“We know where they are,” Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said in March 2003 about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. “They’re in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad and east, west, south and north somewhat.” We found nothing. Rumsfeld knew nothing. A year after the invasion, most voters believed the Bush Administration had lied America into war.

At the core of that lie: certainty.

The 2002 run-up to war was marked by statements that characterized intelligence assessments as a slam dunk. “Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us,” Vice President Dick Cheney said in August 2002. “These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence,” Secretary of State Colin Powell told the UN.

Rumsfeld knew that if he said that Saddam probably had WMDs it wouldn’t have been enough. Americans required absolute certainty.

Imagine if the Bushies had deployed an honest sales pitch: “Though it is impossible to know for sure, we believe there’s a significant chance that Hussein illegally possesses weapons of mass destruction. Given the downside security risk and the indisputable fact that he is a vicious despot, we want to send in ground troops in order to remove him from power.” The war would still have been wrong. But our subsequent failure to find WMDs wouldn’t have tarnished Bush’s presidency and America’s international reputation. Trust in government wouldn’t have been further eroded.

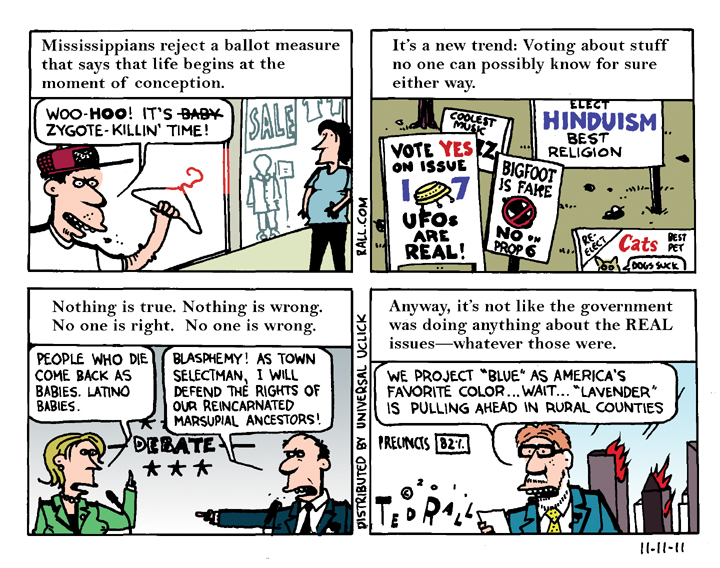

False certainty has continued to poison our politics.

Four months into Trump’s presidency 65% of Democratic voters didn’t believe he had won fairly or was legitimate. 71% of Republicans now say the same thing about Biden. What’s interesting is the declared certainty of Democrats who decry Trump Republicans’ “Big Lie.” Biden probably did win. But it’s hardly certain.

It is not popular to say so, but there is nothing unreasonable or insane or unpatriotic about questioning election results. From Samuel Tilden vs. Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 to Bush vs. Gore in 2000 many Americans have had good reason to wonder whether the winner really won. Only an omniscient deity could know for certain whether all 161 million ballots were counted correctly at all 132,556 polling places in the 2020 election.

Democracy requires faith. If evidence indicates that our faith is unwarranted it must be fully investigated; otherwise we must assume that official results are accurate.

The Republicans’ refusal to accept the official results is only slightly less justifiable than the Democrats’ overheated “Big Lie” meme.

“We have been far too easy on those who embrace or even simply tolerate this idea [that Trump was the true winner of the 2020 election], perhaps because it has completely taken over the Republican Party, and we still approach any question on which Republicans and Democrats disagree as though it must be given an evenhanded, both-sides treatment,” Washington Post columnist Paul Waldman wrote January 6th. “We have to treat those who claim Trump won in precisely the same way we do those who say the Earth is flat or that Hitler had some good ideas. They are not only deluded, they are either participating in, or at the very least directly enabling, an assault on our system of government with terrifying implications for the future. They are the United States’ enemies. And they have to be treated that way.”

Whoa. I am terrified of the slippery-slope implication that even talking about a topic is out of bounds. If mistrust of the competence and integrity of thousands of boards of elections and secretaries of state and public and private voting machines makes one a domestic enemy of the United States, what does that say about the 65% of Democrats and 71% of Republicans who doubted the results of the last two elections?

Why not just say that we think Biden won and there’s no reason to believe otherwise? It may be easier to shout down doubters than to make a well-reasoned argument but our laziness betrays insecurity.

