“I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters, okay?” Donald Trump said at an Iowa campaign rally in January of 2016. That remark gets quoted, mostly by liberals bemoaning the unquestioning loyalty of the president’s stupid supporters, a lot.

But there’s another, more interesting, facet of that meme: Trump, it’s clear, can get away with just about anything—impeachment included. He will be impeached without turning a single voter against him.

Nothing has ever been less deniable than the president’s imperviousness to, well, everything. Trump’s haters hate it, his fans love it, everyone accepts it. A month ago Trump’s lawyers for real argued in open court that, if their client actually were to go on a shooting spree in midtown Manhattan, he couldn’t be charged with a crime until he was no longer president.

Without enumerating President Trump’s rhetorical offenses and deviations from cultural and political norms, how does he get away with so much? Why doesn’t he lose his base of his electoral support or any of his senatorial allies?

It’s because of framing and branding. Trump isn’t held accountable because he has never been held accountable. He has never been held accountable because he has never allowed himself to be held accountable.

Hitler believed that, in a confrontation, the combatant with the strongest inner will had an innate advantage over his opponent. Audacity, tenacity and the ability to keep your nerve under pressure were essential character traits, especially for an individual up against stronger adversaries. Trump never read “Mein Kampf” but he follows the Führer’s prescription for success. He never apologizes. He never admits fault or defeat. He lies his failures into fake successes, reframing history into a narrative that he prefers. It’s all attitude: because I am me, I can do no wrong.

I’m not a billionaire real estate grifter turned billionaire presidential con man.

But I get this.

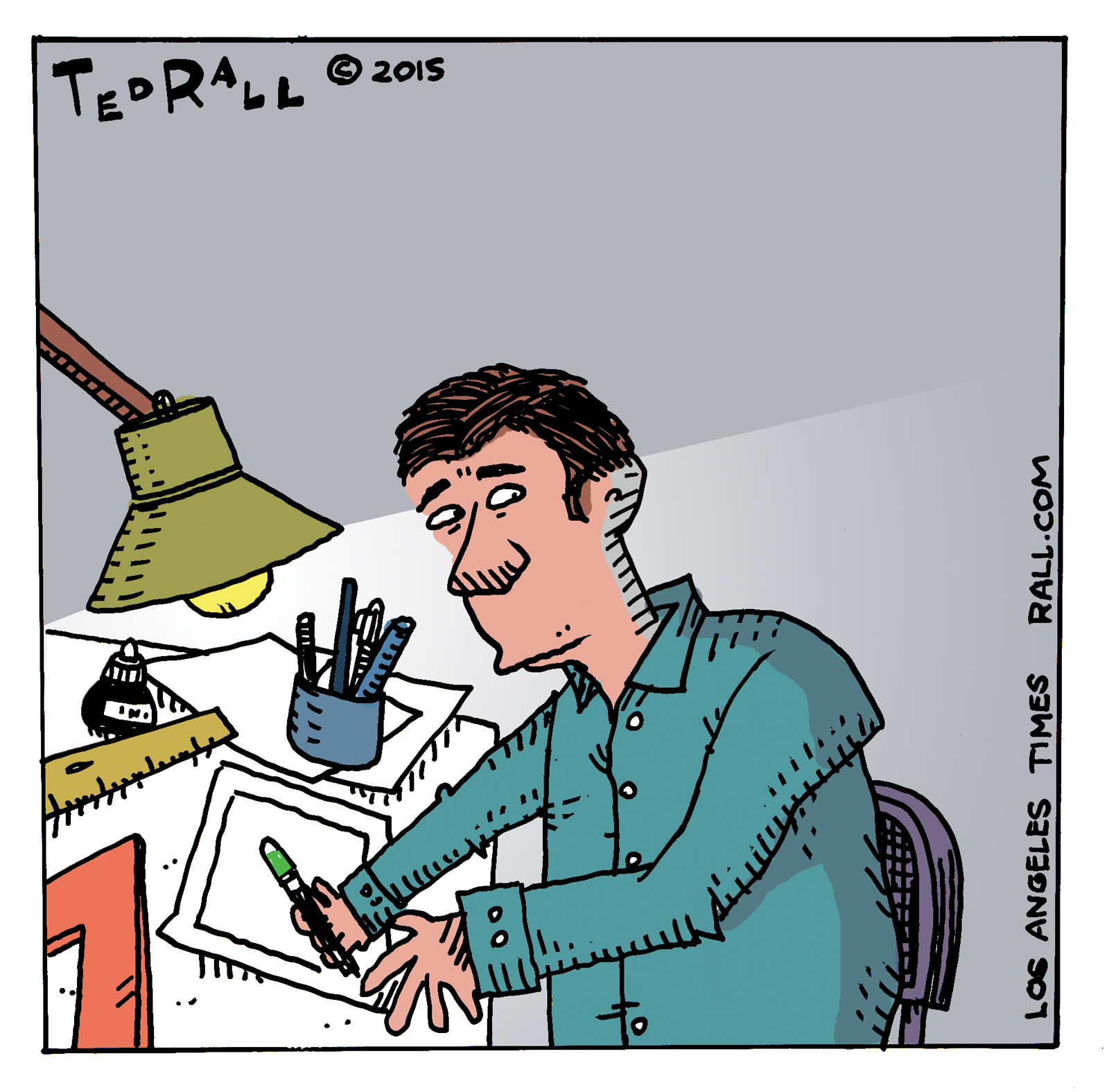

When I began my career as an editorial cartoonist, I staked out ideological territory far to the left of my older, established colleagues, most of whom were ordinary Democrats. In the alternative weeklies, other cartoonists were as far left as me. But they weren’t syndicated. I went after mainstream daily newspapers. My first two syndication clients were the Philadelphia Daily News and the Los Angeles Times.

My status as an ideological outlier reduced the number of newspapers willing to publish my work. But the editors who did take a chance on me knew what they were getting and so were able to defend me against ideological attacks. Once they saw that braver papers were publishing my cartoons, moderate publications picked them up too.

Despite being an unabashed, unrepentant leftist, I became the most reprinted cartoonist in The New York Times. Secretly, many of the “Democratic” cartoonists were as left as me. They were jealous: how had I gotten away with wearing my politics on my sleeve in such bland outlets as The Des Moines Register and The Atlanta Constitution?

First, I was willing to take some heat. I accepted that I would get fewer clients and thus less income. I insisted on drawing the work I wanted to do, never watering down my politics. If everyone rejected me, that was fine. Better not to appear in print than to do wimpy work. And in the long run, I was better off. There have been rough patches. But progressives have taken over the Democratic Party. I’m one of the few pundits the left can trust for a simple reason: unlike Bill Maher and Arianna Huffington, I have always been one of them, regardless of prevailing winds.

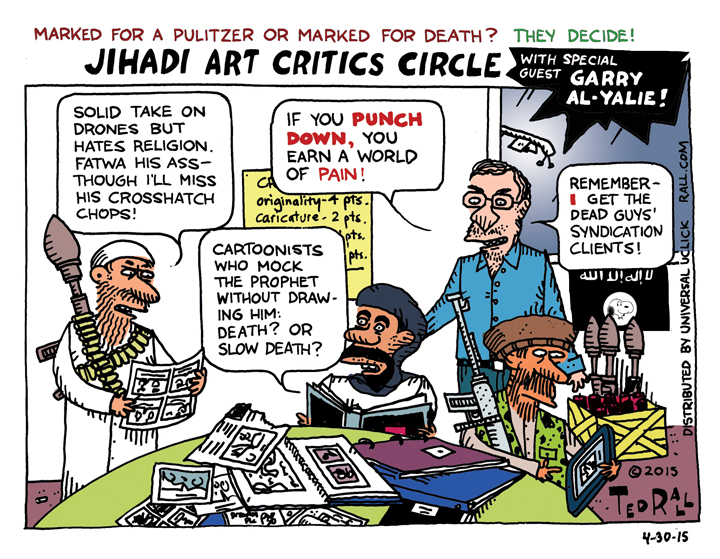

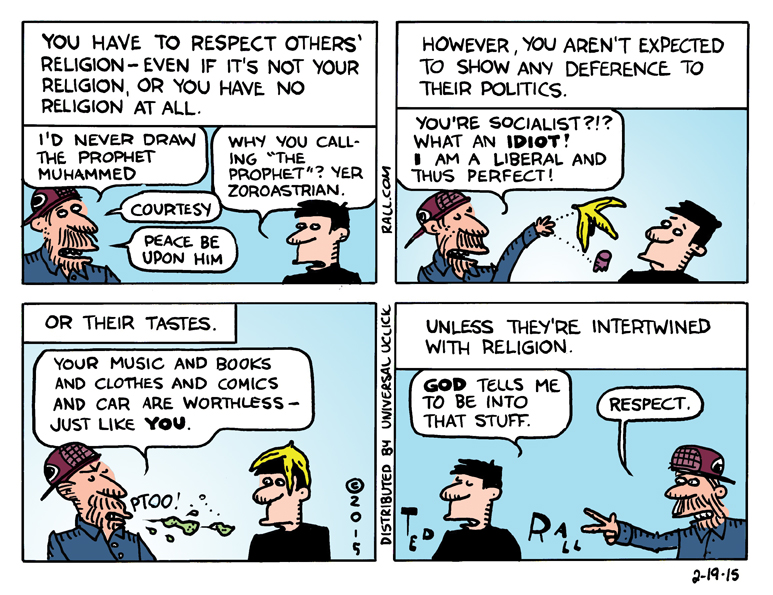

Second, I developed an unusual drawing style. When I started out most editorial cartoonists mimicked two icons of the 1960s and 1970s, Pat Oliphant and Jeff MacNelly. The “OliNelly” house style of American political cartooning was busy, reliant on caricature and crosshatching. Daily newspaper staffers drew single-panel cartoons structured around metaphors, labels and hoary symbols like Uncle Sam, the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant.

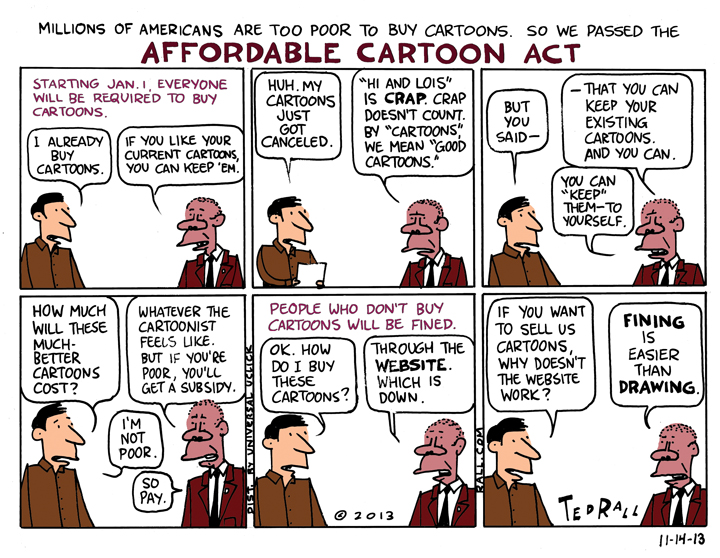

I did everything the opposite. I drew multiple panels, wrote straightforward scripts inspired by comic strips. My drawing style stripped down to a brutally simple abstract look in which most characters looked almost identical. No metaphors—you didn’t need to learn how to read a Ted Rall cartoon. They weren’t as pretty as MacNelly’s. The chairman of the Pulitzer committee, whose death I shall toast, denied me the prize because I didn’t “draw like a normal editorial cartoonist.” But you knew my stuff wasn’t by anyone else. Branding.

I created space for myself ideologically and stylistically. So I got away with—still get away with—more than many of my peers.

Finally, I learned to never apologize.

Most of the time when a cartoonist apologizes for causing offense, they don’t mean it. Their editors, themselves feeling the heat from an avalanche of letters-to-the-editor and social media opprobrium, force them to say they’re sorry. This I will not do. It’s too undignified.

Sometimes cartoonists really do screw up. In one particular cartoon I took aim at the president and instead wound up wounding a group of disadvantaged people. So I acted like a human being: I apologized.

What a mistake! Papers that had stuck with me through previous controversies abandoned me, canceling my work. The group I’d apologized to proclaimed itself satisfied and appealed to the quislings to reconsider, in vain. I learned my lesson. Never apologize, especially when you’re wrong. Americans forgive evil, never weakness.

With his far longer reach, influence and experience than yours truly, Donald Trump has figured out how to carve out room for himself to run off at the mouth, offend protected groups and defy cherished traditions. No one can make him stop. No one but him. And no one can make him say he’s sorry.

(Ted Rall (Twitter: @tedrall), the political cartoonist, columnist and graphic novelist, is the author of “Francis: The People’s Pope.” You can support Ted’s hard-hitting political cartoons and columns and see his work first by sponsoring his work on Patreon.)