Puritanism’s obsession with guilt and shame, Nathaniel Hawthorne believed, was America’s original sin. We haven’t made much progress since “The Scarlet Letter.”

Do the crime do the time, goes the cliché. In the United States, when the time ends the shaming begins.

It starts when you look for a job. At least 65 million Americans have a felony or misdemeanor criminal record that makes them ineligible to work for the more than 90% of companies who run background checks to weed out applicants with a record. As for the few ex-cons who slip through this electronic dragnet, they are required by shaming laws to tell prospective employers about their checkered past. (Some states have slightly liberalized the requirement with laws like New York’s “Ban the Box” law, which requires disclosure only at the job offer stage.)

The only social benefit to convict-shaming is the shaming itself. “The irony is that employers’ attempts to safeguard the workplace are not only barring many people who pose little to no risk, but they also are compromising public safety. As studies have shown, providing individuals the opportunity for stable employment actually lowers crime recidivism rates and thus increases public safety,” notes a 2011 report by the National Employment Law Project. But capitalism is dog-eat-dog. Each company looks out for itself, society be damned.

I dug into the issue of convict-shaming after an op-ed I wrote for the Wall Street Journal calling for automatic expungement of records of people previously convicted of buying recreational marijuana in amounts that would now be legal prompted a discussion online. Some readers agreed with me that it’s absurd to keep punishing people for acts that are now legal. Others felt that if it was a crime at the time a criminal is still a criminal.

In most countries most employers do not conduct criminal background checks and there is no legal or ethical expectation that ex-cons reveal that they have committed a crime.

A person is convicted, sentenced to prison time and/or to pay a fine, serves the term and coughs up the money. Isn’t there a logical contradiction between release—which assumes an inmate no longer presents a danger to society—and public shaming? I am thinking of one of the most extreme examples of convict-shaming, Megan’s Law. Based on the false assumption that sex offenders have a high rate of recidivism, these statutes require that released inmates register in a database and notify local police and their neighbors of their address.

“What we’ve done,” Radley Balko wrote in The Washington Post in 2017, “is allowed sex offenders to be ‘released’ from prison, but then made it impossible for them to live anything resembling normal lives.” Websites linked to Google Maps allow anyone to check if their neighbor is a convicted sex offender. In some jurisdictions sex offenders are not allowed to reside within a set distance of a school or public park. In 2017 President Obama signed an “international Megan’s Law” that requires sex offenders against children to have the sentence “The bearer was convicted of a sex offense against a minor” stamped into their U.S. passports. So much for business travel.

Why such laws are popular is obvious. If a child molester lives down the block, parents want to know.

But vigilantes have used public Megan’s Law registries to locate and murder released sex offenders. In some communities the school and park restrictions are so draconian that there are so few legal places for released sex offenders to live that they’re forced to become homeless in order to comply with the law. All that harassment serves no real purpose except—you guessed it—serving the desire for cheap vengeance. “The [Megan’s Law] registry really didn’t protect kids at all” because “most child sexual abuse takes place in the home” and most of the victims of sex offenders listed in Megan’s Law databases are adults, says criminologist Emily Horowitz, author of Protecting Our Kids?: How Sex Offender Laws Are Failing Us.

To look at it another way: if sex offenders are dangerous, shouldn’t we keep them locked up rather than rely on mere shaming? Megan’s Law can’t stop a child molester from raping a child.

