate of mine got busted buying a small quantity of pot from an undercover narcotics agent in lower Manhattan. It was noon; he was at lunch. When he wasn’t back at his desk at 1 p.m., his boss was worried. When he didn’t show up for three days (long waits to be processed through the system aren’t rare, especially when there’s a holiday), he became angry — and he fired him.

Then there’s the public beer/bike on the sidewalk guy I mentioned up top. He spent a night in jail — one night in a solitary jail cell with no windows, no water and a broken toilet. Cops refused to let him make a phone call before vanishing for hours.

You Probably Won’t Get Beaten Up in Lock-Up, But …

Yeah. I know. The Constitution is there to protect you. But in the real world, the Constitution often ends the second handcuffs hit your wrists. You’re probably not going to get raped or beaten in the lock-up, but if you need your meds to stay healthy — an asthma inhaler, say — you’re in deep doo doo if they throw you in jail. Standard procedure is to confiscate your drugs and ignore you when you complain.

This can kill people. Not that all authorities care. It’s procedure, like I said.

Even if the state doesn’t get all medieval on you, fines for non-payment are going to pile up exponentially. And thanks to sophisticated license-plate scanning machines that collect hundreds of millions of images per year for collection into a national database out of George Orwell’s worst nightmares, it’s only a matter of time before you get stopped and arrested … or have your car confiscated.

It ain’t fair. It ain’t right. But when you get a ticket, the last thing you want to do is ignore it.