When you’re trying to get people to change forms of address, you have two options. You can bully them. Or you can convince them.

Coercion can do the job, provided you possess that power. Less than 10 years after the Bolshevik revolution, Soviet citizens were mimicking the practice of pre-revolutionary communists, who called one another “comrade.” That anti-honorific honorific, meant to reinforce the regime’s message that all citizens were equal, vanished along with the collapse of the USSR and its replacement by a capitalist system that claimed nothing of the sort.

Conversely, convincing can be easy—when the proposed modification simplifies language. Introduced in the late 1960s and popularized by the 1972 launch of Gloria Steinem’s magazine of the same name, “Ms.” eliminated the guesswork inherent in the Miss/Mrs. binary, which required knowledge of a woman’s marital status and reinforced patriarchy by defining females by their relationship with men. Here, political progress hitched a ride on practicality.

Solving the is-she-or-isn’t-she problem led to rapid widespread acceptance. The GAO approved the use of Ms. on official government documents a mere month after the magazine appeared. By 2009 the European Parliament had officially banned the titles of Miss, Mrs., Madame, Mademoiselle, Frau, Fraulein, Senora and Senorita. The American Heritage Book of English Usage states: “Using Ms. obviates the need for the guesswork involved in figuring out whether to address someone as Mrs. or Miss: you can’t go wrong with Ms. Whether the woman you are addressing is married or unmarried, has changed her name or not, Ms. is always correct.”

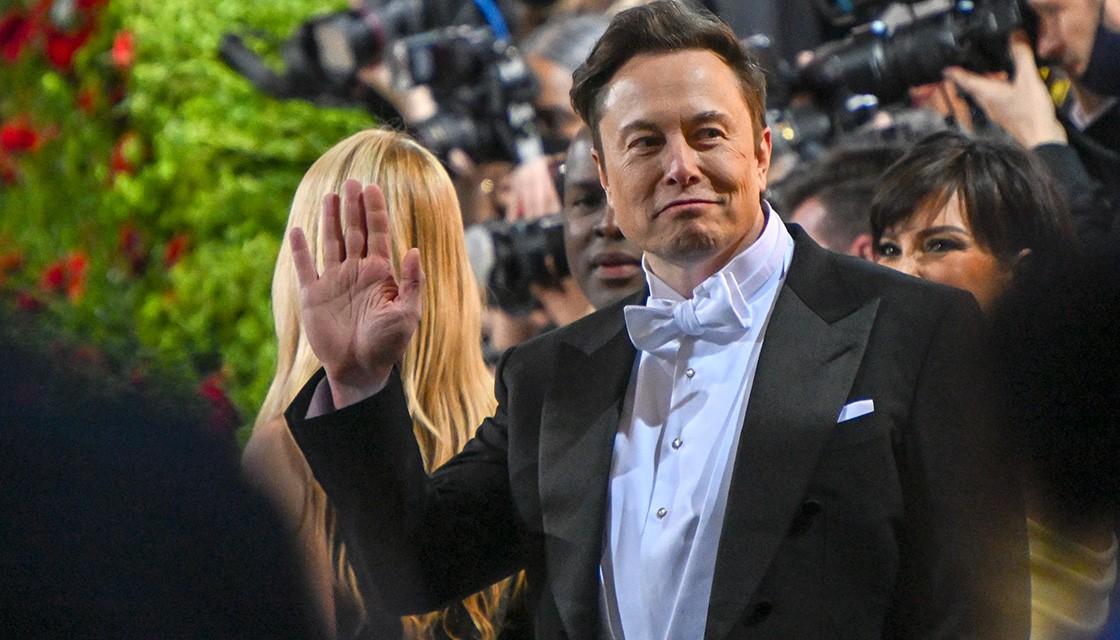

As is his gloriously insensitive wont, Elon Musk recently wandered into the politics of a proposed linguistic change that is not going nearly as well: transgender activists’ project of using titles and pronouns to reinforce the message that gender (as opposed to sex) is inherently arbitrary, exists on a broad spectrum and non-binary. “My pronouns are Prosecute/Fauci,” Musk tweeted. But I’m not interested in the Fauci thing.

Astronaut Scott Kelly complained: “Elon, please don’t mock and promote hate toward already marginalized and at-risk-of-violence members of the #LGBTQ+ community.”

“I strongly disagree,” Musk replied. “Forcing your pronouns upon others when they didn’t ask, and implicitly ostracizing those who don’t, is neither good nor kind to anyone.”

Musk is a lout. He’s also mistaken. No one is forcing anyone to do anything. LGBTQ+ folks are asking. When someone asks you to call you by a certain name or in a certain way, the polite thing to do is to comply. My legal first name is Frederick. My first-grade classmates insisted on addressing me by the diminutive Fred, which was annoying due to the popularity of “The Flintstones” TV show at the time. I went by Ted, from my middle name Theodore, beginning in second grade. Yet even now some people—jerks on a power trip—want to call me Fred or Freddy.