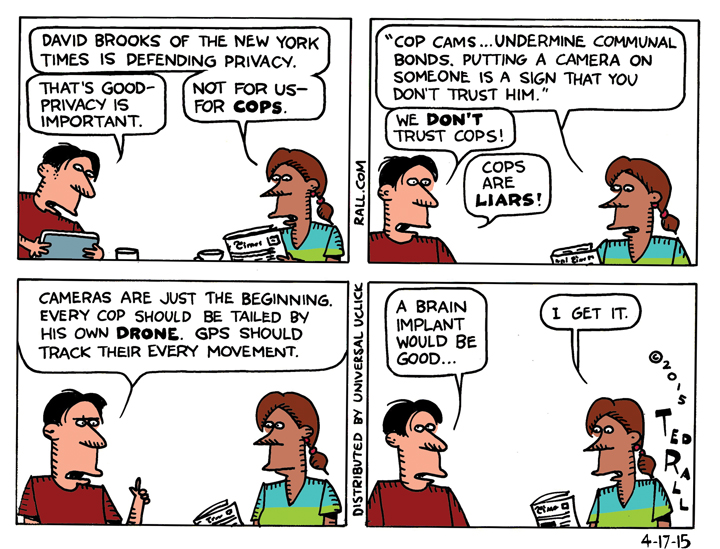

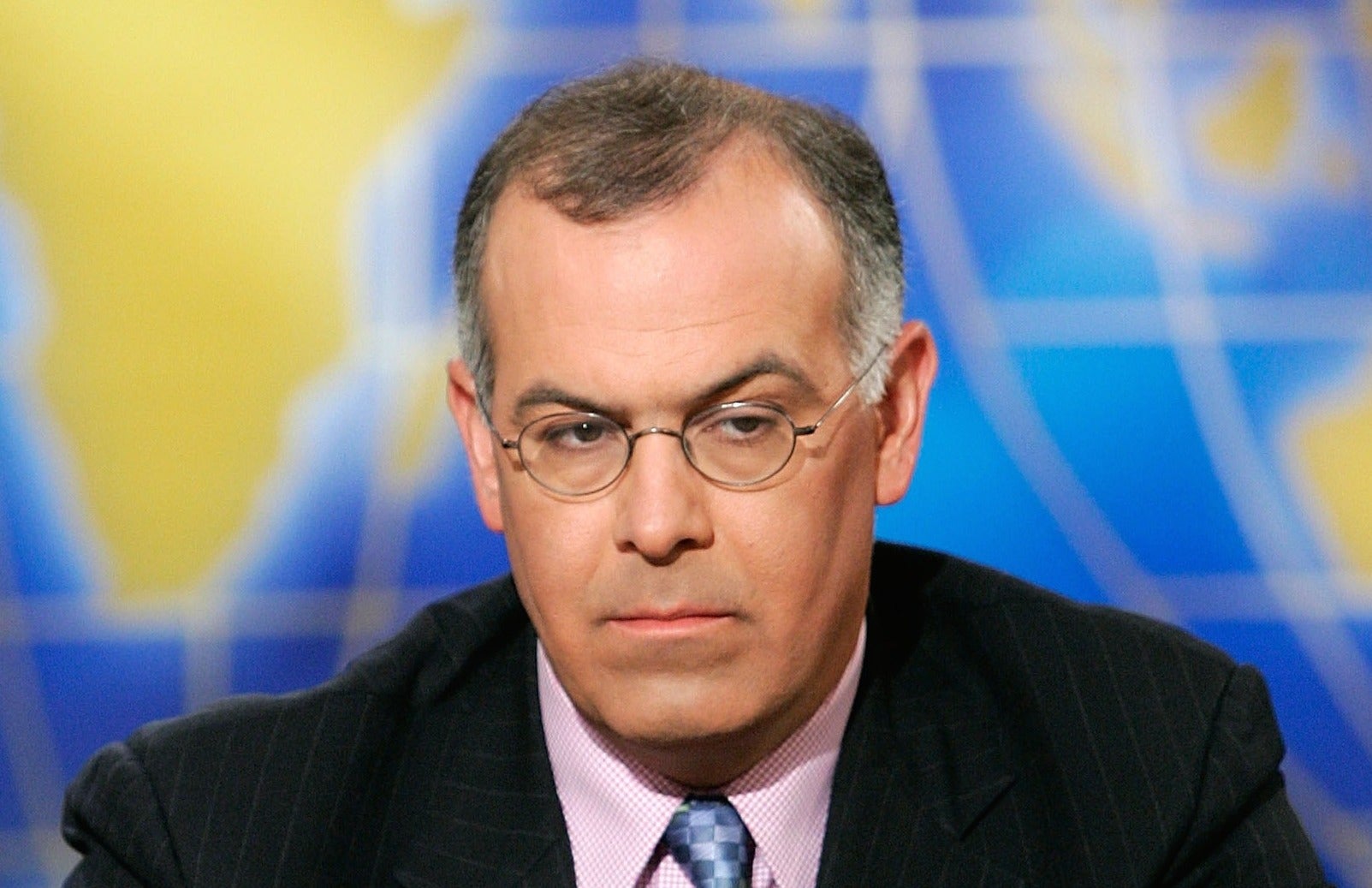

David Brooks of The New York Times has the latest MSM take on what he calls the “Call-Out Culture,” in which self-appointed guardians of identity politics (critics call them “social justice warriors”) swarm those accused of political incorrectness on social media feeds in order to shame, ostracize and demoralize them. “I don’t care if she’s dead, alive, whatever,” a man who went after a young women (ironically in retaliation for cyberbullying) told NPR.

Chinese Internet users have elevated doxxing and social media shaming to a high art called the “human flesh search engine” that costs victims their friends, family associations, jobs and sometimes their lives. But China is an outlier. While the phenomenon exists everywhere anecdotal evidence suggests that online “call-out culture” is neither as sophisticated or widespread in most nations as it is here in the United States.

It’s impossible to discuss shame culture without talking about the #MeToo movement. Criminal prosecution of accused sexual predators like Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey are exceptions. For the most part #MeToo is a shame-based movement. Sometimes, as in the case of comedian Aziz Ansari’s bad date, shame seems excessive and misplaced. In many cases, the targets seem to have had something coming—since it’s not jail we settle for job loss—and it’s unlikely they would have faced consequences otherwise. Then there are those who-the-hell-knows cases like Louis C.K. where the behavior was weird and pervy and consent is a nebulous issue (he asked, the women involved “laughed it off”).

#MeToo has a mixed record. I can’t help wonder if, for all the shattered careers and former celebrities who now take their meals at home rather than eating out at a fancy restaurant, the victims feel cheated. On the one hand, something finally happened to their tormentors. On the other, shame fades. Trauma is often forever.

Evildoers deserve real punishment. After punishment has been doled out shame is both a poor substitute and counterproductive overkill. But it’s what we’ve got.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)

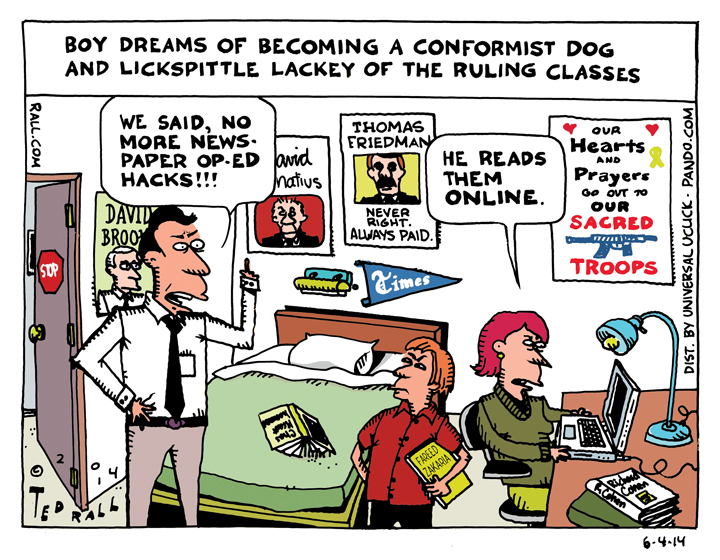

If you suck at your job, you’ll get fired.

If you suck at your job, you’ll get fired. Stipulated: David Brooks isn’t that smart.

Stipulated: David Brooks isn’t that smart.