Every day we make decisions based on uncertainty. The plane will probably land safely. The restaurant food probably isn’t poisoned. The dollar will probably retain most of its value. Why can’t Democrats like Waldman admit that election results are inherently uncertain? Republicans know it—at least they know it when the president is a Democrat—and Democratic arguments to the contrary of what is obviously true only serve to increase polarization and mutual mistrust.

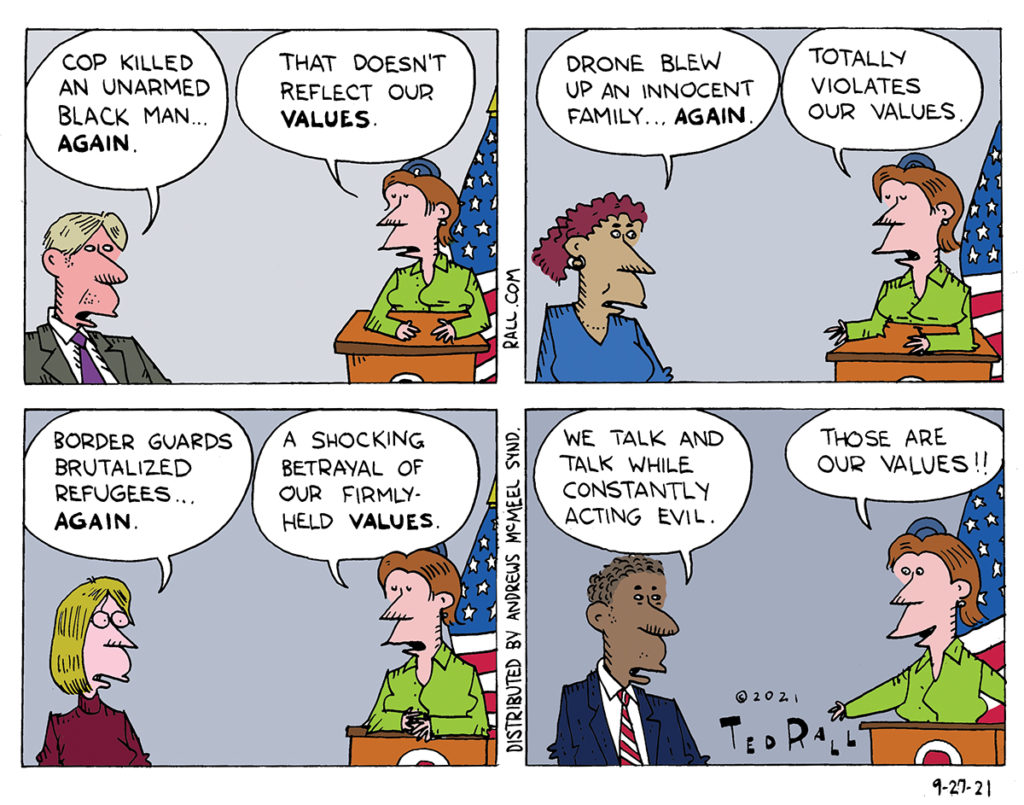

Vaccination and masking politics are made particularly venomous by rhetorical certainty that, given that science is constantly evolving and COVID keeps unleashing new surprises, cannot be intellectually justified. Those of us who have embraced masks and vaccines (like me) ought to adopt a humbler posture: I’m not an epidemiologist, I assume that scientists know what they are doing, I’m scared of getting sick so I’m following official guidance. Sometimes, as we know from history, official medical advice turns out to be mistaken. I’m making the best guess I can. Most of us are blindly feeling our way through this pandemic. We should say so.

We also need to express uncertainty about climate change. There is scientific consensus that the earth is warming rapidly, that human beings are responsible and that climate change represents an existential threat to humanity. I believe in the general principle. But it’s irresponsible and illogical to attribute specific incidents to climate change considering that extreme weather existed centuries before the industrial revolution. We will never reach climate change deniers by overreaching as when the Post described late December’s Colorado wildfires as “fueled by an extreme set of atmospheric conditions, intensified by climate change, and fanned by a violent windstorm.” Why not instead say “probably intensified” or “believed to have been intensified”?

Those of us who believe greenhouse gases are warming the planet should argue that, while nothing is ever 100% certain, it’s a high probability and, anyway, what’s wrong with reducing pollution? People who are certain that climate change isn’t real may be annoying, and given that the human race is at stake, perhaps dangerous. But the answer to incorrect certainty isn’t equal-and-opposite correct certainty.

It’s uncertainty.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the weekly DMZ America podcast with conservative fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

At worst, drone operators report being mind

At worst, drone operators report being mind