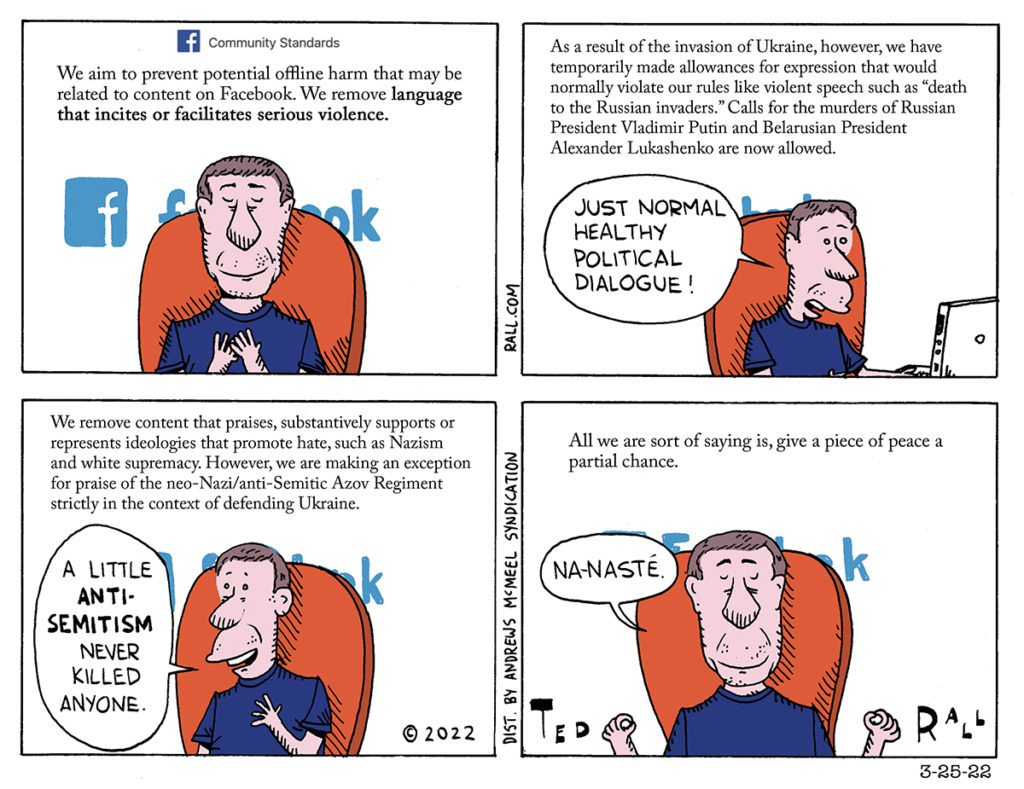

The parent company of Facebook and Instagram constantly brags that it does everything that it can in order to reduce violent speech on its platforms. However, it makes exceptions for political hate speech that they happen to agree with. Can you really call them standards if you have exceptions to them?

