Maybe it’s time to change the flag on your social-media avatar.

To the extent that objective guideposts exist in international relations, the United States has no legal obligation to defend Ukraine. Ukraine, a U.S. strategic partner, is neither an ally nor a member of NATO. Nor is it in our neighborhood. Much as the Monroe Doctrine declares the entire Western hemisphere under American sway, Russia has long declared all the former Soviet republics, including Ukraine, to belong to its “sphere of privileged interest.”

Despite our newfound obsession with a nation two out of three Americans couldn’t find on a map last month, American journalists and ordinary citizens have been so moved by scenes of death and destruction that members of both major parties have quickly come together to declare that they #StandWithUkraine, want to welcome Ukrainian war refugees, favor sending advanced weapons to aid Ukraine in its defense and support an array of harsh sanctions against Russia so wide-reaching that they ban Russian opera singers, paralympians and cats.

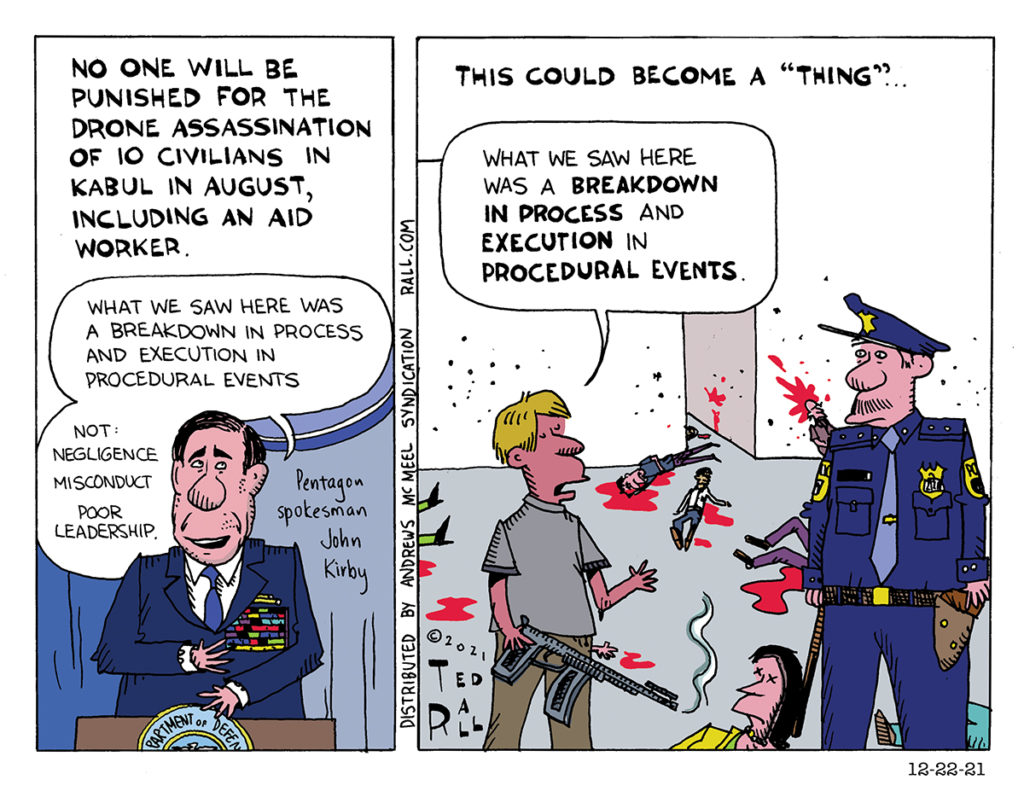

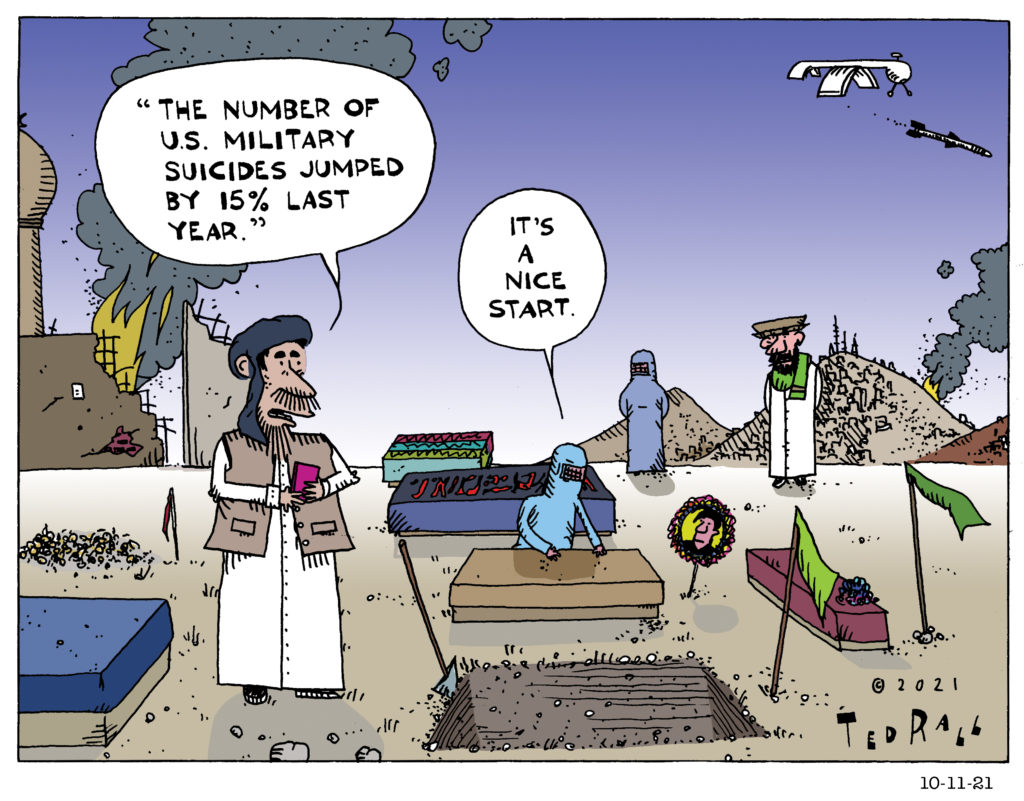

Headlines aside, Ukraine is not the most miserable place on earth right now. And the cruelest inflictor of human pain isn’t Russia.

It’s the United States.

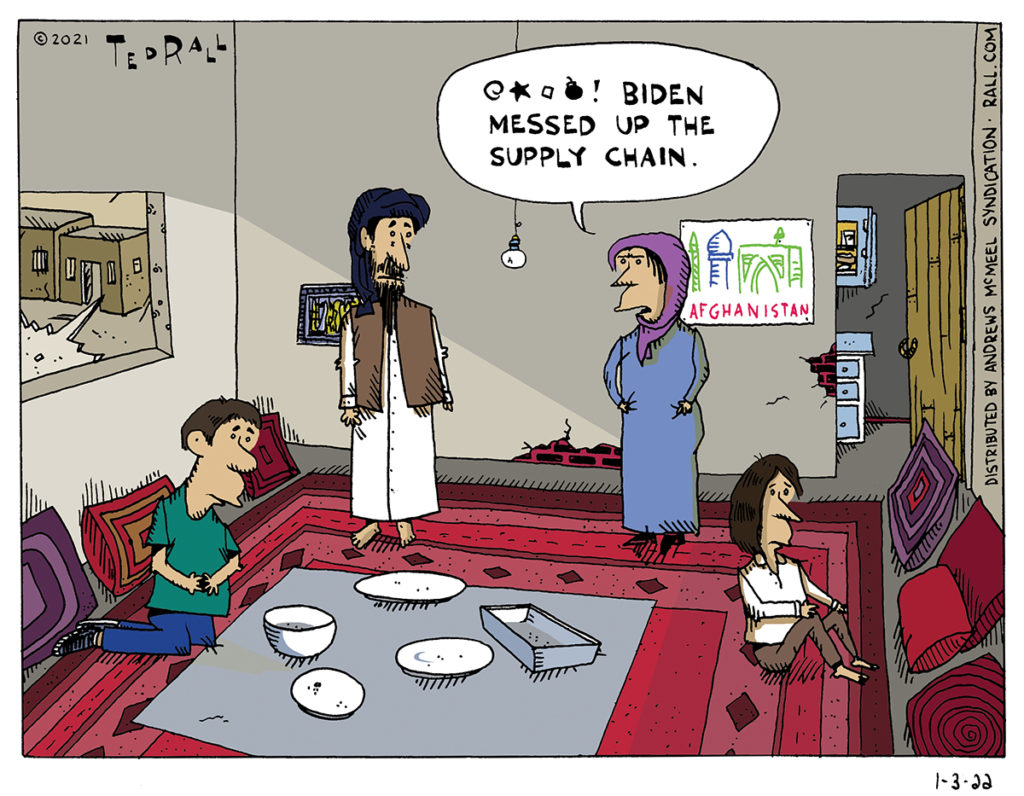

“Afghanistan has become the world’s largest humanitarian crisis,” Jane Ferguson reported in The New Yorker in January. “More than 20 million people are on the brink of famine.”

