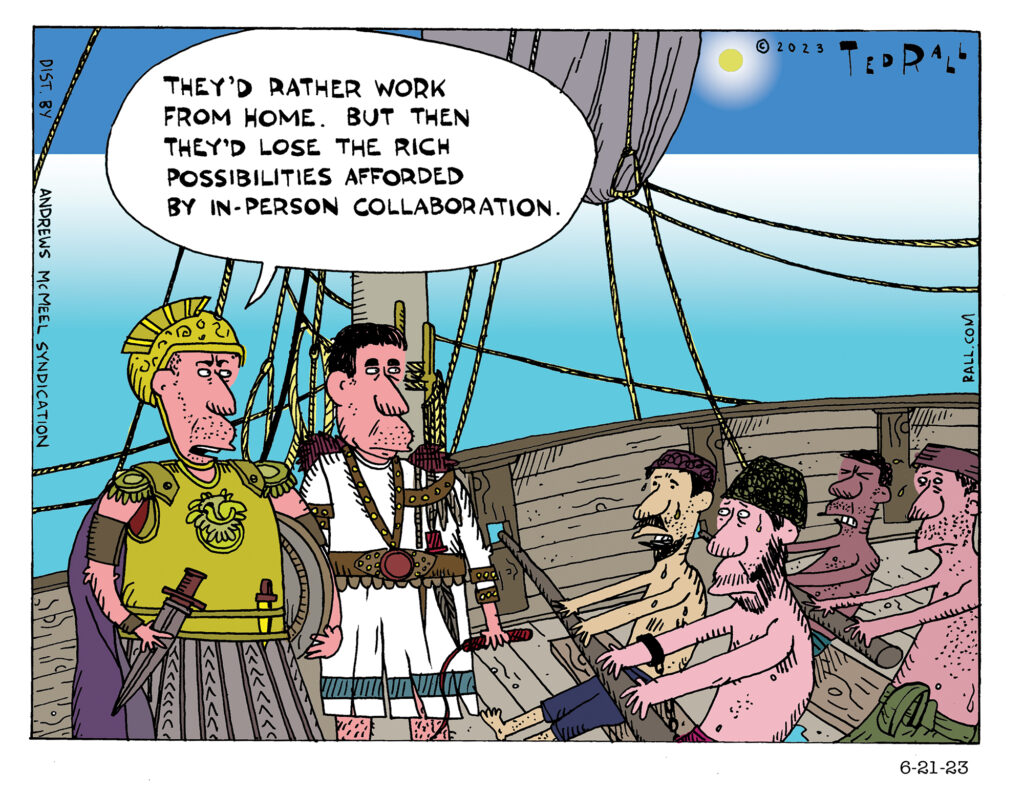

Many employers are increasingly upset that workers don’t want to return to offices or to endure long unpaid commutes from their homes. They keep talking about the possibilities for collaborating in person, ignoring the realities of open floorplans, in which stressed-out workers avoid one another under their headphones.