Whether it’s an individual or a class of people or a nation—the U.S. government childishly continues to use the old British colonialist name Burma rather than Myanmar, which it has been since 1989—I say call people what they want to be called.

The challenge for activists advocating for the 1.6% of Americans who self-identify as transgender or nonbinary is that the change they are asking for increases rather than decreases the linguistic complexity of concepts they think and talk about all the time. The remaining 98.4% are no longer male or female but cis male or cis female—a tortured prefix that neither rolls off the tongue nor has roots in anything familiar to most English speakers. Unlike Ms., cis-ification creates a problem rather than solves one.

Pronouns and forms of address are among the most basic building blocks of everyday speech. He/him and she/her are simple. Trans-friendly grammar is confusing.

Along with novel pronouns like they/them, favored by transgender people, are others like ze/zie, xe/xem and ve/ver. Americans are being introduced to gender descriptors that only recently began to enjoy distribution in mainstream media: genderqueer, pangender, genderfluid, neutrois, two-spirit, intersex. New York City officially recognizes 31 distinct gender identities, yet Americans do not know anyone who is transgender, do not see transgender people or issues on the news they consume and do not know what many of these terms mean.

On the other hand, most respondents to polls say they would support their child if they were to identify themselves as transgender and would use whatever pronouns they preferred. The challenge isn’t transphobia. It’s convincing people to modify their behavior and speech in response to changes that aren’t yet visible enough to feel real to many people.

Elon Musk tapped into a silent but widespread feeling, even among people who may be transgender allies, that pronoun wars are silly.

“We cannot assume someone’s pronouns, in the same way we cannot assume someone’s name,” a statement by the Trevor Project declares. “It’s always best to confirm with a person what their name and pronouns are. You can do that by asking, or by introducing your own pronouns when you meet a person, which gives them the opportunity to share theirs.” Who, outside rarified political or academic gatherings, actually does this? In the real world, people assume others’ gender based on their appearance—and they’re almost always correct. Politics fail when activists promote fantasy: even among Democrats, only 16% agree that everyone should generally say their pronouns.

I may not be the most butch dude in the world but, even so, no one has ever needed to be told that my pronouns are he/him. After six decades on the planet, why has this (until recently) non-issue become so fraught that I’m scared to be writing this essay lest I get pilloried on Musk’s Twitter? Kamala Harris recently welcomed a group of disability advocates with hilariously trite obviousness: “I am Kamala Harris. My pronouns are ‘she’ and ‘her.’ I am a woman sitting at the table wearing a blue suit.” Well, duh. Has anyone ever wondered about the veep’s pronouns?

The pronoun thing also feels irrelevant to people who live in communities where they not only don’t know anyone who is transgender or nonbinary, no one they know knows someone who is. Politics fail when they don’t connect to perceived reality.

Can transgender Americans achieve full equality and eliminate discrimination without a radical grammatical transformation? If not, there is only one way to get there absent the kind of wholesale cultural transformation that took place in revolutionary Russia and its attendant social pressures. Stop preaching and wage a patient, persistent educational campaign that convinces most citizens that a more complicated world is a better one.

I’m not optimistic.

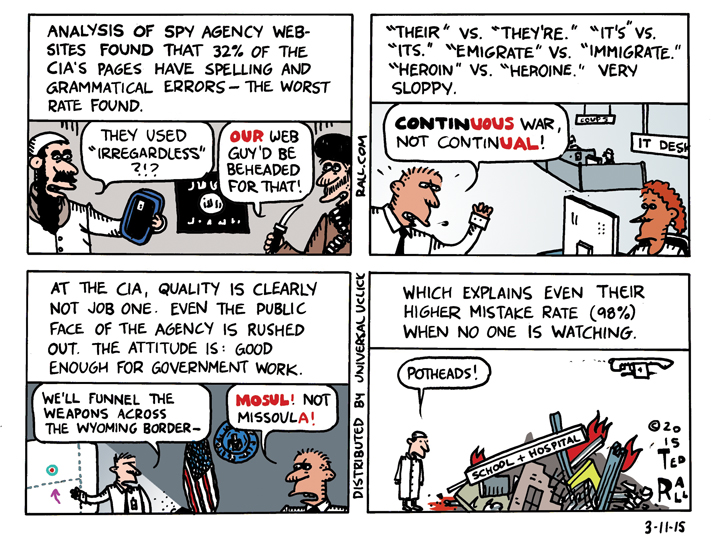

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, co-hosts the left-vs-right DMZ America podcast with fellow cartoonist Scott Stantis. You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)