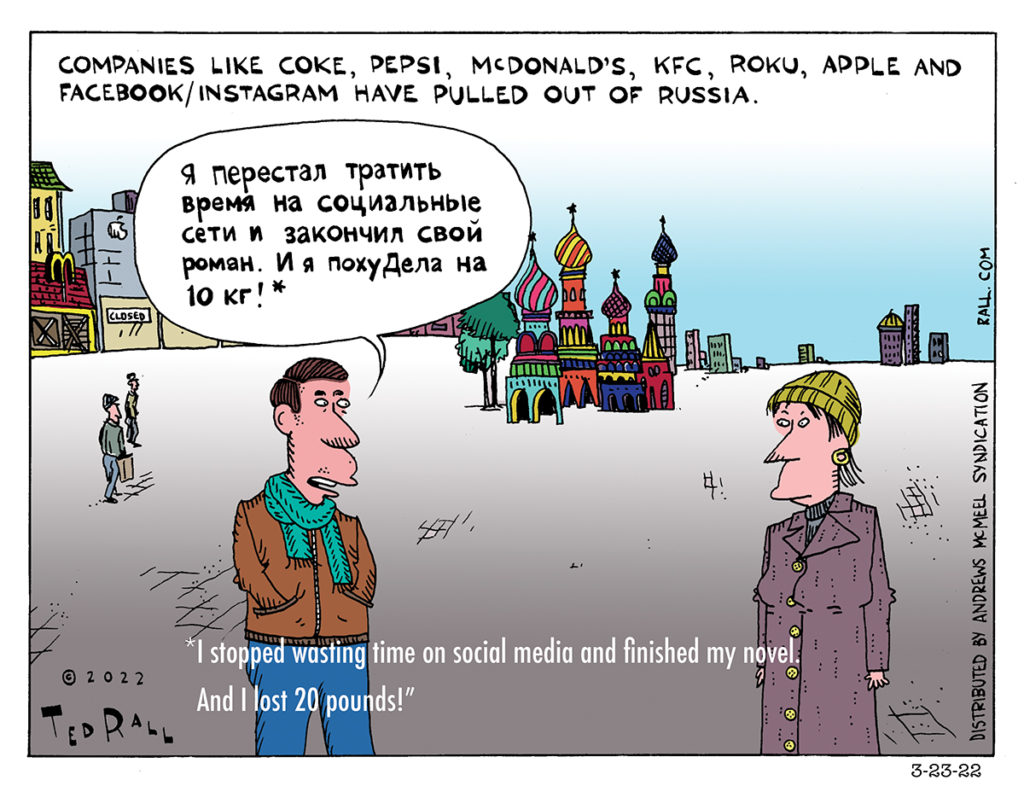

Some Sanctions against Russia Are a Blessing in Disguise

Companies that produce disgusting crap like Coke, Pepsi, McDonald’s, KFC, etc., are boycotting Russia and shutting down operations there. This will no doubt improve the health of the average Russian. At the same time, disgusting tech companies like Facebook and Apple are pulling out as well, freeing the Russian people from the shackles of stupid social media and other toxic forms of communication.

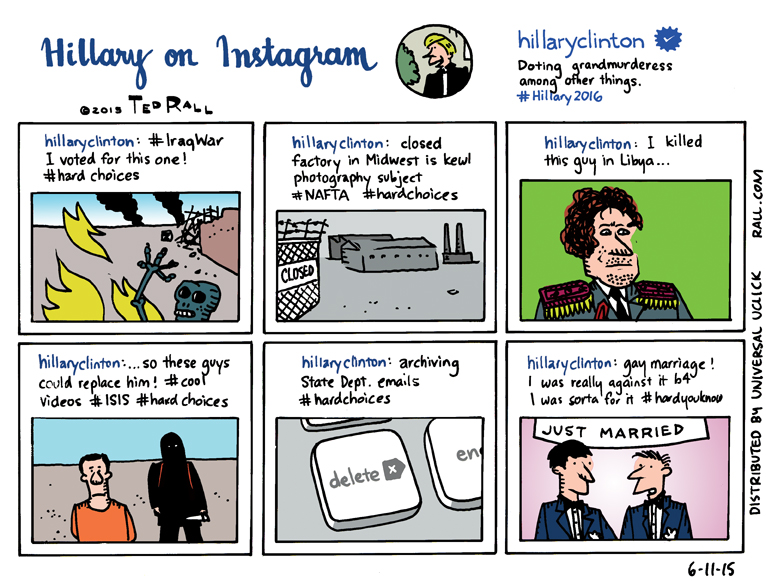

Hillary on Instagram

The Hillary Rodham Clinton campaign is now on Instagram, with a light joke about “Hard Choices”: a reference to a photo of her pantsuits in red, white and blue. It’s part of the effort to make a politician with blood-soaked hands look like just another ordinary American grandmother…and it just might work.

