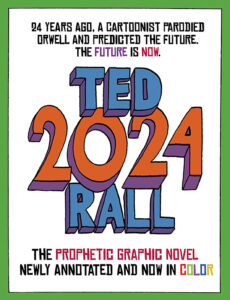

Twenty-four years ago, I wrote and published my “Nineteen Eighty-Four” update/parody “2024,” a graphic novel about a dystopian future of our own making. The book contained my predictions about what 2024 would look like—and guess what? I was mostly right: rather than be oppressed by an intrusive security state (which we have), the real danger to human individuality would come from our personal electronic devices. (And also wrong about some stuff.)

Twenty-four years ago, I wrote and published my “Nineteen Eighty-Four” update/parody “2024,” a graphic novel about a dystopian future of our own making. The book contained my predictions about what 2024 would look like—and guess what? I was mostly right: rather than be oppressed by an intrusive security state (which we have), the real danger to human individuality would come from our personal electronic devices. (And also wrong about some stuff.)

Now that it’s actually 2024, I thought it would be fun to revisit those predictions, which is how “2024: Revisited” was born.

“2024: Revisited” adds:

- Beautiful Full-Color artwork (originally, it was black and white)

- Annotations explaining references and inspirations

- A lengthy new Foreword by yours truly.

N.B.: The link is currently only for the Kindle eBook edition. Later this week, the print edition will become available. Watch this space if, like me, you prefer paper.

Historians and archivists call our times the “

Historians and archivists call our times the “ The Times doesn’t have many pieces I want to read anymore.

The Times doesn’t have many pieces I want to read anymore.  So, today I read The Times in a slow-down-to-check-out-the-car-wreck way. And I came across an item that brought home the widening cultural class divide. Here it is:

So, today I read The Times in a slow-down-to-check-out-the-car-wreck way. And I came across an item that brought home the widening cultural class divide. Here it is: Alter continues, “There are no airport maps or disheartening lists of in-flight meals and entertainment options in

Alter continues, “There are no airport maps or disheartening lists of in-flight meals and entertainment options in  Purveyors of literary fiction sometimes wonder aloud why their non-genre genre

Purveyors of literary fiction sometimes wonder aloud why their non-genre genre