“Afghanistan,” says the U.N. World Food Program, “teeters on the brink of universal poverty. As much as 97% of the population is at risk of sinking below the poverty line.”

The afghani, the national currency, has lost 30% of value since the American withdrawal last August—a collapse so precipitous that the U.N. worries that a liquidity crisis is imminent. Money exchanges in major Afghan cities have ceased operations, portending a return to the cashless subsistence economy, based on barter, that prevailed before the 2001 U.S. invasion, when Afghanistan was officially designated a failed state. Imports, which make up a high percentage of consumer goods, have been soaring in price as unemployment has shot up following the cessation of international aid that accounted for more than 40% of GDP. UNICEF warns that up to one million children under age five may die from malnutrition and lack of essential services by the end of 2022.

Schoolchildren are taught outside in the snow because schools can’t afford electricity for lights. Desperate Afghans are selling daughters and their own kidneys (going rate $1500) to survive.

“U.S. politicians and media frequently treat Afghanistan these days like a TV series that had its finale in 2021,” observes James Downie of The Washington Post. “But Afghans’ suffering is very much ongoing, and American decisions continue to make it worse.” With all eyes on Ukraine, no one is paying attention to the graver situation in Afghanistan—even though (or because?) the spiralizing disaster there is largely our fault.

1.4 million Ukrainian refugees have fled; 200,000 are internally displaced. Compare that to Afghanistan: 2.2 million Afghans have gone to neighboring countries in the last six months and 3.5 million are internally displaced.

Even if we don’t exactly care about the people of Afghanistan, what about self-interest? It’s curious strange that we’ve already forgotten that an unstable, impoverished Afghanistan can pose a danger to the region and the world.