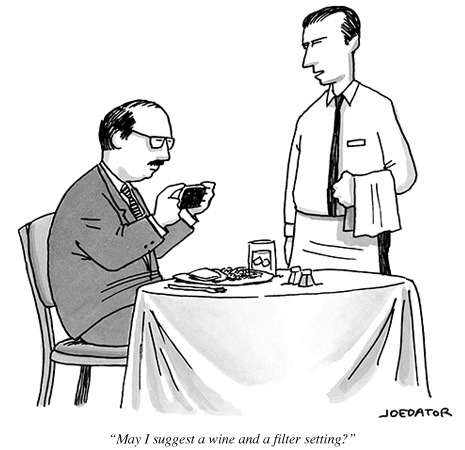

SYNDICATED COLUMN: The New Yorker is Bad for Cartooning

When you tell people you’re a cartoonist, one of the first things they ask you is whether you’ve ever had a cartoon published in The New Yorker. I don’t blame them. Everyone “knows” that running in the same pages that showcase(d) Addams and Chast proves you’re one of the best.

The marketing hype behind New Yorker cartoonist and cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s new memoir — featuring something I really am jealous about, a “60 Minutes” interview — further cements the magazine’s reputation as cartooning’s Olympus.

“For nearly 90 years, the place to go for sophisticated, often cutting-edge humor has been The New Yorker magazine,” says Morley Safer.

As is often the case, what everyone knows is not true.

Here’s a challenge I frequently give to New Yorker cartoon proponents. Choose any issue. Read through the cartoons. How many are really good? You’ll be surprised at how few you find. But don’t feel bad. Like the idea that the U.S. is a force for good in the world, and the assumption that SNL was ever funny, the “New Yorker cartoons are sophisticated and smart” meme has been around so long that no one questions it.

From the psychiatrist’s couch to the sexless couple’s living room to the junior executive’s summons of his secretary via intercom, New Yorker cartoons are consistently bland, militantly middlebrow, and mind-numbingly repetitive decade after decade.

Which is fine.

What is not fine is not seeing fluff for the crap that it is.

The New Yorker is terrible for cartooning because it prints a lot of awful cartoons, and uses its reputation in order to elevate terrible work as the profession’s platinum standard.

They pay pretty well. Which prompts too many talented artists, who under a better economic and media model would produce interesting, intelligent, great cartoons (and did so, in the alternative weekly newspapers of the 1990s, for example), to pull their satiric punches and stifle their creativity. Of course, not every cartoonist follows the siren call to Mankoff’s office in the Condé Nast building. It is possible to make a living selling cartoons to other venues. I do. Still, the New Yorker casts a long shadow, silently asking a question one fears is heard by art directors everywhere: If you’re so smart and so funny and so talented, why aren’t you in The New Yorker?

Mankoff and his predecessors have created a bizarro meritocracy in reverse: bad is not merely good-enough, but the crème-de-la-crème. It’s like singling out the slowest runners in a race and awarding them prizes and endorsements. Some runners, devoted to excellence and the love of competition, will keep running as fast as they can. But fans will wonder why they don’t wise up.

What makes a cartoon good/funny? Originality, relevance, insight, audacity and random weirdness. (There are other factors, which I’ll remember after a minute after it’s too late.)

Originality in both substance and form, and in both writing and drawing, is the most important component of a great cartoon. It is rare to find. Cartooning is a highly incestuous art form; most practitioners slavishly copy or synthesize the work of their forebears. Editors and award committees (composed of editors) have short memories and no historical knowledge, which feeds lazy cartoonists’ temptation to present initially brilliant, but now hackneyed and recycled, ideas as their own. Other cartoonists’ punch lines, structural constructions, even their drawing styles, are routinely stolen wholesale; alas, media gatekeepers never have a clue. All too often, the plagiarists collect plaudits while the victims of their grand larceny of intellectual property die sad and alone.

Well, maybe not sad or alone. But annoyed over beer.

Give The New Yorker its due: since it reacts to trends and news in politics and culture, the magazine’s funniest cartoons can be relevant. Sadly, their single-panel gags say less than Jerry Seinfeld’s jokes about nothing. At best, name-checking Lady Gaga or hat-tipping Instagram elicits a knowing ha ha, they read the same stuff I do (i.e. The New York Times).