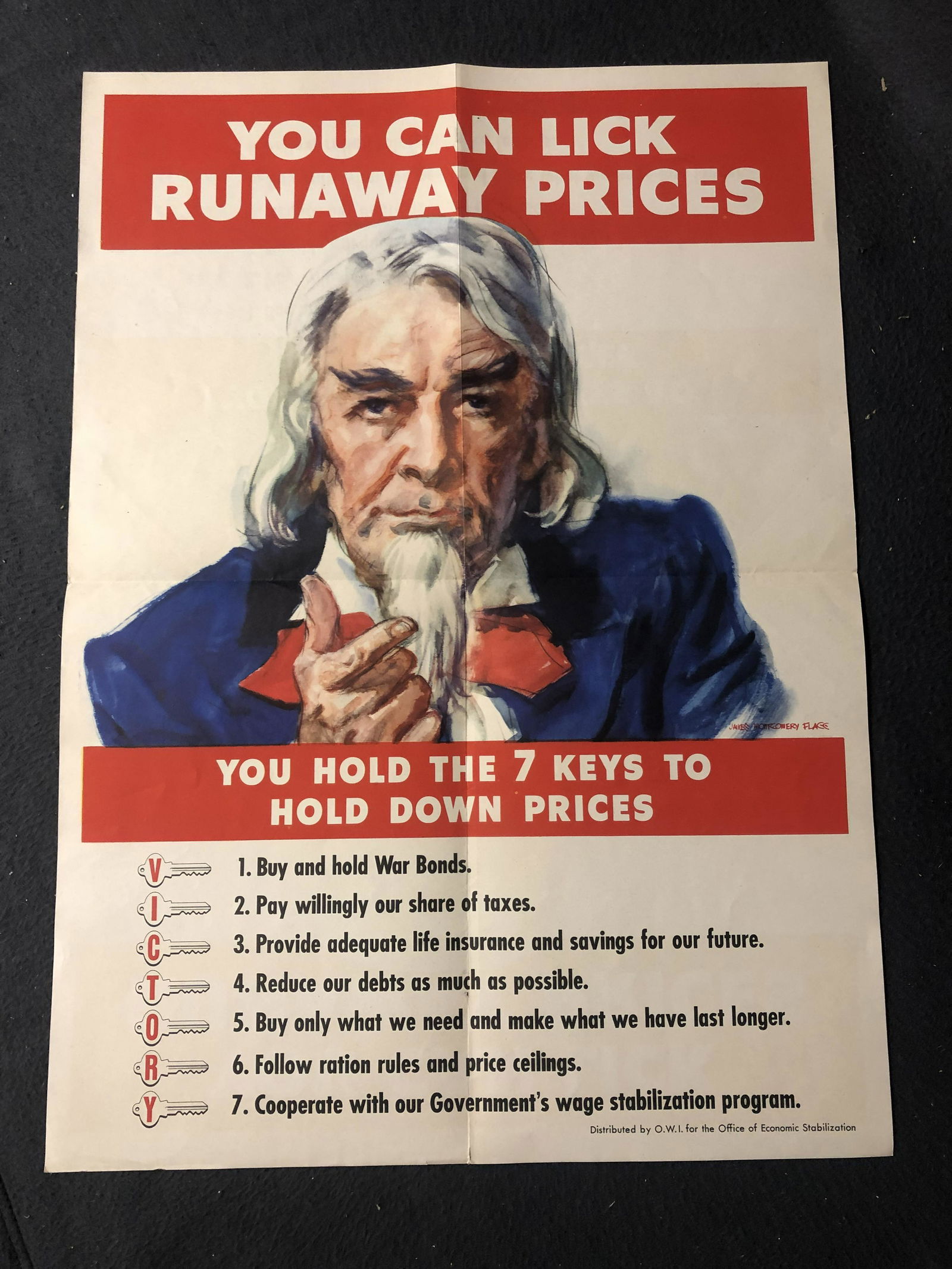

What’s Worse Than Inflation? Fighting Inflation.

Inflation is a cancer. It eats away at savings and consumer confidence. But the tools the United States government uses to fight inflation are often worse—they’re a form of chemotherapy that’s even more likely to kill the economy than the underlying disease. When your car is careening down a hill, slamming on the brakes is an inexperienced driver’s first instinct. But it’s the last thing you should do. Unfortunately, the history of inflation-fighting indicates that monetary policymakers seem to prefer crashes to soft landings.

Fueled in large part by massive deficit spending as the Pentagon tried to bomb its way to victory in the unwinnable Vietnam war, inflation ran rampant from the latter part of the presidency of Richard Nixon through that of his successor Gerald Ford, and infamously contributed to the destruction of Jimmy Carter’s reelection chances.

Inflation encourages consumer spending because, if you put off a purchase, it will cost more later. Enter Paul Volcker, appointed to the chairmanship of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1979. Determined to radically reduce spending and wages, he applied the anti-stimulus of sky-high Fed interest rates that peaked out at nearly 20% in 1981, Reagan’s first year in office. The result was two back-to-back recessions, which saw unemployment soar even higher than during the Great Recession of 2008-11.

Inflation was dead for the foreseeable future. With the benefit of hindsight, however, the cost of taming inflation was too damn high.

Reagan’s supply-side policies, which centered around tax cuts for large corporations and wealthy individuals coupled with austerity for everyone else, combined with Volcker’s hard line on inflation to create an anemic mid-1980s recovery before the 1987 stock market crash marked the start of yet another Republican bust.