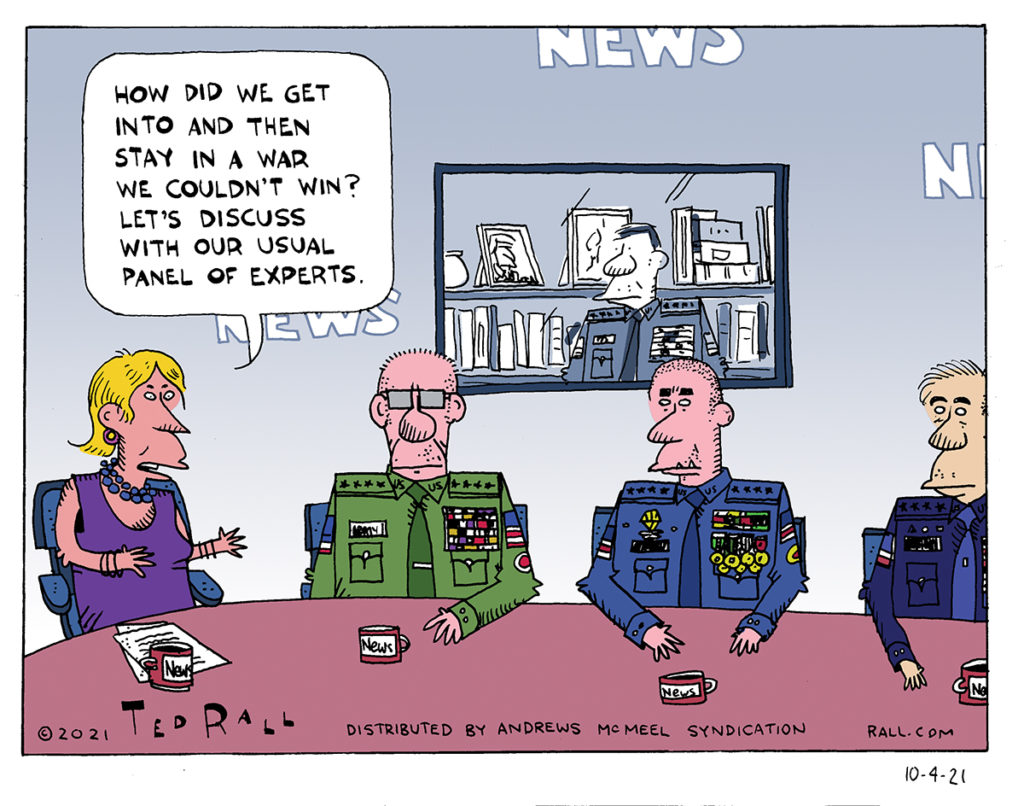

Downie notes: “That famine is a direct consequence of the United States’ failure to create a self-sustaining economy there over two decades.” During the occupation we created a kleptocracy by dumping billions of dollars on pallets of shrink-wrapped $100 bills into the hands of corrupt government officials, connected oligarchs and warlords while small entrepreneurs were shaken down for protection money. “The biggest source of corruption in Afghanistan,” an American official told The New York Times, “was the United States.”

Coverage of the Afghans’ plight, such as it is, focuses on the $7 billion to $9.5 billion held by the former Afghanistan government in U.S. banks, now frozen by the Biden Administration, which stubbornly refuses to recognize the reality of Taliban rule.

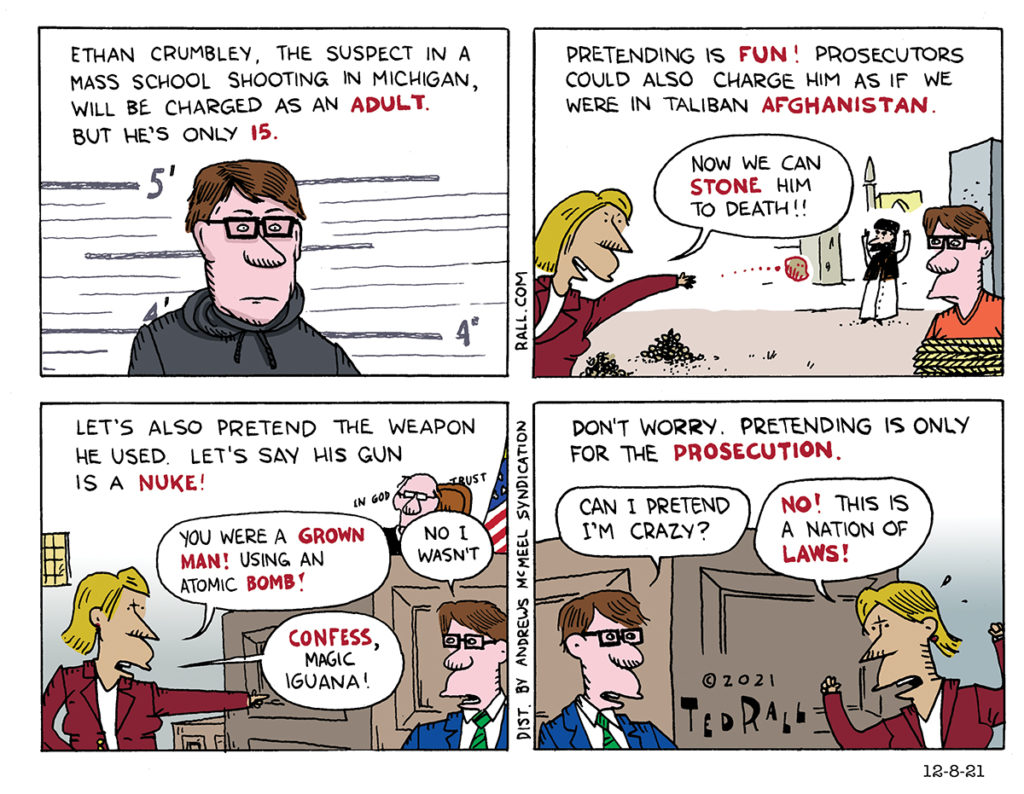

Biden wants to siphon off $3.5 billion of the Afghan funds to settle legal claims by the families of 9/11 victims, a bizarre stance given the fact that no Afghan national had anything to do with the terrorist attacks. The remaining monies, says the president, will only be released to the Taliban after they allow girls to attend school, guarantee universal human rights, form an inclusive government and promise to sever all ties with terrorist groups.

The Taliban say they’re open to negotiations, but none have been scheduled.

While the White House dithers, babies are starving to death in Afghan hospitals without medicine.

Biden’s statements border on fantasy. “[The money] is not going to the Taliban; it is going to be used for the benefit of the Afghan people,” an anonymous White House official told the Post. The U.S. government couldn’t control the fate of aid money to Afghanistan while occupying with tens of thousands of soldiers. Now we’re gone, without a single embassy or consulate in the whole country.

Like it or not, the Taliban is the government of Afghanistan. They will rule the country for the foreseeable future. There is no realistic way to help the Afghan people without recognizing their government, lifting sanctions and restoring the flow of aid money.

Now, in the middle of an especially harsh winter in a mountainous country whose meager agricultural operations are disproportionately impacted by climate change, there is no time to lose. The U.S. should offer a helping hand immediately, without preconditions.

Give Afghanistan its money back.

We can set deadlines for the Taliban to meet U.S. benchmarks on women’s rights and other issues, stating that non-compliance will mean there will be no resumption of aid.

Even if the Taliban spend its billions carefully, it won’t last long in a country of 40 million people. Over the coming years, the U.S. has a moral obligation as well as a vested interest to help Taliban-ruled Afghanistan transition from a bloated welfare state dependent upon foreign aid to a modern, developing, independent economy.

Whether or not we relate more easily to blonde European Christians than darker-skinned Central Asian Muslims, back-burnering the U.S.-made catastrophe in Afghanistan in favor of the more telegenic mayhem in Ukraine is unconscionable.

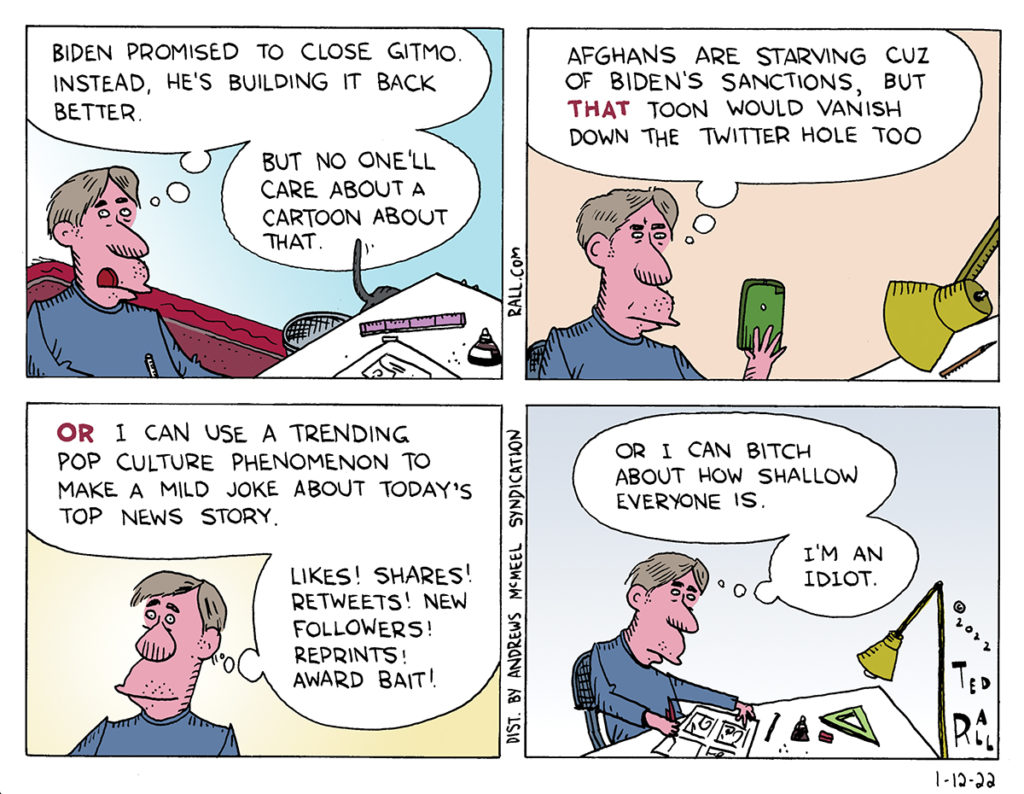

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)