Mankoff’s book takes its title from the line of perhaps his greatest hit: “How about never — is never good for you?” This is an “nth degree” concept. What happens if the back-and-forth busy people often experience when they’re trying to set a rendezvous achieves its ultimate, most extreme conclusion? It also showcases anxiety and insecurity among the aspirational bourgeoisie, the not-so-secret sauce of New Yorker humor, for nearly a century. But what does Mankoff’s cartoon say? What does it mean?

A cartoon doesn’t have to be political to matter. “The Far Side” wasn’t political, but most of Larsen’s work reveals something about human nature to which we hadn’t previously given much thought. To be funny, a cartoon must rise above it’s-funny-cuz-it’s-true tautology. Mankoff’s “never” toon does not. Nor does the magazine’s famous “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” piece, drawn by Peter Steiner in 1993 (though Matt Petronzio’s post-Snowden update does).

If you can credibly reply “so what?” to a cartoon, odds are it’s not worth your time.

A great cartoon is funny because it’s dangerous.

A 19th century relic of the degrading “shape ups” depicted in the film “The Bicycle Thief,” The New Yorker‘s submission policy is a system — intentional or not, no one knows — that filters out originality and rewards a schlocky “throw a lot of shit at the wall and see if anything sticks” approach to cartooning. Every Wednesday morning, Mankoff holds court, looking over submissions of cartoonists who must present themselves in person rather than, say, email or fax their work. Because submissions must be fully drawn and the odds of acceptance increase with the number of cartoons presented, New Yorker artists deploy dashed-off, sketchy drawing styles that haven’t changed much since the 1930s.

Editors at other publications work with professional cartoonists they trust to consistently deliver high-quality cartoons, and help them hone one or two rough sketches to a bright sheen. The results are almost always better than anything that runs in The New Yorker — yet “60 Minutes” doesn’t notice.

“How much do the cartoonists make? Editor [David] Remnick will only say: nobody’s becoming a millionaire,” Safer says in the “60 Minutes” piece.

Well, Mankoff did. But that’s another story for another time.

(Support independent journalism and political commentary. Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

SYNDICATED COLUMN: Good Reasons to Hate Big Tech

We love computers and other electronics, but — not unlike an addict’s opinion of his dealer — we hate the companies that sell them to us. Now our contempt for Silicon Valley is expanding to include tech workers.

In San Francisco, where locals know the techies best, 30-year-old worker bees are taking as much heat as their billionaire CEO overlords.

Geographical familiarity breeds political contempt.

Just as Zuccotti Park gave birth to Occupy Wall Street’s clarion cry against the predator class henceforth to be known as the Banksters, San Francisco bus stops have become ground zero in a backlash against Big Tech. Oversized SUV-like buses that ferry Google staffers down the Peninsula provoke anger by clogging public transit stops in a city whose crumbling fleet of city vehicles is starved of funding. Private tech company buses have been blocked by protesters who object to gentrification fueled by the soaring rents paid by deep-pocked tech workers. A bus window got smashed. Across the bay in Berkeley, demonstrators even showed up at the home of a Google engineer to hold him to account for his dual role as tech dystopian (he runs Google’s creepy robot car project) and real estate developer.

Save for a window and a few Google worker tardy notices, nothing has been harmed. Days of Rage this ain’t.

Despite the relative mellowness of it all, any hint that American leftism is livelier than a withered corpse prompts establishmentarians into anxious fits that the streets will soon run red with the blood of fattened-on-organic-veal-and-green-smoothies technorati. In Salon, the usually steady Andrew Leonard lectured San Francisco’s dispossessed that street actions like slashing bus tires are “bullshit,” opining that “delivering passionate rhetoric at a public hearing on city policy toward private shuttles is part and parcel of how a democratic society operates.” (Or doesn’t operate, by his very own account.)