It is, of course, impossible to brush away the cynical conclusion that crushing workers and their economic power was and remains a feature of the capitalist system and its stewards in government and finance. Reagan and his merciless smashing of the air traffic controllers union—leading to years of union-busting—coincided neatly with those 30+ years of non-existent raises, as well as private-sector union membership falling off a cliff. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, there were between 200 and 400 major strikes by labor unions each year. When Reagan left office in 1988, there were 40. There were just seven in 2017.

Unsurprisingly, taking away power from workers and giving it to bosses made things worse for workers. The Reagan years radically widened the income gap between low- and high-income earners for the following three decades—even though the average American worker was increasingly efficient and productive year after year. Between 1979 and 2019, productivity increased 60% while wages only went up 16%. Windfall profits went to shareholders and owners.

Ironically, wage stagnation came to its merciful, all-too-brief conclusion in 2020, when people weren’t working at all. Between March and June of that year, when many furloughed workers were sitting at home during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, government stimulus checks caused real wages to increase relative to inflation. Increased savings allowed employees to quit in droves in the so-called Great Resignation; labor unions chalked up some impressive victories as emboldened wage slaves stood up for themselves.

The worst inflation crisis of the past century was sparked by the end of World War II-era price controls on a wide array of rationed commodities and a surge in pent-up demand. (The latter is, at a smaller scale, the main force behind inflation today.) In 1947, the inflation rate rose to 20%. What’s interesting is what the Fed did not do in response: raise interest rates. It couldn’t. It didn’t have that power then.

Instead, fiscal policy makers refused to extend additional credit to the big banks — which had contributed to inflation — and waited for consumers to satisfy their pent-up demand. This they did by 1948. With no one to slam on the brakes, there was a quick, mild recession in 1949 followed by an impressive period of economic expansion in the 1950s. This episode from the Truman era strongly suggests that current Fed policy of raising short-term interest rates is a mistake. The only solution to pent-up demand is no solution at all. Just sit back and wait.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

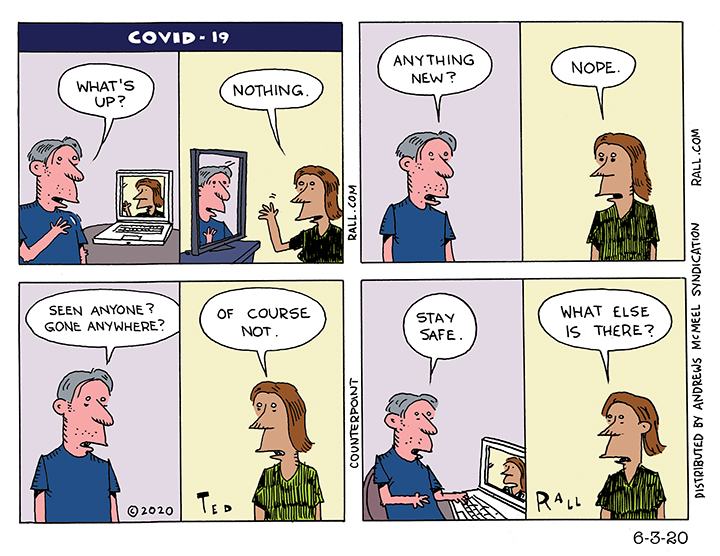

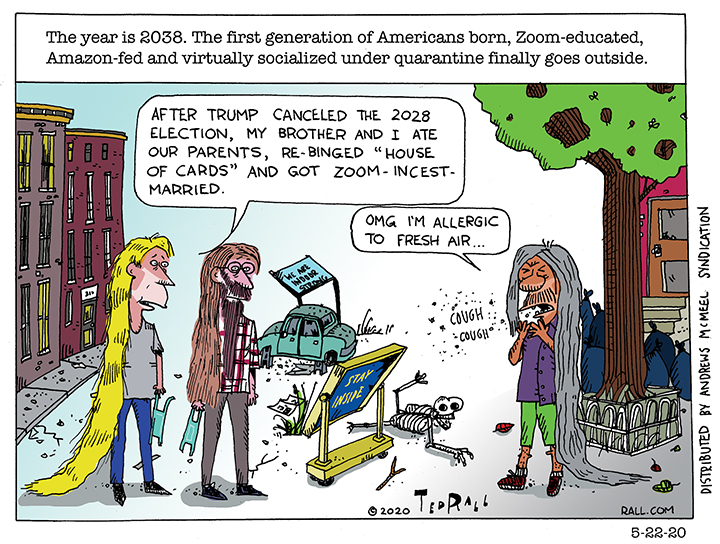

Our First Lockdown Experiment Failed. Let’s Not Try a Second One.

Shutting down businesses and schools felt to many people like a natural response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But the extended coronavirus lockdown of 2020 did not follow any widely-accepted standard strategy; lockdowns were sporadic and short-lived during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the most recent historical parallel. Encouraging and coercing tens of millions of people to shelter in place in 2020 was one of the most radical social engineering experiments in modern history, as novel as the coronavirus itself.

Shutting down businesses and schools felt to many people like a natural response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But the extended coronavirus lockdown of 2020 did not follow any widely-accepted standard strategy; lockdowns were sporadic and short-lived during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the most recent historical parallel. Encouraging and coercing tens of millions of people to shelter in place in 2020 was one of the most radical social engineering experiments in modern history, as novel as the coronavirus itself.

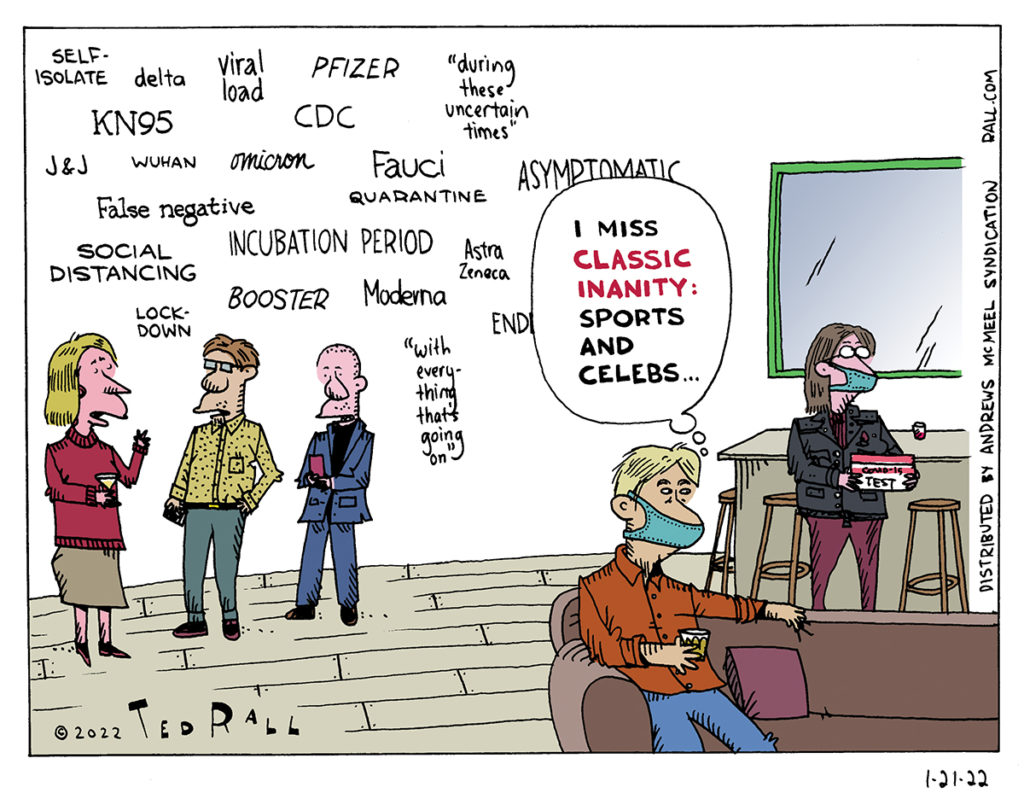

The political impulse to cancel events and close nonessential services we experienced during the spring and summer of 2020 is reemerging as the highly contagious, albeit anecdotally less severe, omicron variant sweeps through New York City and other hotspots. Broadway theaters, rock and hip-hop performers have canceled performances, the Rockettes closed their season a week early and Mayor Bill de Blasio is considering curtailing attendance at the city’s annual ball drop at Times Square. Rumors that New York City is considering another public-school system lockdown are sparking panic among parents.

Harvard has moved back to remote learning. The World Economic Forum in Davos has been canceled. Quebec is under lockdown, joining the Netherlands. The United Kingdom is considering one.

So, clearly, is the Biden Administration. The feds can’t order lockdowns. But they can pressure states and cities to enact them.

White House chief medical adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci says he doesn’t “foresee” another national lockdown in the United States—yet. Students of political messaging will take note of the careful if-then conditional sentence structure in Fauci’s statement on ABC’s “This Week”: “I don’t see that in the future if we do the things that we’re talking about,” Fauci said. “The thing that continues to be very troublesome to me and my public health colleagues is the fact that we still have 50 million people in the country who are eligible to be vaccinated who are not vaccinated.” What are the odds that vaccine resisters will change their minds in the next week or two?

Americans should consider, as we stare down the barrel of a second wave of “slow the spread”-motivated societal freezes, the pros and cons of the first one last year. Spoiler alert: this is not a movie that deserves a sequel.

Co-conceived in 2005 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Homeland Security and the World Health Organization, the Pandemic Influenza Plan developed to “prevent, control, and respond to…novel influenza A viruses of animal (e.g. from birds or pigs) with pandemic potential,” according to the Centers for Disease Control, was the blueprint for the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza deployed by the Trump and Biden administrations 15 years later to coordinate “all levels of government on the range of options for infection-control and containment, including those circumstances where social distancing measures, limitations on gatherings, or quarantine authority may be an appropriate public health intervention.” Federal officials turned to this Bush-era guidebook when COVID-19 came to America.

It pains this leftist to admit it, but conservatives who warned of the economic and psychological costs of the 2020 lockdown turned out to have been correct. “Lockdowns do not prevent infection in the future. They just don’t. It comes back many times, it comes back,” President Donald Trump said in April 2020, shortly before much of the country succumbed to lockdown fever. He looks prescient.

With the delta and omicron variants still raging, cost-benefit analysis of the COVID lockdown requires hard data that won’t be available for years. But one thing is clear: the lockdown experiment was far short of an unqualified success.

The economic cost has been staggering. “COVID-19–related job losses wiped out 113 straight months of job growth, with total nonfarm employment falling by 20.5 million jobs in April [2020],” according to a study by the Brookings Institute. 200,000 businesses more than average failed. Harvard economists David Cutler and Lawrence Summers have estimated the total cost of the crisis, much of which is attributable to the lockdown, at $16 trillion if the pandemic were to end this fall—i.e., now.

2020-21 was the Great Lost Year of American public education. With Black students five months behind where they would have been otherwise and whites two months back, virtual instruction was virtually educational.

But what about the benefit? Some studies claimed that lockdowns prevented nearly 5 million cases in the United States; at a mortality rate of 1.6% that works out to 80,000 fewer coronavirus fatalities thanks to the lockdown. But analyses of “excess deaths” indicate that at least 300,000 Americans more than usual died last year due to causes other than the virus itself. Increased alcohol consumption, reduced physical activity and depression culminating in suicide (not last year, when fewer people killed themselves, but in future years) will claim lives years into the future. If the lives-saved column of the ledger comes out a net positive, it probably won’t be by much.

As for ordinary Americans, we are voting with our feet: 72% of respondents to a December 14th Ipsos poll said they plan to see family or friends outside of their household over the holidays.

This country can’t handle more lockdowns.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of a new graphic novel about a journalist gone bad, “The Stringer.” Order one today. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

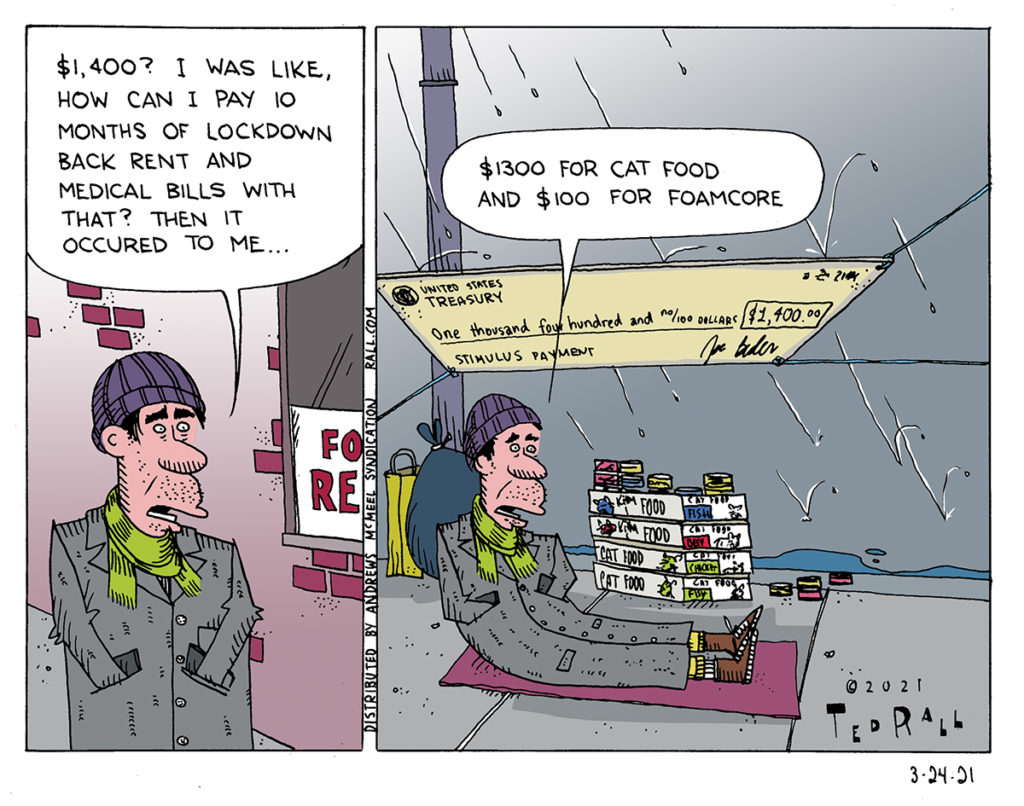

How You Can Survive on $1400

A $1.9 trillion stimulus bill sounds like a lot of money, and it is, but a single payment of $1400 isn’t going to go very far for the 40 million people who lost their jobs over the last year and the millions of people who are facing eviction or foreclosure. Maybe all they need to survive is a little imagination.

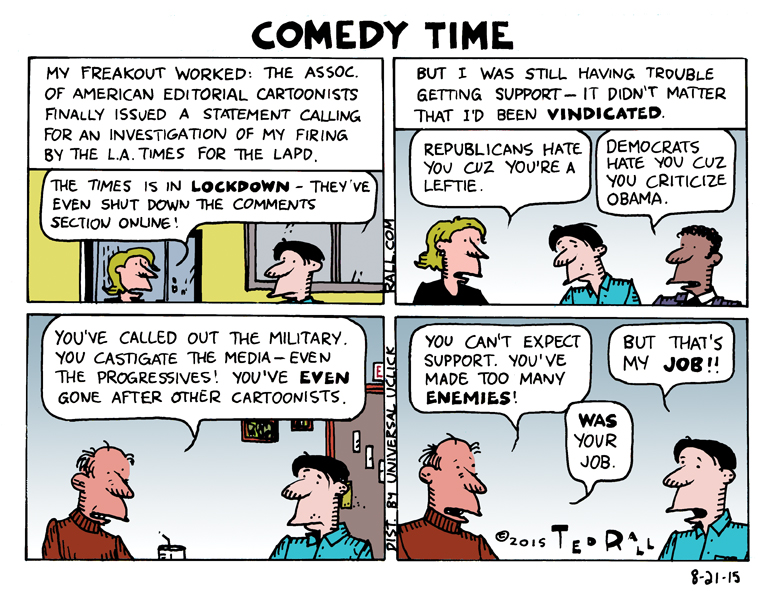

Comedy Time

Even after the Assocation of American Editorial Cartoonists issued a formal statement calling for an investigation of the LA Times’ firing of me as a favor to the LAPD because I criticized police brutality, I found it difficult to get support from, well, everybody. Because one of the defining aspects of satire is that, eventually, you end up making fun of everyone. Who end up hating you.