“This is a very dangerous drift in our American thinking,” Tom Perkins, an 82-year-old venture capitalist who helped fund the initial launch of Google, wrote in an instantly infamous letter to the The Wall Street Journal, comparing dislike of 1%ers to Nazi attacks on Jews. “Kristallnacht was unthinkable in 1930; is its descendant ‘progressive’ radicalism unthinkable now?” (Note to Perkins: You’re old enough to remember that Nazism was a right-wing movement.)

“With spokesmen like Mr. Perkins,” David Streitfeld responded in The New York Times, “the tech community will alienate the entire country in no time.”

Gallup’s 2011 poll of public perceptions found that Americans view the tech sector more positively than any other industry but that, I think, is not going to last. Because there are lots of good reasons to hate Big Tech.

The root of our contempt for the tech biz is that all our economic eggs are in their basket. Manufacturing is never coming back. Whatever chance the U.S. economy has of recovering from the 2008-09 collapse (and, for that matter, the 2000-01 and 1989-93 recessions) lies with the tech sector. But the technies don’t care. And they’re barely employing anyone.

Facebook has 6,300 employees, Twitter has 2000, Instagram has 13.

The Big Three auto companies each employ between 2.5 million and 3 million workers directly or through subsidiaries and contractors.

It’s not like Facebook couldn’t use more American workers. Because Mark Zuckerberg can never grab enough loot for himself, Facebook does without the basics, like customer service reps. They don’t even have a phone number.

It’s hard to feel warm and fuzzy about companies that don’t hire us, our neighbors or, well, anyone at all.

Or answer the phone.

Fair or not, we feel vested in tech. The average American spends thousands of dollars a year on electronics and tech-related services, including broadband Internet. Objectively, we spend more on housing, food and energy — but those expenditures feel impersonal. Unlike our devices, we’re not constantly reminded of them.

Smartphones, tablets and desktop computers are central to our minute-by-minute lives, serving as a constant reminder of our material support to the digerati.

Every time we pick up our iPhone, we recall the $400 we spent on it. (And the $300 on its once cool, now lame, two-year-old precursor.) This makes us think of historic, extravagant profits pocketed by their makers. We can’t help but remember the over-the-top paychecks collected by their makers’ CEOs, including the incompetent ones. Also popping to the front of our consciousness is the despicable outsourcing of manufacturing to slave labor contracting firms like Foxconn, where abused Chinese workers attempt suicide so often that the company had to install netting around dormitory windows. Charmingly, Foxconn began requiring new hires to sign an agreement releasing the company from liability if they kill themselves.

Few industries gouge consumers as ferociously as wildly profitable tech outfits like Microsoft, Adobe and Apple.

Not only have Americans been reamed by Big Tech — they know they’ve been reamed. Which sets the stage for big-time resentment.

In the past, wealthy companies and individuals mitigated populist resentment by paying homage to the social contract — i.e., by giving back. Henry Ford paid assembly line workers more than market rates because he wanted them to be able to afford his cars. 19th century robber barons like J.P. Morgan and Cornelius Vanderbilt built museums and contributed to colleges and civic organizations. These gestures helped keep socialism at bay.

Whether it’s due to the influence of technolibertarianism, pure greed or obliviousness, tech titans are relative skinflints compared to the manufacturing giants they’ve supplanted. Yes, there’s the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (though its “philanthrocapitalism” model is staggeringly ineffective). But Steve Jobs kept almost every cent. Facebook and Twitter are basically “non-players” in the philanthropy world. Google doles out roughly 0.02% of its annual profits in charitable grants.

Some say the techies aren’t cheap — just skittish. “A lot of the wealthy in Silicon Valley are newly wealthy,” said E. Chris Wilder, executive director of the Valley Medical Center Foundation in San Jose. “That money still feels a little too tenuous; still feels fleeting. And the economic downturn has reinforced that feeling.”

Whatever the cause, underemployed and overcharged Americans expect tech’s 1% to start stepping up.

(Support independent journalism and political commentary. Subscribe to Ted Rall at Beacon.)

COPYRIGHT 2014 TED RALL, DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM